Bonds & Interest Rates

Bill Gross of Janus Capital Management joined Bloomberg Radio and Television to react to today’s jobs report.

Bill Gross of Janus Capital Management joined Bloomberg Radio and Television to react to today’s jobs report.

Gross said the Federal Reserve is “certainly set to go…Fed is ready to go I think because of concerns on the real economy.”

When asked if he lost money yesterday, Gross said: ” Oh no, made money yesterday. I had lots of calls, sold lots of calls on five and 10-year German bunds, went the other way this time and so made a lot of money, making a lot of money today on those particular trades.”

MICHAEL MCKEE: I guess this one is in train now.

BILL GROSS: Well, yes, they are certainly set to go. And it’s something that I have been encouraging for a while, not because of the

tightness of the labor market or the fact that wages are increasing. As a matter of fact, wages were up 0.2 percent and the YOY is 2.3 percent relative to 2.5. So there is no pressure from the standpoint of wages, but the Fed is ready to go I think because of concerns on the real economy.

And it’s going to be an interesting experiment over the next three months or so, I’d say, they shift to a new policy in terms of determining the Fed funds rate, the — using the excess reserves in terms of an interest rate as a top, and using reverse repos as a bottom. They’re going to have to work with that.

TOM KEENE: And I think they’re going to need at least three months to make sure it’s smooth.

KEENE: Bill Gross, you wrote about Wiley Coyote yesterday. I don’t think that translates in Paris, France too well. So what I would suggest, Bill, is please address for the international audience how Janet Yellen can avoid international mediocrities, including the challenges Mario Draghi has.

GROSS: Well the Fed has sort of backed off of their QE almost 12 months ago. Draghi continues. And Draghi’s policy statement yesterday was quite interesting because he gave the market most of what they wanted. He’s still in a whatever it takes mode.

He did give them quantitative easing for six more months. He included additional assets. It seemed like a very stimulative type of forward statement, but the market I think had a sense that since the amount wasn’t increased that perhaps the ECB is the last bastion of quantitative easing and monetary, easing policy basically is at its limits.

KEENE: Right. Mike, I want to cut in here. This is an incredibly important question. Bill Gross, how many billions of dollars did you lose yesterday?

GROSS: Oh no, made money yesterday. I had lots of calls, sold lots of calls on five and 10-year German bunds, went the other way this time and so made a lot of money, making a lot of money today on those particular trades. So I think the U.S. is in a better position in terms of their yields relative to Germany and the EU, although to be fair, if $60 billion a month has been extended by six months and we’ve got with 18 months to go that’s a trillion euros to go, and that puts their balance sheet close to EUR4 trillion euros relative to the Fed’s balance sheet of EUR4 trillion with a much larger economy. So there is a lot of firepower left, and it pays to be careful when a central bank employs what I call a Martingale strategy, which is basically double up to catch up.

MCKEE: Well we thought until the Mario Draghi press conference yesterday, Bill, that we had a narrative going. They were stimulating. We were going to start raising rates and you would see the divergence trades in place. It could be predicted, but now it seems like what has brought back to the market is a lot of volatility, and we can’t necessarily say we’re going to see a big bond selloff here in the United States, and the opposite overseas, and the dollar gets stronger and the euro get weaker. We’re not sure what’s going to happen.

GROSS: And the United States has for the last 12 to 24 months have been talking about the new neutral interest rate. Right now the forward market in terms of Fed funds is basically forecasting the 80 to 85 basis points higher from a year from now, and then another 60 or so two years from now and then another 40 or so three years from now. So the pace, the expected pace is like 75, 50, 50. And that eventually takes us up to close to two percent, which is what I think is the neutral level given normal economic conditions.

KEENE: Bill, one more question and then we want to get to Alan Krueger of Princeton University helping out this half hour. Bill Gross, I’m sitting here in the city hall of Paris. And the basic idea is this is the land of perpetuity bonds. Is the thing that America is missing in our new fixed income world that we need longer duration bonds? Do they make sense for investors?

GROSS: Well not really at these levels do they? I mean and let’s talk about pension funds, and I know you mean individual investors, but basically the same thing. Do they want to lock in future liabilities basically at a three percent level for a 30-year treasury or, amazingly, at a 2.69 percent level for a 30-year swap, to get a little esoteric?

KEENE: Yes.

GROSS: But anyway, does that pay the bills going forward? I don’t think so. You know that for sure by looking at pension estimates they expect seven to 7.5 percent in terms of a 50/50 stock and bond mix. Do individual investors get that from a three percent long bond? I don’t think so. I think it pays for the treasuries of these countries to issue long debt, as opposed to individuals and corporations to buy them.

MCKEE: Bill, we’ve got Alan Krueger of Princeton University here. Alan, we’ve got time for a quick question for Bill if you’ve got one.

ALAN KRUEGER: Well I guess I was a little bit confused on the long bonds. If you think there’s not going to be much demand for them, wouldn’t the interest rates be lot higher than three percent?

