Bonds & Interest Rates

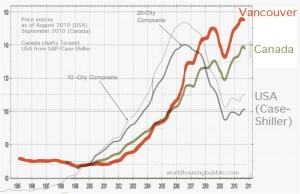

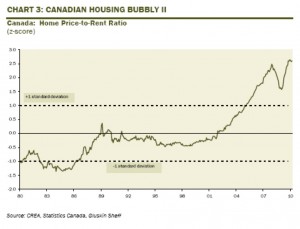

Does Canada have a housing bubble? It is a common question these days and based on some simple analysis of aggregate data on current prices versus long-term historical averages, rents and income the answer for certain markets would appear to be yes. However, there is considerable variation by local market as to the degree by which houses have deviated from long-term averages – a few more years of ZIRP by the Bank of Canada and that remains to be seen.

I would put limited credence on the metric most favoured by housing cheerleaders – affordability as measured by mortgage rates – as interest rates are at historic lows and ultimately a house is a long-term consumption good and long-term income levels must dictate prices.

House Prices versus Income (click on charts for larger version)

House Prices versus Rental Costs

House Prices versus Historical Averages

Of course some markets are better than others, but certainly the key, large markets seem stretched as can be seen in recent research by Demograhia:

“Historically, the Median Multiple has been remarkably similar in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States, with median house prices having generally been from 2.0 to 3.0 times median household incomes (historical data has not been identified for Hong Kong), with 3.0 being the outer bound of affordability. This affordability relationship continues in many housing markets of the United States and Canada. However, the Median Multiple has escalated sharply in the past decade in Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom and in some markets of Canada and the United States.

Housing in Canada is moderately unaffordable with a Median Multiple of 4.6 in major metropolitan markets and 3.4 overall. Housing was generally affordable in Canada as late as 2000. In the early years of the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, Canada was generally the most affordable nation. However, this year, Canada ranks third, behind the United States and Ireland.

Among major markets, four were moderately unaffordable and two were severely unaffordable. Among all markets, 9 were affordable, 17 were moderately unaffordable, 3 were seriously unaffordable and 6 were severely unaffordable. The four most unaffordable metropolitan markets were in British Columbia (Table 7).

Edmonton was the most affordable major market, with a Median Multiple of 3.5, while Ottawa-Gatineau had a Median Multiple of 3.7. Both of these markets were rated moderately unaffordable.

Canada’s most affordable markets were Windsor (ON) at 2.2, Fredericton (NB) at 2.4, Moncton (NB) at 2.5. Other affordable markets were Saint John (NB) and Thunder Bay (ON) at 2.6. Yellowknife (NWT) and Charlottetown (PEI) at 2.9 and Saguenay (QC) at 3.0 and Trois-Rivieres (QC) at 3.0.

Vancouver, which like Sydney has largely prohibited housing development on the urban fringe for decades, experienced a significant deterioration, with housing reaching a Median Multiple of 10.6, replacing Sydney as the second most unaffordable market in the Survey, following Hong Kong. Toronto was also severely unaffordable, at 5.5, a deterioration of 40 percent in housing affordability since 2004, as that metropolitan area’s “smart growth” program has taken effect. Montreal has been one of the worst performers in housing affordability, over the years of the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, with a Median Multiple of 5.1, up nearly 60 percent from 2004, at the same time as the land for development has been severely limited by an inflexible approach to agricultural zoning. Smaller British Columbia markets Abbotsford (7.0), Victoria (6.6) and Kelowna (6.6) were also severely unaffordable.”

House prices are highly mean reverting to median income and it is on that metric that most markets seem stretched. The timing and path of trend changes are always challenging to predict – are we facing an imminent and sharp price adjustment or a long, drawn out malaise. Perhaps the relentless upward march will continue?

Stephen Johnston

We have the money printing today which we did not have before and so it is very difficult to predict because it is always a political decision. Conventional wisdom went wrong because it has been brainwashed by the media and the policy makers. What’s happened is not the failure of the free market, but the failure of the interventionists with monetary fiscal policies and regulation.

