Bonds & Interest Rates

It’s a big club…. and you ain’t in it.”

It’s a big club…. and you ain’t in it.”

— George Carlin

It must be a byproduct of the government-controlled education system; people still think they live in a free country with a representative democracy. It’s anything but.

Voting, elections, etc. are all just illusions to make people think that they have some influence in society.

A tiny elite orchestrates the whole system. And one of the most influential conductors is the Federal Reserve, a body soon to be chaired by Janet Yellen. Her confirmation process begins today.

Since most people have no idea how central banking really works, her confirmation hearing today is just a footnote.

Even people who are otherwise financially sophisticated simply trust that the men behind the curtain know what they’re doing.

This is quite strange when you consider that central bankers have nearly total control over the economy.

In their sole discretion, they are able to set interest rates, conjure money out of thin air, finance trillion-dollar government deficits, bail out commercial banks, etc.

And through these tools, they have the power to manipulate the prices of just about anything, from the Google stock to real estate in Thailand to turnips in Sri Lanka.

For the last several years, the US central bank has set the example for the rest of the world in aggressively using their policy tools.

Most significantly, they have unabashedly printed money in unprecedented quantities. And this has not been without consequence.

For some, the effects have been beneficial.

Rapid expansion of the money supply has pushed asset prices up all over the world. Stocks. Bonds. Many commodities. US Farmland. Artwork. Fine wines. Just about every asset class imaginable is near its all-time high.

People who are already wealthy have the available funds to invest in these markets. So their wealth has grown even more– exponentially.

The middle class, on the other hand, is experiencing an entirely different effect of money printing– retail price inflation.

And anyone who has been to a gas station, airport, university, doctor’s office, grocery store, etc. over the last few years understands this phenomenon very well.

A typical middle class family has little excess cash to invest after paying for rapidly increasing living expenses. Food. Fuel. Mortgage. Insurance. Etc.

And whatever wages or savings they have are being eaten away by inflation. So while the wealthy are getting wealthier exponentially, the middle class is actually getting poorer.

This explains why the wealth gap in the Land of the Free is the largest since 1929 at the start of the Great Depression.

Central bankers are responsible for much of this. In conjuring money out of thin air, they are benefitting one segment of society at the expense of another.

And with Janet Yellen soon chairing the Fed, very little will change.

Yellen has made it clear that she will continue to print unlimited quantities of money despite overwhelming data that such actions are ineffective and destructive for the the majority of the population.

Kyle Reese from the first Terminator movie sums up the consequences for the middle class rather succinctly:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zu0rP2VWLWw

I’m an international investor, entrepreneur, permanent traveler, free man. Thisfree daily e-letter is about using the experiences from my life and travels to help you achieve more freedom.

Over the last few years I’ve traveled to over 100 countries, met with a President and several diplomats, briefed sovereign fund managers, flown an aerobatic stunt plane, started several companies, hitchhiked in Bogota, taken a train across the orient, lectured on entrepreneurship in Eastern Europe, and personally provided venture capital to new start-ups.

I’m a student of the world, and I believe that travel is the greatest teacher. My knowledge is practical, and hopefully of significant use to you. Off the top of my head I could quote you the price of beachfront property in Croatia, where to bank in Dubai, the best place to store gold in Singapore, which cities in Mexico are the safest, which hospitals in Asia are the most cost effective, and how to find condo foreclosure listings in Panama.

I believe that in order to achieve true freedom, you have to be able to make money, control your time, and eliminate the mindset that you are subject to a corrupt government that is bent on degrading your personal liberty.

As H.L. Mencken opined, “The most dangerous man to any government is the man who is able to think things out for himself, without regard to the prevailing superstitions and taboos. Almost inevitably he comes to the conclusion that the government he lives under is dishonest, insane, and intolerable.”

As H.L. Mencken opined, “The most dangerous man to any government is the man who is able to think things out for himself, without regard to the prevailing superstitions and taboos. Almost inevitably he comes to the conclusion that the government he lives under is dishonest, insane, and intolerable.”

