Bonds & Interest Rates

Late last week, a consortium of financial regulators in the United States, including the Federal Reserve and the FDIC, issued an astonishing condemnation of the US banking system, highlighting “continuing gaps between industry practices and the expectations for safe and sound banking.” They identified a huge jump in risky loans due to overexposure to weakening oil and gas industries. Make no mistake; this is not chump change. The total exceeds $3.9 trillion worth of risky loans that US banks made with your money. Given that even the Fed is concerned about this, alarm bells should be ringing….continue reading HERE

Late last week, a consortium of financial regulators in the United States, including the Federal Reserve and the FDIC, issued an astonishing condemnation of the US banking system, highlighting “continuing gaps between industry practices and the expectations for safe and sound banking.” They identified a huge jump in risky loans due to overexposure to weakening oil and gas industries. Make no mistake; this is not chump change. The total exceeds $3.9 trillion worth of risky loans that US banks made with your money. Given that even the Fed is concerned about this, alarm bells should be ringing….continue reading HERE

Due to the nature of modern money, it would technically be possible to adjust the way the monetary system works such that governments directly print all the money they need. If this change were made then there would be no requirement for the government to ever again borrow money or collect taxes. This would have an obvious benefit, because it would result in the dismantling of the massive government apparatus that has evolved to not only collect taxes but to monitor almost all financial transactions in an effort to ensure that tax collection is maximised. In other words, it would potentially result in greater freedom without the need to cut back on the ‘nanny-state services’ that so many people have come to rely on. So, why isn’t such a change under serious consideration?

Due to the nature of modern money, it would technically be possible to adjust the way the monetary system works such that governments directly print all the money they need. If this change were made then there would be no requirement for the government to ever again borrow money or collect taxes. This would have an obvious benefit, because it would result in the dismantling of the massive government apparatus that has evolved to not only collect taxes but to monitor almost all financial transactions in an effort to ensure that tax collection is maximised. In other words, it would potentially result in greater freedom without the need to cut back on the ‘nanny-state services’ that so many people have come to rely on. So, why isn’t such a change under serious consideration?

The answer is that it would expose the true nature of modern money for all to see, leading to a collapse in demand for the official money. Taxation, you see, isn’t just a method of forcibly diverting wealth to the government; it is also an indispensable way in which demand for the official money is maintained and modulated.

Think of it this way: If the government were to announce that in the future there would be no taxation and that it would simply print all the money it needed, there might initially be a great celebration; however, it probably wouldn’t take long for the average person to wonder why he/she should work hard to earn something that the government can create in unlimited amounts at no cost. People would become increasingly eager to exchange money for tangible items, causing prices to rise. The faster that prices rose due to the general decline in the desire to hold money, the faster the government would have to print new money to pay its expenses. With no taxation and no government borrowing, there would be no way for the government to stop an inflationary spiral once it was set in motion.

One of the best historical examples of how taxation creates demand for money is the use of “tally sticks” in England from the 1100s through to the 1600s. In this case, essentially worthless pieces of wood were converted into valuable money by the fact that these pieces of wood could be used to pay taxes. Moreover, once taxation had created demand for the sticks, the government was able to fund itself by issuing additional sticks. A summary of the tally stick story can be read HERE.

Money can currently be created out of nothing by commercial banks and central banks, but hardly anyone understands the process. Also, many economists and so-called experts on monetary matters who understand how commercial banks create money are either clueless about the mechanics of central-bank quantitative easing (they wrongly believe that QE adds to bank reserves but doesn’t add to the economy-wide supply of money) or labouring under the false belief that money and debt are the same. The ones who wrongly conflate money and debt tend to wrongly perceive QE as a non-inflationary swap of one “cash-like” asset for another.

The point is that under the current system there is great confusion, even in the minds of people who should know better, regarding how the monetary system works. The combination of taxation and the general lack of knowledge about how money comes into existence helps support the demand for money.

Simplify the process by having the government directly print all the money it needs and the demand for money would collapse. That, in essence, is why taxation must continue.

###

Steve Saville![]() email: <ahref=”mailto:sas888_hk@yahoo.com”>sas888_hk@yahoo.com

email: <ahref=”mailto:sas888_hk@yahoo.com”>sas888_hk@yahoo.com

Hong Kong

Regular financial market forecasts and analyses are provided at our web site:

http://www.speculative-investor.com/new/index.html.

We aren’t offering a free trial subscription at this time, but free samples of our work (excerpts from our regular commentaries) can be viewed at: http://tsi-blog.com

Copyright ©2002-2015 speculative-investor.com All Rights Reserved.

Most economists and investors readily acknowledge that the current period of central bank activism, characterized by extended bouts of quantitative easing and zero percent interest rates, is a newly-blazed trail in economic history. And while these policies strike some as counterintuitive, open-ended, and unimaginably expensive, most express comfort that our extremely educated, data-dependent, central bankers have a pretty good idea as to where the trail is going and how to keep the wagons together during the journey.