All I can say is if you look at history the most powerful people were usually in the end killed or hanged or crucified, and the central bankers today are the most powerful people. So you can imagine what I am thinking about the central banks, and what will eventually happen to their leading employees.

More below in an interview with Australia Financial Radio:

About Marc Faber:

Dr Marc Faber was born in Zurich, Switzerland. He went to school in Geneva and Zurich and finished high school with the Matura. He studied Economics at the University of Zurich and, at the age of 24, obtained a PhD in Economics magna cum laude. Between 1970 and 1978, Dr Faber worked for White Weld & Company Limited in New York, Zurich and Hong Kong. Since 1973, he has lived in Hong Kong. From 1978 to February 1990, he was the Managing Director of Drexel Burnham Lambert (HK) Ltd. In June 1990, he set up his own business, which acts as an investment advisor and fund manager. You can read and watch more at his MARC FABER BLOG which tracks Faber’s Investment Strategy , Market analysis & Outlook.

- The United States government will default.

- The United States government will not default.

I hold the first position. John T. Harvey holds the second. He wrote a piece for Forbes defending his position: “It Is Impossible For The US To Default“.

I regard this as the most fundamental economic issue facing the U.S. government. I regard it as the most fundamental economic issue facing Americans under age 60.

Mr. Harvey begins.

With so many economic, political, and social problems facing us today, there is little point in focusing attention on something that is not one. The false fear of which I speak is the chance of US debt default. There is no need to speculate on what that likelihood is, I can give you the exact number: there is 0% chance that the US will be forced to default on the debt.

That is the kind of forthrightness that I appreciate. Here is my response. With so many economic, political, and social problems facing us today, it is crucial that we focus attention on something that is both catastrophic and inescapable. The fear of which I speak is the chance of U.S. debt default. There is no need to speculate on what that likelihood is, I can give you the exact number: there is 100% chance that the U.S. will be forced to default on the debt.

UNFUNDED LIABILITIES

Why do I believe this? Because I believe in the analysis supplied by Professor Lawrence Kotlikoff of Boston University. Each year, he analyzes the statistics produced by the Congressional Budget Office on the present value – not future value – of the unfunded liabilities of the U.S. government. The latest figures are up by $11 trillion over the last year. The figure today is $222 trillion.

This means that the government needs $222 trillion to invest in private capital markets that will pay about 5% per year for the next 75 years.

Problem: the world’s capital markets are just about $222 trillion. Then there are the unfunded liabilities of all other Western nations. These total at least what the U.S. does, and probably far more, since the welfare state’s promises are more comprehensive outside the USA.

Conclusion: they will all default.

Mr. Harvey thinks that the U.S. government could choose to default, but it won’t.

We could choose to do so, just as a person trapped in a warehouse full of food could choose to starve, but we could never be forced to. This is not a theory or conjecture, it is cold, hard fact. The reason the US could never be forced to default is that every single bit of the debt is owed in the currency that we and only we can issue: dollars. Unlike Greece, we don’t have to try to earn foreign exchange via exports or beg for better terms. There is simply no level of debt we could not repay with a keystroke.

There are a lot of people inside the camp of the gold bugs who also believe this. They are probably wrong. They are wrong for the same reason why Mr. Harvey is wrong. They do not understand Ludwig von Mises.

MISES ON THE CRACK-UP BOOM

Mises was a senior advisor to the equivalent of the Austrian Chamber of Commerce after World War I. He understood monetary theory. His book on money, The Theory of Money and Credit, had been published in 1912, two years before the war broke out.

In the post-War edition of his book, he wrote of the process of the hyperinflationary breakdown of a currency. He made it clear that such a currency is short-lived. People shift to rival currencies.