It is no wonder that, according to a Gallup Poll conducted in early October, a record-low 14% of Americans thought that the country was headed in the right direction, down from 30% in September. That’s the biggest single-month drop in the poll since the shutdown of 1990. Some 78% think the country is on the wrong track.

Some readers will, of course, ask what this expose about the political future has to do with investments. It has nothing to do with what the stock market will do tomorrow, the day after tomorrow, or in the next three months. But it has a lot to do with the future of the US (and other Western democracies where socio-political conditions are hardly any better).

I have written about the consequences of a dysfunctional political system elsewhere. In the May 2011 I explained how expansionary monetary policies had favored what Joseph Stiglitz called “the elite” at the expense of ordinary people by increasing the wealth and income of the “one percent” far more than that of the majority of the American people.

I also quoted at the time Alexander Fraser Tytler (1747–1813), who opined as follows: “A democracy cannot exist as a permanent form of government. It can only exist until voters discover that they can vote themselves largesse from the Public Treasury. From that moment on, the majority always votes for the candidates promising the most benefits from the Public Treasury with the result that a democracy always collapses over loose fiscal policy, always followed by dictatorship” (emphasis added).

Later, Alexis de Tocqueville observed: “The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public’s money.”

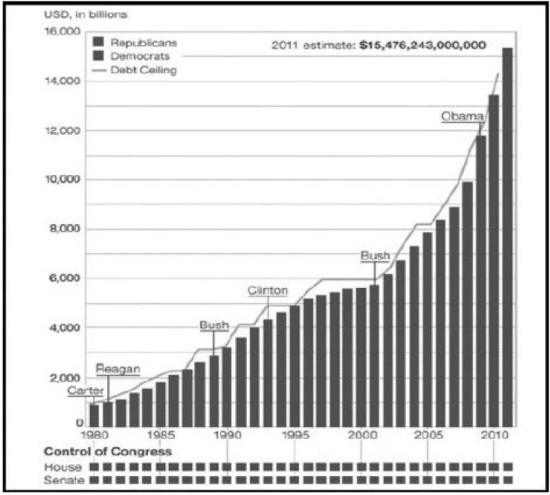

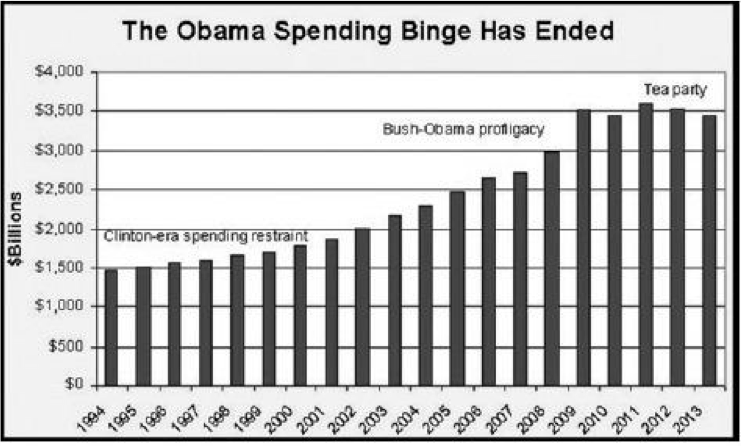

To be fair to Mr. Obama, the government debt under his administration has expanded at a much slower pace in percentage terms than under the Reagan administration and the two Bush geniuses. In fact, as much as I hate to say this, Mr. Obama has been (or been forced to be) a fiscal conservative.

However, what 18th and 19th-century economists and social observers failed to observe is that democracies can also collapse over loose monetary policies. And in this respect, under the Obama administration, the Fed’s balance sheet has exploded. John Maynard Keynes got it 100% right when he wrote:

By a continuing process of inflation, Governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some… Those to whom the system brings windfalls… become “profiteers” who are the object of the hatred… The process of wealth getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery… Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose [emphasis added].

