Bonds & Interest Rates

Quite a surprise when Gold fell into a bear market in reaction to the Fed’s 2011 QE III – the nearly unlimited money-printing blitz. A historical review tells us when we can expect inflation and another important underlying force that you need to understand….

Inflation?

The most frequently asked question I seem to get, even these days, is: “Larry, don’t you see hyperinflation for the U.S. in the years ahead?”

So let me clarify my position, here and now. There was a time when I expected the U.S. economy would eventually experience hyperinflation.

But when the price of gold failed to react to the Fed’s QE III announcement of virtually unlimited money-printing in September 2011 and the yellow metal entered a bear market, I knew something had radically changed.

So I further researched the known periods of hyperinflation in the world. And I found something that completely changed my view: There has never been a major core economy that has died at the hands of hyperinflation.

There was the Weimar Republic, of course, but it was not a core economy for the world. There are the hyperinflations of Zimbabwe, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela now and countless other small economies that were never at the core of the global economy.

And upon further study, I found that even the Roman Empire, certainly a core economy during its reign, didn’t even die of hyperinflation.

And upon further study, I found that even the Roman Empire, certainly a core economy during its reign, didn’t even die of hyperinflation.

It died largely because of abuse of power by politicians, which drove citizens away from the Empire; because of rapidly rising taxation, which had the same effect; and because of a corrupt treasury and justice system that tracked down and confiscated citizens’ wealth, largely to fund increased military campaigns, which were hoped to revive the Roman economy. Sound familiar?

Was there high inflation in Rome before it fell? Yes, but nothing of the sort of hyperinflation like we subsequently saw in Weimar Germany or any of the countries I mention above.

So, then, what does the U.S. economy face? Further disinflation, eventual reflation or something else?

My view, and I am not hedging my answer or talking out of both sides of my mouth: We face a combination of further disinflation in the short term, followed by a rather large jump in inflation a few years from now.

How high will inflation eventually go? Hard to say, but I wouldn’t be surprised if, say, three years from now, we see 20% or even 25% inflation for a very brief period of time.

But I highly doubt we will ever see inflation in the thousands or even millions of percent. It’s just not possible in a core economy. For many different reasons.

Whether we have deflation or inflation is also the wrong way to think about the U.S. economy these days. The reason? Ever since we abandoned the gold standard, inflation and deflation have become two sides of the same coin.

In other words, they are both present in the economy at the same time. You can have certain goods and services and even asset classes deflating, while others are inflating. It’s as simple as that.

For instance, the price of LED TVs has crashed in the past year or so, as have the prices of laptop computers and many other goods.

So it’s not a matter of one or the other, it’s a matter of what sector is inflating and why, versus which sectors are deflating and why.

Nevertheless, there’s another important underlying force that you need to understand, another one that resulted from the abolishment of the gold standard.

A certain level of general, system-wide inflation is always baked into the cake. It’s due, again, to the fact that we no longer have a gold standard, but it’s also due to many other forces, such as population growth, limited availability of natural resources, the constant desire for people to improve their lives and more.

This is important to understand, because it’s the chief reason prices will be higher a year from now, five years from now and even 10 years from now … no matter what the U.S. or global economy does.

And it’s also why investing in gold — just after it experiences a short-term disinflationary trend — is an ideal strategy to jump on.

Speaking of gold. It looks good now. But you don’t want to buy it at these levels. Gold’s new bull market is just getting started. Let it prove itself by first pulling back — which it will do, to below $1,200 …

Then back up the truck. Ditto for other precious metals and especially mining shares.

Best wishes,

Larry

related: Billionaire George Soros Cuts U.S. Stocks Position – Buys Barrick Gold

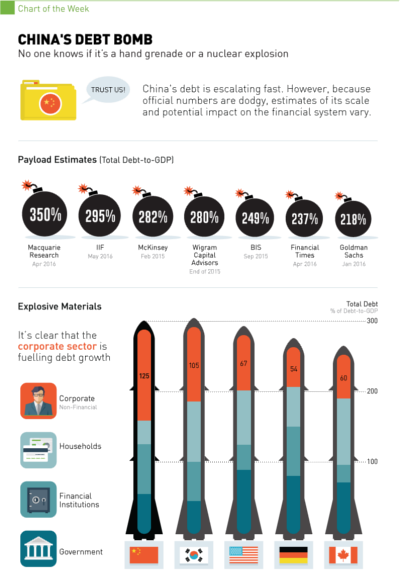

If the Chinese debt bomb is detonated, the impact on markets is anybody’s guess.