The emancipation of commerce from a money which is proving more and more useless in this way begins with the expulsion of the money from hoards. People begin at first to hoard other money instead so as to have marketable goods at their disposal for unforeseen future needs – perhaps precious-metal money and foreign notes, and sometimes also domestic notes of other kinds which have a higher value because they cannot be increased by the State ‘(e.g.the Romanoff rouble in Russia or the ‘blue’ money of communist Hungary); then ingots, precious stones, and pearls; even pictures, other objects of art, and postage stamps. A further step is the adoption of foreign currency or metallic money (i.e. for all practical purposes, gold) in credit transactions. Finally, when the domestic currency ceases to be used in retail trade, wages as well have to be paid in some other way than in pieces of paper which are then no longer good for anything. The collapse of an inflation policy carried to its extreme – as in the United States in 1781 and in France in 1796 does not destroy the monetary system, but only the credit money or fiat money of the State that has overestimated the effectiveness of its own policy. The collapse emancipates commerce from etatism and establishes metallic money again (pp. 229-30).

In 1949, his book Human Actionappeared. In it, he discussed hyperinflation. He called this phase of the business cycle the crack-up boom.

The characteristic mark of the phenomenon is that the increase in the quantity of money causes a fall in the demand for money. The tendency toward a fall in purchasing power as generated by the increased supply of money is intensified by the general propensity to restrict cash holdings which it brings about. Eventually a point is reached where the prices at which people would be prepared to part with “real” goods discount to such an extent the expected progress in the fall of purchasing power that nobody has a sufficient amount of cash at hand to pay them. The monetary system breaks down; all transactions in the money concerned cease; a panic makes its purchasing power vanish altogether. People return either to barter or to the use of another kind of money (p. 424).

Later in the book, Mises discussed the policy of devaluation: the expansion of the domestic money supply in a fruitless attempt to reduce the international value of the currency unit.

If the government does not care how far foreign exchange rates may rise, it can for some time continue to cling to credit expansion. But one day the crack-up boom will annihilate its monetary system. On the other hand, if the authority wants to avoid the necessity of devaluing again and again at an accelerated pace, it must arrange its domestic credit policy in such a way as not to outrun in credit expansion the other countries against which it wants to keep its domestic currency at par (p. 791).Mt. Harvey has described just such a policy. He concluded that the United States government can never go bankrupt. It can print its way out of every obligation.

No, it can’t.

HYPERINFLATIONARY COLLAPSE

The expansion of the monetary base can go on until such time as commercial banks monetize all of the reserves on their books. Prices then rise to such levels that transactions no longer take place in the official currency unit. The division of labor contracts. The output of capital and labor falls. At some point, people adopt other currency units. They no longer cooperate with each other by means of the hyperinflated currency.

Professor Steve Hanke has co-authored an article on the worst 56 hypernflations. He discovered that most of these in industrial nations were over in a couple of years. The crack-up boom ended them.

No nation can long pursue a policy of hyperinflation. It destroys the currency and destroys the division of labor. The result is starvation. The policy of hyperinflation ends before this phase. Members of society shift to other forms of money.

This is why the policy of hyperinflation is useless in dealing with the 75-year obligations of the federal government to support old people through Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and federal pensions. These obligations are inter-generational. Hyperinflation lasts for months, not decades. When the government ends its policy of hyperinflation, it finds that it is still saddled with these obligations.

If the Federal Reserve resorts to hyperinflation, its retirement portfolio will reach zero value unless it shifts to foreign currencies, gold, or other hyperinflation hedges. It will publicly announce that the U.S. dollar is a failed currency, as manipulated by the FED.

If it refuses, then it will oversee Great Depression 2, monetary deflation, and the contraction of the division of labor. The U.S. government will go bankrupt.

If Congress nationalizes the FED, then it will pursue hyperinflation. The crack-up boom will end the experiment.

At that point, all of the obligations to retirees will still remain. But the government will not have the money to pay them. The $222 trillion of present valued unfunded liabilities will still remain unfunded.

The government’s obligations are inter-generational. Hyperinflation is not. The latter in no fundamental way reduces the former.

This means that the government will default. This is 100% guaranteed.