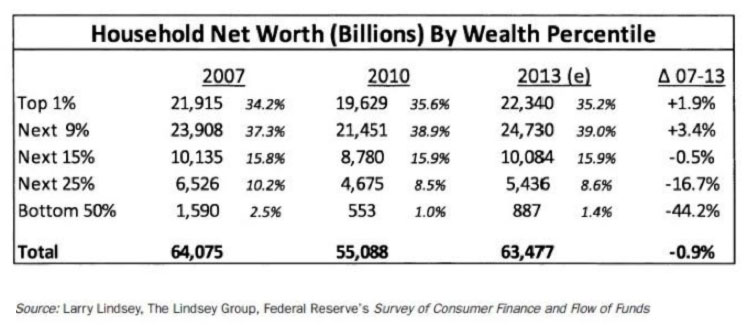

The Fed takes great pride in the fact that US household wealth has now exceeded the 2007 high. However, I was pleasantly surprised when I recently attended a presentation by Larry Lindsey, at my friend Gary Bahre’s New Hampshire estate. He unmistakably showed, based on the Fed’s own Survey of Consumer Finance and Flow of Funds, that the recovery in household wealth has been extremely uneven.

Readers should focus on the last column of Table 1, which depicts the change in household wealth between 2007 and 2013 by wealth percentile. As can be seen, the bottom 50% of the population is still down more than 40% in terms of their “wealth” from the 2007 high. (Lindsey is a rather level-headed former Member of the Board of the Governors of the Federal Reserve System, in which capacity he served between 1991 and 1997.)

Besides the uneven recovery of household wealth among different wealth groups, a closer look at consumer credit, which is now at a record level, is also revealing. Furthermore, consumer credit as a percentage of disposable personal income is almost at the pre-crisis high. But what I found most interesting is how different income and wealth groups adjusted their outstanding total debt (including consumer credit, mortgage debt, etc.) following the crisis.

Larry Lindsey showed us a table — again based on the Fed’s own Survey of Consumer Finance and Flow of Funds data — which depicts total debt increases and decreases (in US$ billions) among these different income and wealth groups. I find it remarkable that the lower 40% of income recipients and the lower 50% of wealth owners actually increased their debts meaningfully post-2007. In other words, approximately 50% of Americans in the lower income and wealth groups who are both voters and consumers would seem to be more indebted than ever. A fair assumption is also that these people form the majority of the government’s social benefits recipients.

Now, since these lower income and wealth groups increased their debts post-2007 and enjoyed higher social benefits, they were also to some extent supporting the economy and corporate profits. But what about the future?

Entitlements are unlikely to expand much further as a percentage of GDP, and these lower-income recipients’ higher debts are likely to become a headwind for consumer spending. Simply put, in my opinion, it is most unlikely that US economic growth will surprise on the upside in the next few years.

It is more likely there will be negative surprises.

Regards,

Marc Faber

for The Daily Reckoning

[For Retirees: If you’re like many Americans who want to retire (or have already) you’re worried about running out of the money you’ve worked your entire adult life for… just when you need it most. And as Dr. Faber pointed out, it’s harder for average Americans to grow their wealth now more than ever before.

But luckily for you, we’ve recently uncovered an incredibly effective strategy that could allow you to make as much money as you need, within a month. We know, it sounds unlikely but the proof is right here. The strategy has been popular so far. In fact, we have under 200 spots left to learn about it. We don’t want you to miss out, so click here for details on this opportunity.]

“We went on a bond-buying spree that was supposed to help Main Street. Instead, it was a feast for Wall Street.”

By ANDREW HUSZAR, in charge of the Federal Reserve’s $1.25 trillion agency mortgage-backed security purchase program (QE 1) in 2009-2010.

Five years ago this month, on Black Friday, the Fed launched an unprecedented shopping spree. By that point in the financial crisis, Congress had already passed legislation, the Troubled Asset Relief Program, to halt the U.S. banking system’s free fall. Beyond Wall Street, though, the economic pain was still soaring. In the last three months of 2008 alone, almost two million Americans would lose their jobs.

The Fed said it wanted to help—through a new program of massive bond purchases. There were secondary goals, but Chairman Ben Bernanke made clear that the Fed’s central motivation was to “affect credit conditions for households and businesses”: to drive down the cost of credit so that more Americans hurting from the tanking economy could use it to weather the downturn. For this reason, he originally called the initiative “credit easing.”