If the Chinese debt bomb is detonated, the impact on markets is anybody’s guess.

Kyle Bass says the losses will be 5x that of the subprime crisis, while Moody’s claims it won’t detonate at all.

In today’s chart, we look at the potential trigger for ignition.

….click HERE or Chart for larger view and analysis

related:

China Stops Trying To Fool The World

Something interesting has happened. China earlier this year responded to falling stock prices by borrowing a trillion dollars and spending it on commodities, boosting the prices of iron ore, oil, copper, etc., and giving the global economy a patina of recovery.

Something interesting has happened. China earlier this year responded to falling stock prices by borrowing a trillion dollars and spending it on commodities, boosting the prices of iron ore, oil, copper, etc., and giving the global economy a patina of recovery.

Nothing unusual so far. China did the same thing in response to 2008’s Great Recession, and the world breathed an appreciative sigh of relief, ignoring the massive new leverage that the policy involved.

Which is why the past month has been so interesting. Instead of just accepting China’s largess and blithely assuming that all was once again well, the global financial media have chosen (for perhaps the first time ever outside of a full-on crisis) to focus on the negative aspects of rising leverage. They’re now anticipating trouble for China, with titles like:

China’s debt problem is bigger than you think

Chinese banks grappling with ‘crisis level’ bad debts

CLSA Sees China Bad-Loan Epidemic With $1 Trillion of Losses

The $571 Billion Debt Wall That Points to More Defaults in China

To call thus unusual is a huge understatement. And it seems to have made a difference. Yesterday China announced a fairly radical course change:

Even China’s Party Mouthpiece Is Warning About Debt

(Bloomberg) – China’s leading Communist Party mouthpiece acknowledged the risks of a build-up of debt that is worrying the world and said the nation needed to face up to its nonperforming loans.

High leverage is the “original sin” that leads to risks in the foreign-exchange market, stocks, bonds, real estate and bank credit, the People’s Daily said in a full-page interview with an unnamed “authoritative person” starting on page one and filling the second page on Monday.

China should put deleveraging ahead of short-term growth and drop the “fantasy” of stimulating the economy through monetary easing, the person was cited as saying. The nation needs to be proactive in dealing with rising bad loans, rather than delaying or hiding them, the report said.

“Overall, the report suggests to us that future policy easing may be more cautious and that the government may try to hasten the pace of reform,” said Zhao Yang, chief China economist at Nomura Holdings Inc. in Hong Kong. Similar commentaries have had a “large impact” in the past, the analyst said in a note.

The pace of China’s accumulation of debt and dwindling economic returns on each unit of credit have fueled concern that the nation is set for either a financial crisis or a Japanese-style growth slump. Strong growth in mortgage lending means that banks could be exposed to significant losses should property prices drop sharply, Fitch Ratings said in a statement dated Sunday.

“A tree cannot grow up to the sky — high leverage will definitely lead to high risks,” the person was cited as saying. “Any mishandling will lead to systemic financial risks, negative economic growth, or even have households’ savings evaporate. That’s deadly.”

China’s accumulation of debt has been the fastest of Group of 20 members over the past decade, according to Tom Orlik, an economist for Bloomberg Intelligence. Debt has climbed to 247 percent of gross domestic product, Bloomberg Intelligence estimates.

Volatility in stocks and the foreign-exchange market early this year had partly reflected the vulnerability of the financial system, the article said.

The newspaper piece touched on the topic raised by Premier Li Keqiang of banks swapping debt for equity to cut excess borrowing by Chinese firms.

While bankruptcies should generally be avoided, “zombie” companies beyond salvage should be allowed to fail because debt-to-equity swaps would be costly and self-deceiving, the commentary said.

Supply-side reform will remain the focus of economic policies for the near future, the article said. While the economy can grow sufficiently without stimulus, its performance will be “L-shaped,” not a “U” or a “V,” for quite some time, rather than just a year or two, the commentary said.

Traders responded to this sudden honesty by selling pretty much everything:

Metals, Mining Stocks Sink as Chinese Data Signal Weak Demand

(Bloomberg) – Industrial metals fell while mining stocks dropped the most in six weeks as a slump in Chinese copper purchases and an increase in steel exports signaled weak demand in the top user.