CITING ECONOMIC EXPERTS

Mr. Harvey cites the experts. “Don’t take my word for it. Here are just a few folks from across the political spectrum and in different walks of life saying the same thing.” Then he gives a series of quotations from these men: Alan Greenspan, Peter Zeihan, Erwan Mahe, Mike Norman, Monty Agarwal, L. Randall Wray. Other than Mr. Greenspan, I had heard of none of them. He concludes:

Mind you, that doesn’t mean there might not be other economic or political consequences. Inflation and currency depreciation, for example, are possibilities.

Yes, they surely are, since they are the same thing. But they do not solve the problem of the inevitable default. They merely add to the misery before the default.

Indeed, we have seen neither hide nor hair of inflation or high interest rates during the current run up of the debt. It is critical to bear in mind, too, that these deficits are not a result of the government trying to buy something it cannot otherwise afford (as would be the case for you or me). Rather, they are setting out to generate sufficient demand for goods and services to employ all those willing to work (that said, not every kind of government spending does this effectively, but that’s a different question). As there is no limit to how much debt we can successfully carry, we should be aggressively pursuing the latter goal rather than talking about being “fiscally responsible.” There is nothing responsible about leaving over 12 million Americans out of work.

CONCLUSION

This appeared in Forbes. The article cited a list of supposed experts, with Alan Greenspan at the head of the list. Somehow, the author expects us to take his argument seriously. We are also supposed to take his cited experts seriously, beginning with Alan Greenspan. We are supposed to imagine that debts are forever, that they need not be repaid, that credit is eternal, that the Baby boomers are not retiring by the millions, that digits can overcome economic theory, that Medicare is solvent, that Social Security is solvent, and that hyperinflation is always available as a way for the government not to default.

The nation is run by people who share his views. So is every Western nation.

This is a very good reason to prepare for a catastrophe, if we are lucky, or possibly several: (1) mass inflation, stabilization, deflation, depression, and government default, or (2) hyperinflation followed by a default. Take your pick.

Gary North [send him mail ] is the author of Mises on Money . Visit http://www.garynorth.com . He is also the author of a free 20-volume series, An Economic Commentary on the Bible .

© 2012 Copyright Gary North / LewRockwell.com – All Rights Reserved

Disclaimer: The above is a matter of opinion provided for general information purposes only and is not intended as investment advice. Information and analysis above are derived from sources and utilising methods believed to be reliable, but we cannot accept responsibility for any losses you may incur as a result of this analysis. Individuals should consult with their personal financial advisors.

Bond investors don’t have anything good to look forward to anymore.

Up until last week, the bond market could look forward to a third round of quantitative easing (QE3) – aka money printing – and the renewed promise of low interest rates. But with the Fed announcing QE3 would last as long as necessary, bond investors can no longer look forward to QE4 or QE5. And that’s bad news for bond prices.

Let me explain…

Quantitative easing programs haven’t lowered interest rates. Rather, as I explained in July, it was the anticipation of QE that lowered rates. Just look at this chart of the 10-year Treasury yield…

The numbers on the chart indicate the QE timeline.

The first point is when the Fed began its first QE program. Notice how interest rates fell sharply – as bond prices rallied – in anticipation of the Fed’s buying binge. Rates started to rise as soon as the Fed started buying bonds.

At Point 2, the Fed increased the amount of QE from $600 billion to $1.25 trillion… Yet interest rates continued higher.

By the time the first QE program ended in April 2010 (Point 3), the 10-year yield had risen from 2.1% to nearly 4%. Interest rates were right back up to where they were before the Fed got involved in the market. The gain in bond prices occurred in anticipation of the first QE program, not as a result of it.

Almost as soon as QE1 ended, bond investors started looking forward to QE2. Bonds started to rally and interest rates started to fall in anticipation of more quantitative easing. The announcement came in November 2010 (Point 4). Interest rates immediately started to rise.

Point 5 marks the end of QE2. You can see rates were higher at the end of the program than at the beginning. Once again, any gains in bond prices occurred in anticipation of QE, not because of it.