GROSS: Well there’s not going to be a lot of issuance, first of all, as you know, next year from the treasury, going to be very mild period of time in terms of issuance. And there is still accumulation from Japan and from China, plus or minus. We’re not quite sure what China does, but there is demand there. And there is demand, Alan, from corporations, surprisingly. I don’t think there should be, but there is demand because they issue debt and then they basically hedge it out and turn it into short-term debt by basically receiving or buying long-term swaps.

That’s a strange situation these days in terms of financial markets and in terms of the varying interest, but it seems to me that if Fed funds peak at two percent during this particular cycle that there’s not much downside in price, and not much upside in yield for U.S. treasuries to buy. I would simply favor them versus German bunds or anything in Europe, still in a negative camp up to five years of course.

Today’s the big day…

Today’s the big day…

Mario “whatever it takes” Draghi is expected to goose up stock markets with more stimulus measures.

On the table is more QE… and further cuts to the key lending rate.

The Chinese feds are also supposed to come forward with another gift to asset holders.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the expectation is for something targeting property purchases and another interest rate cut (which would make it cut No. 7 since last November).

And yesterday, Fed chair Janet Yellen told the Economic Club of Washington:

|

In Europe, Asia, and America, central bankers, we are told, have the situation in hand.

Fools or Knaves?

But these policies – in fact ALL central bank policies for the last 30 years – are either a mistake or flimflam.

…they are perpetrated by either fools or knaves… depending on how you look at it.

…and they are either an intentional transfer of wealth from the people who earned it to the world’s elite insiders. Or the transfer of wealth is an unintended consequence of botched policy.

We lean toward the larceny explanation.

QE may have been a mistake when it was first tried by Japan 20 years ago. But after so many years of trial and error, we now know how it works: It takes wealth from some people (mostly middle-class savers) and gives it to others (mostly wealthy speculators).

This is a problem. Because we know from both theory and experience that trying to rob the rich to make the poor better off doesn’t work. The rich duck and dodge. And the poor lose the incentive to make it on their own.

Now, we’re discovering that the opposite approach doesn’t work either. You can’t rob the poor, give to the rich, and expect the economy to improve.

Already, the European Central Bank’s key lending rate is MINUS 0.2%. We have been amazed and befuddled by these negative rates for a long time. They suggest an impossibility: That the value of money is less than nothing. And if that is so, the value of everything money buys – including labor – must also be less than zero…

…which is such a strange and preposterous thought that it can’t be correct.

But after a few nights of light meditation and heavy drinking – aided by insights from Charles Gave, the chairman of Gavekal Research – we think we have a better understanding of it.

An Affront to Nature

First, says Charles, negative rates are an affront to nature… and an insult to the gods.

Money today is inherently worth more than the same amount of money a year from now. Because something could happen in the intervening period. Someone else could buy the house you wanted. The borrower might die and not pay you back. Or you might die, without ever seeing your money again.

That’s why lenders need to be paid for the risk that something will go wrong…

Meanwhile, the Old Testament tells us that God chased Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, with this curse: From now on, “you will earn your bread from the sweat of your brow.”

But the goal of central bank demand management is to upset God’s applecart. The feds want people to consume their bread before they even put on their work gloves.

In the long run, this clearly won’t work. Spending credit is essentially spending someone else’s money. And sooner or later you will run out of other people’s money.

Lord Keynes – from whom the feds draw inspiration – said not to worry. In the long run, he said, we’re all dead anyway.

Keynes is dead. And we are in the long run now.

Regards,

Bill

Further Reading: Bill says that spending credit is spending someone else’s money… and sooner or later you will run out. In his latest investor presentation, Bill reveals the frightening truth of what will happen when the feds finally do run out of other people’s money to spend. It’s going to happen sooner than you think… and the consequences will be worse than anything the world has ever seen. Watch Bill’s warning now.

Yellen, in back-to-back appearances, could close out era of zero rates.

Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen could cement the case for a U.S. interest rate hike ahead of the Fed’s Dec. 15-16 policy meeting, with public appearances over the next two days at a high-profile economics group and before a joint committee of Congress.

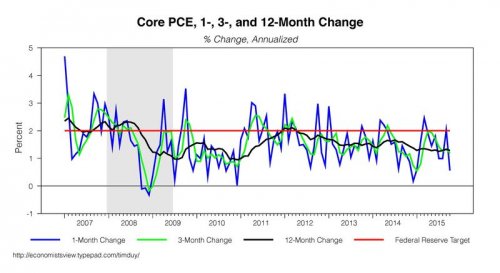

The latest read on the Fed’s preferred inflation metric was not particularly kind to policymakers:

this is only one of a number of indicators that should give a reality check to FOMC participants as December’s meeting approaches. A stronger dollar, weaker commodity prices, and falling inflation expectations suggest that the “transitory” negative weights on inflation might persist longer than the Fed anticipates.

I remember how in 2003 the late legendary Barton Biggs, a strategist for Morgan Stanley, proclaimed in one of his Investment Perspectives that 10-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs) were “the short of the century.” Japan had just gone through 10 years of deflation and the 10-year JGB yields had gone from nearly 8% at the time of the all-time high in the Nikkei 225 benchmark index (at near 40,000 in December 1989) to a hair shy of 40 basis points (0.4%) in 2003.