The decline in commodities deepened on Monday after China copper imports fell from a record while exports of steel in the first four months rose 7.6 percent from a year earlier. Iron-ore futures in Asia plummeted after port stockpiles in China expanded to the highest in more than a year.

“A morning of widespread price retreats along with iron ore as Chinese demand appears to stumble again,” Michael Turek, the head of base metals at BGC Partners Inc. in New York, said in an e-mail. “April’s lower copper imports raises questions about the March spike.”

Copper futures for July delivery dropped 2 percent to $2.111 a pound at 10:42 a.m. on the Comex in New York, after earlier touching $2.1025 a pound, the lowest in almost a month.

The Bloomberg Americas Mining Index slumped as much as 4.8 percent in New York, the steepest intraday decline since March 23.

Some Thoughts

China is the latest in a growing line of “command and control” economies that have risen to prominence, captured the imagination of people who find free markets too messy for comfort, and then blown up when it turns out that dictators have no idea how to allocate capital.

First it was the Soviet Union, which looked during its initial decades like a viable alternative to market-based systems. From journalist Lincoln Steffens’ famous 1919 observation “I have seen the future and it works” to the 1957 launch of Sputnik, an amazingly-large number of people assumed that it was possible for a handful of men sitting around a conference table to efficiently organize a modern economy. It eventually became clear that they were wrong.

Then came Japan, which emerged from the rubble of WWII to become a global economic power, largely be grafting its semi-feudal samurai tradition onto factory life — under the direction of its Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI). That is, guys sitting around a table deciding what gets built where. This resulted in an epic debt and mal-investment binge from which Japan may never recover.

And now comes China’s hybrid Japanese/Soviet model, with various Communist Party organs and shadow banking system entities directing investment from the top down, borrowing immense amounts of money and plucking growth figures out of thin air, which Western media accept at face value. It too seems to be failing, which should come as no surprise but — given the numbers involved — should scare the hell out of anyone with a sense of history.

related: Central Banks Roil Markets M/T Editor

Summary

Summary

- Bond managers are supposed to hate inflation, but Janus Capital’s Bill Gross – a long time Fed critic – reverses course and asks for massive QE to support jobless Americans.

- Chris DeMuth Jr. finds a fund that may be a good investment after it has swindled enough investors to make its discount attractive.

- Ian Bezek offers advice on how to invest in light of the Trump victory he sees as likely in November’s general election.

related:

Negative Interest Rates Claim More Victims. Today It’s Deutsche Bank, Tomorrow German Insurers?

These are shockingly bad times for big banks, especially when you consider that the overall economy is supposed to be fairly healthy. The latest example is Germany’s Deutsche Bank:

Deutsche Bank Q1 ‘most challenging in several decades’: CFO

(CNBC) – Deutsche Bank posted a 58 percent drop in net profit in the first quarter, to 236 million euros ($267 million) compared to the same period last year.

The group posted a revenue decline of 22 percent year-on-year to 8.1 billion euros which it said “reflected a challenging environment and the impact of strategic decisions to downsize and exit certain businesses.”

In its core business, revenue dropped 15 percent in its corporate and investment banking division and 23 percent in its global markets unit. It said 2016 would be the “peak year for its restructuring efforts.”

Shares of the bank rose 4 percent in early trade on Thursday and the bank’s Chief Financial Officer Marcus Schenck told CNBC that there were highlights among the earnings.

“On the positive side, we made very good progress on implementing further steps on our journey, as in the focusing of the bank, we’re exiting certain countries, we’re exiting certain market positions and all of that is evidenced in a risk-weighted asset position that we have as per the end of the quarter.”

Nonetheless, Schenck conceded that the first quarter had been one of the most difficult in the bank’s recent history.

“I can’t debate away that this has been one of the most challenging quarters over the last several decades,” he said, “(But) we’ve seen the markets calm down a lot in March and April and the performance in those two last months is definitely better.”

Schenck said he had no “crystal ball” to see if the rest of the year would pan out. “There is still a lot of uncertainty out there and there is the ‘Brexit’ question (the U.K. referendum on EU membership in June) and with China, it doesn’t look like there’s going to be a hard landing as some people had feared but still, things can go wrong.”