Of course, ever since QE2 ended in July 2011, we’ve been looking forward to QE3. Bonds have rallied, and rates have fallen. Two months ago, the 10-year yield dropped to an historic low of 1.4% in anticipation of a QE3 announcement.

We got that announcement last week (Point 6). Rates have been rising ever since… And they’re going to keep rising. Here’s why…

QE3 is open-ended. There is no end date. We have the Fed’s assurance that it will drop buckets of money on the market for as long as necessary. There’s nothing left for bond investors to anticipate. We won’t see bond prices rally and interest rates fall again in anticipation of the Fed doing anything. It just promised to do everything.

From here on out, the only thing to anticipate is when the Fed will stop.

At some point, the Fed will stop dumping $40 billion per month into the bond market. It’ll stop artificially manipulating interest rates. It’ll turn on the lights and take the punchbowl away. No one wants to be invested in bonds when that happens.

Bond investors are going to sell, anticipating the end of the party. With every piece of economic news that comes out, bond investors will wonder, “Is this report going to be strong enough to cause the Fed to stop?” And they’ll sell ahead of time.

By announcing an unlimited amount of QE, the Fed shifted the focus of the bond market. Instead of wondering when we’ll get more, the question now is when it will end.

Basically, the Fed just destroyed the bond market.

The only hope bond buyers now have for lower interest rates is if the stock market corrects. Falling stock prices will spook investors and maybe push them into the perceived “safe haven” of the Treasury bonds market. As a bond investor, that will be your best chance to get out.

As a trader, it’ll be your best chance to short Treasury bonds.

Best regards and good trading,

Jeff Clark

Further Reading:

Jeff has been anticipating the announcement of QE3. In June, he explained how to take advantage of it in the stock market.And in July, he showed readers why thebond market was in a lose/lose situation with more money printing.

Most of you reading this expect inflation in the years ahead, right? Well, I don’t. In fact, I am firmly in the deflation camp.

Just think about it. What has happened after every major

We got deflation in prices… every time.

This time around, with the latest bubble peaking in 2007/08, the outcome will be exactly the same. There is deflation ahead. Expect it. Prepare for it.

But the bubble-bust cycle that history has allowed us to see is not the only reason I’m so certain we’re heading for deflation and a great crash ahead. I have other, irrefutable evidence…

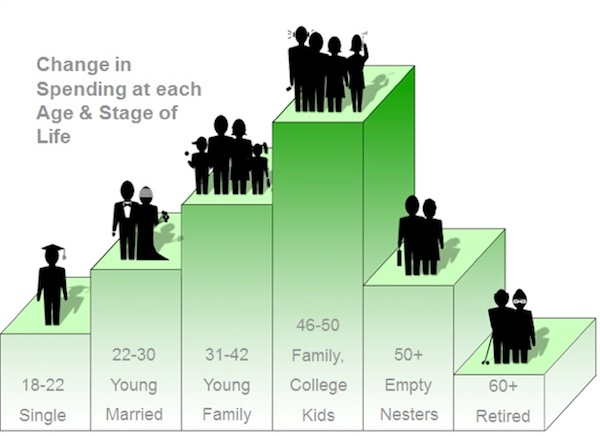

For one, there is the most powerful economic force on Earth: demographics. More specifically, the power of the number 46. You see, that’s the age at which the average household peaks in spending.

When the average kid is born, the average parent is 28. They buy their first home when they’re 31… after they had those kids. When the kids age into nasty teenagers, the parents buy a bigger house so they can have space. They do this between the ages of 37 and 42. Their mortgage debt peaks at age 41. And like I said, their spending peaks at around 46.

From cradle to grave, people do predictable things… and we can see these trends clearly in different sectors of our economy, from housing to investing, borrowing and spending, decades in advance.

This demographic cycle made the crash in the ’30s and the slowdown in the ’70s unavoidable. Now it is happening again… with the biggest generation in history – the Baby Boomers.