My part of the story began a few months later. Having been at the Fed for seven years, until early 2008, I was working on Wall Street in spring 2009 when I got an unexpected phone call. Would I come back to work on the Fed’s trading floor? The job: managing what was at the heart of QE’s bond-buying spree—a wild attempt to buy $1.25 trillion in mortgage bonds in 12 months. Incredibly, the Fed was calling to ask if I wanted to quarterback the largest economic stimulus in U.S. history.

This was a dream job, but I hesitated. And it wasn’t just nervousness about taking on such responsibility. I had left the Fed out of frustration, having witnessed the institution deferring more and more to Wall Street. Independence is at the heart of any central bank’s credibility, and I had come to believe that the Fed’s independence was eroding. Senior Fed officials, though, were publicly acknowledging mistakes and several of those officials emphasized to me how committed they were to a major Wall Street revamp. I could also see that they desperately needed reinforcements. I took a leap of faith.

In its almost 100-year history, the Fed had never bought one mortgage bond. Now my program was buying so many each day through active, unscripted trading that we constantly risked driving bond prices too high and crashing global confidence in key financial markets. We were working feverishly to preserve the impression that the Fed knew what it was doing.

It wasn’t long before my old doubts resurfaced. Despite the Fed’s rhetoric, my program wasn’t helping to make credit any more accessible for the average American. The banks were only issuing fewer and fewer loans. More insidiously, whatever credit they were extending wasn’t getting much cheaper. QE may have been driving down the wholesale cost for banks to make loans, but Wall Street was pocketing most of the extra cash.

From the trenches, several other Fed managers also began voicing the concern that QE wasn’t working as planned. Our warnings fell on deaf ears. In the past, Fed leaders—even if they ultimately erred—would have worried obsessively about the costs versus the benefits of any major initiative. Now the only obsession seemed to be with the newest survey of financial-market expectations or the latest in-person feedback from Wall Street’s leading bankers and hedge-fund managers. Sorry, U.S. taxpayer.

Trading for the first round of QE ended on March 31, 2010. The final results confirmed that, while there had been only trivial relief for Main Street, the U.S. central bank’s bond purchases had been an absolute coup for Wall Street. The banks hadn’t just benefited from the lower cost of making loans. They’d also enjoyed huge capital gains on the rising values of their securities holdings and fat commissions from brokering most of the Fed’s QE transactions. Wall Street had experienced its most profitable year ever in 2009, and 2010 was starting off in much the same way.

You’d think the Fed would have finally stopped to question the wisdom of QE. Think again. Only a few months later—after a 14% drop in the U.S. stock market and renewed weakening in the banking sector—the Fed announced a new round of bond buying: QE2. Germany’s finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, immediately called the decision “clueless.”

That was when I realized the Fed had lost any remaining ability to think independently from Wall Street. Demoralized, I returned to the private sector.

Where are we today? The Fed keeps buying roughly $85 billion in bonds a month, chronically delaying so much as a minor QE taper. Over five years, its bond purchases have come to more than $4 trillion. Amazingly, in a supposedly free-market nation, QE has become the largest financial-markets intervention by any government in world history.

And the impact? Even by the Fed’s sunniest calculations, aggressive QE over five years has generated only a few percentage points of U.S. growth. By contrast, experts outside the Fed, such as Mohammed El Erian at the Pimco investment firm, suggest that the Fed may have created and spent over $4 trillion for a total return of as little as 0.25% of GDP (i.e., a mere $40 billion bump in U.S. economic output). Both of those estimates indicate that QE isn’t really working.

Unless you’re Wall Street. Having racked up hundreds of billions of dollars in opaque Fed subsidies, U.S. banks have seen their collective stock price triple since March 2009. The biggest ones have only become more of a cartel: 0.2% of them now control more than 70% of the U.S. bank assets.

As for the rest of America, good luck. Because QE was relentlessly pumping money into the financial markets during the past five years, it killed the urgency for Washington to confront a real crisis: that of a structurally unsound U.S. economy. Yes, those financial markets have rallied spectacularly, breathing much-needed life back into 401(k)s, but for how long? Experts like Larry Fink at the BlackRock investment firm are suggesting that conditions are again “bubble-like.” Meanwhile, the country remains overly dependent on Wall Street to drive economic growth.