In the fourth quarter, the bank posted a net loss of 2.1 billion euros and full-year net loss (and a record loss) of 6.8 billion euros in 2015.When that data was released in late January, the chief financial officer Marcus Schenck said he expected 2018 to the first “clean” year for the bank as the lender continued to struggle with writedowns, litigation charges and restructuring costs.

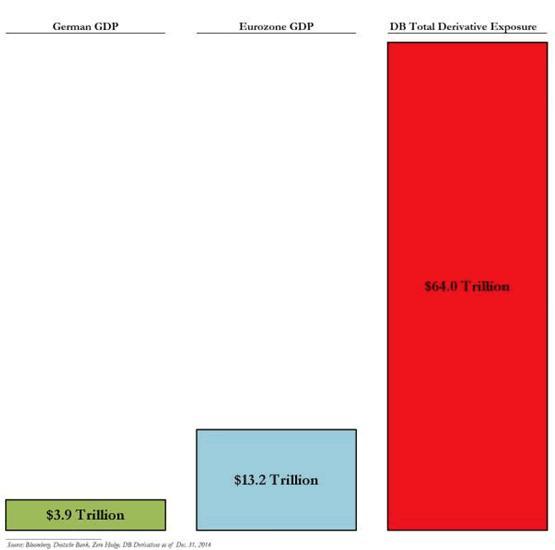

For an entity as big and supposedly diversified as Deutsche Bank to post not just a 58% drop in profits but a 22% decline in revenues is “challenging” indeed. And it draws the eye to the risks these guys have taken on via an over-the-counter derivatives book that is, well, surreal. The following chart originally appeared in a Zero Hedge article.

So the odds that whatever DB management is doing today will fix this mess are pretty slim. Especially if the environment of negative interest rates, zero inflation and slow growth remains in place, as it almost certainly will.

But horrendously badly managed banks are just the tip of the iceberg. Negative interest rates are a mortal threat to all kinds of other financial business models, including insurance companies:

Germany: Where Negative Rates Are Lethal

(Wall Street Journal) – German life insurers are caught in a pinch that could eventually threaten their survival. Regulators are forcing them to boost capital levels at the same time that low rates make it hard to make money with their investments.

The question is how long before the ride gets bumpy enough to shake out the weakest firms.

German regulators are so concerned about the impact of negative interest rates on the country’s life insurers that they have said they can only be sure the sector is safe through 2018. Even today, half the industry would be short of capital without the help of special measures.

The trouble lies in the promises insurers made to policy holders years ago, when nobody would have guessed central banks around the world would send interest rates barreling toward zero, only to remain there for years on end and even break into negative territory.

The German life industry is particularly badly affected by very low or negative interest rates because companies have historically offered what now look like high levels of guaranteed returns over very long periods.

Some insurers need to earn a continuing investment yield of more than 5% to meet guarantees to their policy holders, a report from Germany’s central bank found in 2014. In a world where 10-year German government bonds yield less than one-quarter of 1%, that looks very hard to achieve.

Falling interest rates also increase the size of the liabilities on insurers’ balance sheets, which can reduce their capital if assets don’t increase in valuation enough to match.

Large European insurers such as Allianz SE,AXA SA, Assicurazioni Generali SpA andMunich Re all have big German life businesses, but regulatory concerns are more immediately focused on smaller insurers mainly unknown outside of the country. German life insurers earned gross written premiums of €89.9 billion ($101.4 billion) in 2014, according to the most recent statistics from German financial regulator BaFin.

One thing insurers can’t rely on is a respite on interest rates soon. The European Central Bank is struggling to boost inflation to its desired target, and one of its primary levers is to send interest rates lower. That leaves an open question as to where insurers can find investments with the right combination of yield and risk that will allow them to make good on their promises.

Think of what’s happening in global finance as an environmental change like a drought or temperature shift — that happens too quickly for the ecosystem to adapt. Not every organism dies immediately, but relationships and inter-dependencies are disrupted, killing some and impairing others. Then comes a mass die-off in which a wide range of species disappear.

That, in a nutshell, is what a negative rate world means for banks, insurance companies, money market funds, pension funds, retirees, small savers and pretty much everyone else who depends on substantial risk-free income. The elephants like Deutsche Bank will make a lot of noise when they fall, but for each giant there are hundreds of smaller entities adapted for a very different world and unable to live in this one.

related:

Martin Armstrong: “Draghi is absolutely clueless”