Consumer spending makes up more than two-thirds of our gross domestic product (GDP). So knowing when people are going to spend more or less is an incredibly powerful tool to have. It tells you, with uncanny accuracy, when economies will grow or slow.

Why Deflation Is the Endgame

Think of it this way: the government is hellbent on inflating. It’s doing so by creating debt through its quantitative easing programs (just for starters). But what’s the private sector doing? It’s deflating.

And the private sector is definitely the elephant in the room. How much private debt did we have at the top of the bubble? $42 trillion. How much public debt did we have back then? $14 trillion.

That looks like a no-brainer to me. Private outweighs public three to one. And the private sector is deleveraging as fast as it can, just like what happened in the 1870s and 1930s. History shows us that the private sector always ends up winning the inflation-deflation fight.

Now, I will concede that this is an unprecedented time. Today governments around the world have both the tools and the determination to fight deflation. And they are desperate to keep it at bay because they know how nasty it is (they, too, are students of history).

How bad is it? Think of deflation like what your body would do with bad sushi. It would flush it out as fast as possible. That’s what our system is trying to do with all the debt we accumulated during the boom years. It’s what the system did in the 1930s. Back then we went from almost 200% debt-to-GDP to just 50% in three years. It hurt like hell. The government doesn’t want this painful deleveraging.

The problem is, the longer the government tries to fight this bad sushi, the sicklier the system becomes. I know this because it’s what happened to Japan…

Japan’s bubble peaked in the ’80s. When the unavoidable deleveraging process began, the country did everything in its power to stop it. How is Japan doing today, 20 years after its crash? It is still at rock bottom. Its stock market is still down 75%.

Japan has gone through everything we’ll go through in the next few years. Does Japan have an inflation problem? That’s a rhetorical question. Did its central bank stimulate frantically? Also a rhetorical question.

Think of it another way: what is the biggest single cost of living today? Is it gold? Oil? Food? It’s none of these. It is housing. And what is housing doing? Dropping like a rock. It can’t muster a bounce, despite the lowest mortgage rates in history and the strongest stimulus programs anywhere… ever.

The Fed is fighting deflation purposely. It will fail.

Why the Fed Will Fail in All Its Efforts

There is simply no way the Fed can win the battle it’s currently waging against deflation, because there are 76 million Baby Boomers who increasingly want to save, not spend. Old people don’t buy houses!

At the top of the housing boom in recent years, we had the typical upper-middle-class family living in a 4,000-square-foot McMansion. About ten years from now, what will they do? They’ll downsize to a 2,000-square-foot townhouse. What do they need all those bedrooms for? The kids are gone. They don’t visit anymore. Ten years after that, where are they? They’re in 200-square-foot nursing home. Ten years later, where are they? They’re in a 20-square-foot grave plot.

That’s the future of real estate. That’s why real estate has not bounced in Japan after 21 years. That’s why it won’t bounce here in the US either. For every young couple that gets married, has babies, and buys a house, there’s an older couple moving into a nursing home or dying.

I watch this same demographic force move through and affect every other sector of the economy. The tool I use to do so is my Spending Wave. This is a 46-year leading indicator with a predictable peak in spending of the average household.

Here’s how it works: the red background in the chart above is the Dow, adjusted for inflation. The blue line is the spending wave, including immigration-adjusted births and lagged by 46 years to indicate peak spending. If you ask me, that correlation is striking.

The Baby Boom birth index above started to rise in 1937. It continued to rise until 1961 before it fell. Add 46 to 1937, and you get a boom that starts in 1983. Add 46 to 61, and you get a boom that ends in 2007.

Today demographics matters more than ever because of the 76 million Baby Boomers moving through the economy. That’s why I don’t watch governments until they start reacting in desperation. Then I adjust my forecasts accordingly.

Don’t Hold Your Breath for the Echo Boomer Generation

But all this talk about Baby Boomers inevitably births the question: “Surely the Echo Boom generation is coming up right behind their parents. They’ll fill the holes, right?”