Even when acknowledging QE’s shortcomings, Chairman Bernanke argues that some action by the Fed is better than none (a position that his likely successor, Fed Vice Chairwoman Janet Yellen, also embraces). The implication is that the Fed is dutifully compensating for the rest of Washington’s dysfunction. But the Fed is at the center of that dysfunction. Case in point: It has allowed QE to become Wall Street’s new “too big to fail” policy.

This column appeared in the Wall Street Journal on November 11, 2013.”

“It will end badly” Look at China, its credit as a percent of the economy has increased by 50 percent in the last 4-1/2 years. This is the fastest credit growth you can imagine in the whole of Asia,”

“It will end badly” Look at China, its credit as a percent of the economy has increased by 50 percent in the last 4-1/2 years. This is the fastest credit growth you can imagine in the whole of Asia,”

“It will end badly and the question is whether we will have a minor economic crisis and then huge money printing or get into an inflationary spiral first,”

“Why are so many product prices in Singapore and Hong Kong more expensive than in the U.S.? It’s because when you have asset inflation and high property prices, shops have to pay higher rents, so they charge more for their products. So asset inflation can flow into consumer inflation,”

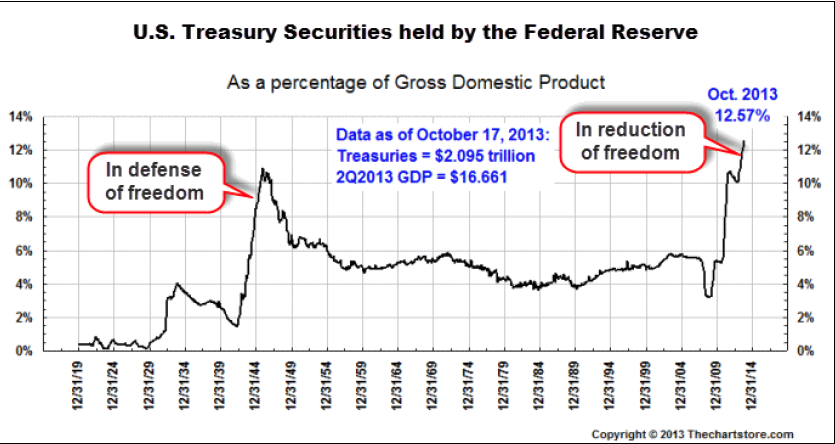

– World War II was prosecuted in the defense of freedom.

– Extraordinary funding measures were justifiable.

– The increase was from 1.8% to 11%, or when rounded 10 points.

– Freedom was restored where possible.

– It has since been a challenge to ambitious governments.

– The recent increase has been from 3.3% to 12.6%, which rounds out to 9 points.

– Essentially, this has been to fund the expansion of the state for the state itself.

– Ironically, this has been part of a relentless attempt to extinguish freedom.

From Bob Hoye: By way of “proof of the pudding”, we will provide you with a FREE TRIAL SUBSCRIPTION.

Opinions in this report are solely those of the author. The information herein was obtained from various sources; however we do not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. This research report is prepared for general circulation and is circulated for general information only. It does not have regard to the specific investment objectives, financial situation and the particular needs regarding the appropriateness of investing in any securities or investment strategies discussed or recommended in this report and should understand that statements regarding future prospects may not be realized.

Investors should note that income from such securities, if any, may fluctuate and that each security’s price or value may rise or fall. Accordingly, investors may receive back less than originally invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance. Neither the information nor any opinion expressed constitutes an offer to buy or sell any securities or options or futures contracts. Foreign currency rates of exchange may adversely affect the value, price or income of any security or related investment mentioned in this report. In addition, investors in securities such as ADRs, whose values are influenced by the currency of the underlying security, effectively assume currency risk. Moreover, from time to time, members of the Institutional Advisors team may be long or short positions discussed in our publications.

BOB HOYE, INSTITUTIONAL ADVISORS EMAIL bhoye.institutionaladvisors@telus.net WEBSITE www.institutionaladvisors.com