Let me make this clear. If I hear one more nutcase on CNBC say, “The Echo Boom generation is bigger than the Baby Boom,” I might go ballistic. They are wrong. The Echo Boomer generation is NOT bigger than the Baby Boom generation. In fact, it’s the first generation in history that’s not larger than its predecessor is, even when accounting for immigrants.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. We will see another boom around 2020-23. But for now, all the Western countries will slow, thanks to the downward demographic trend sweeping the world. Some are slowing faster than others are. For example, Japan is slowing the fastest (it actually committed demographic kamikaze, but that’s a discussion for another day). Southern Europe is next along in its decline. Eastern Europe, Russia, and Asia are following quickly behind.

Which brings me back to my point: there is no threat of serious inflation ahead. Rather, deflation is the order of the day. The Fed thinks it can prevent a crash by getting people to spend. To that I say, “Good luck.” Old people don’t spend money. They bribe the grandkids, and they go on cruises where they just stuff themselves with food and booze.

Do you know how to tell if you’re buying a car from an older person? It’s going to be ten years old and have only 40,000 miles on it. They drive 4,000 miles a year. They just go down the street to get a Starbucks coffee and a newspaper. Then they go back home. How do you know you’re buying a car from a soccer mom? It’s driven 20,000 miles a year, carting the kids around all day… to school, soccer practice, whatever. This is the power of demographics.

So let me tell you what causes inflation. It’s young people. Young people cause inflation. They cost everything and produce nothing. That’s inflation in people terms.

Why did we have high inflation in the ’70s? Because Baby Boomers were in school, drinking, spending their parents’ money. While this was going on, we experienced the lowest-productivity decade in the last century.

Do you remember the 1970s? We had worsening recessions as the old Bob Hope generation began to save more while the Baby Boomers entered the economy en masse… at great expense. It costs a lot of money to incorporate young people, raise them, and put them into the workforce.

Then suddenly, in the early ’80s, like some political genius did something brilliant, the economy started growing like crazy, and inflation fell. You know what that was? That was the largest generation in history transitioning en masse from being expensive, rebellious, young people to highly productive yuppies with young new families. It was the move from cocaine to Rogaine.

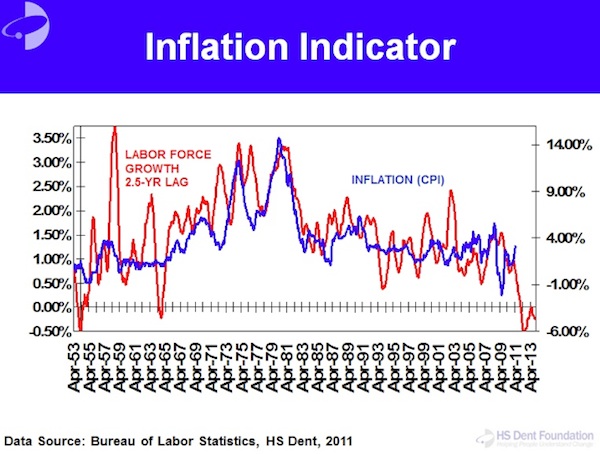

The correlation between labor force growth and inflation is crystal clear…

When lots of young people come into the labor force, it’s inflationary. When lots of old people move out of the labor force and into retirement, it’s deflationary. Right now, where is the highest inflation in the world? It’s in emerging countries. Do they have more old people or young people? They have more young people.

We saw it in the 1970s, we see it in emerging markets, and we’ll see it ahead as the Baby Boomers head off into the sunset. First, there was inflation. Ahead is deflation. No doubt about it.

Harry Dent, the editor of Boom & Bust, has put together a free report for John Mauldin’s readers, called: Survive and Prosper in This Winter Season: Take These Steps Now… Before Dow 3,300 Arrives. You can access this free report by clicking on this link:http://www.boomandbustinvestor.com/reports/current/BoomandBustInvestor_WinterSeason.pdf