Most economists and investors readily acknowledge that the current period of central bank activism, characterized by extended bouts of quantitative easing and zero percent interest rates, is a newly-blazed trail in economic history. And while these policies strike some as counterintuitive, open-ended, and unimaginably expensive, most express comfort that our extremely educated, data-dependent, central bankers have a pretty good idea as to where the trail is going and how to keep the wagons together during the journey.

But as it turns out, there really isn’t much need for guesswork. As the United States enters its eighth year of zero percent interest rates, we should all be looking at a conveniently available tour guide along the path of perpetual easing. Japan has been doing what we are doing now for at least 15 years longer. Unfortunately, no one seems to care, or be surprised, that they are just as incapable as we have been in finding a workable exit. When Virgil guided Dante through Hell, he at least knew how to get out. Japan doesn’t have a clue.

Despite its much longer experience with monetary stimulus, Japan’s economy remains listless and has continuously flirted with recession. In spite of this failure, Japanese leaders, especially Prime Minister Shinzo Abe (and his ally at the Bank of Japan (BoJ), Haruhiko Kuroda), have recently doubled down on all prior bets. This has meant that the Japanese stimulus is now taking on some ominous dimensions that have yet to be seen here in the U.S. In particular, the Bank of Japan is considering using its Quantitative Easing budget to buy large quantities of shares of publicly traded Japanese corporations.

So for those who remain in doubt, Japan is telling us where this giant monetary experiment leads to: Debt, stagnation and nationalization of industry. This is not a destination that any of us, with the possible exception of Bernie Sanders, should be happy about.

The gospel that unites central bankers around the world is that the cure for economic contraction is the creation of demand. Traditionally, they believed that this could be accomplished by simply lowering interest rates, which would then spur borrowing, spending and investment. But when that proved insufficient to pull Japan out of its recession in the early 1990s, the concept of Quantitative Easing (QE) was born. By actively entering the bond market through purchases of longer-dated securities, QE was able to lower interest rates across the entire duration spectrum, an outcome that conventional monetary policy could not do.

But since that time, the QE in Japan has been virtually permanent. Unfortunately, Japan’s economy has been unable to recover anything resembling its former economic health. The experiment has been going on so long that the BoJ already owns more than 30% of outstanding government debt securities. It has also increased its monthly QE expenditures to the point where it now exceeds the Japanese government’s new issuance of debt. (Like most artificial stimulants, QE programs need to get continually larger in order to produce any desirable effects). This has left the BoJ in dire need of something else to buy. Inevitably, it cast its eyes on the Japanese stock market.

In 2010 the BoJ began buying positions in Japanese equity Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs). These securities, which track the underlying performance of the broader Japanese stock market, are one step removed from ownership of companies themselves. After five years of the policy, the BoJ now owns more than half the entire nation’s ETF market. But that hasn’t stopped it from expanding the program. In 2014, it tripled its ETF purchases to $3 trillion yen per year ($25 billion), and the program may be tripled again in the near term. In just another example of how QE is a boon to the financial services industry, Japanese investment firms are currently issuing new ETFs just to give the BoJ something to buy.

However, these purchases have not proven to be particularly effective in doing much of anything, except possibly pushing up ETF share prices. But even that has been a mixed blessing. ETFs are supposed to be the cart that is pulled along by stocks (which function as horses). But trying to move the market by buying ETFs creates a whole other level of potential price distortions. It also tends to limit the impact to those holders of financial assets, rather than the broader economy. For this reason the BoJ is now contemplating the more direct action of buying shares in individual Japanese companies.

Such purchases would allow the Japanese government to accumulate sizable voting interests in some of Japan’s biggest companies. Equity ownership would then allow, according to an economist quoted in Bloomberg, the Abe administration to demand that Japanese corporations adhere to the government’s priorities for wage increases and heightened corporate spending. The same economist suggested, this “micro” stimulus provided by government controlled corporations may be more effective in spurring the economy than “macro” purchases of government bonds.

These possibilities should horrify anyone who still retains any faith in free markets. The more than four trillion dollars of government bonds purchased through the Federal Reserve’s QE program since 2008 now sit on account at the Fed. Although these purchases may have distorted the bond market, created false signals to the economy, and may loom as a danger for the future (when the bonds need to be sold), they are primarily a means of debt monetization, whereby the government sells debt to itself. But purchases of equities would involve a stealth nationalization of industry, and would represent a hard turn towards communism.

Many American observers will take comfort in their belief that the United States has already concluded its QE experiment and that we are heading in the opposite direction, toward an era of monetary tightening. This greatly misjudges the current situation.

The U.S. economy is slowing remarkably, and despite the continuous assertions by the Fed that rate hikes are likely in the very near future, I believe we are stuck just as firmly in the stimulus trap as Japan. The main difference between the U.S. and Japan is that Japan began this “experiment” from a much stronger economic position. Japan was a creditor nation, with ample domestic savings and large trade surpluses. In contrast, the U.S. started as the world’s largest debtor nation, with minimal savings, and enormous trade deficits. So if Japan, with its superior economic position, could not extricate itself from this trap, what hope does the United States have?

If the Fed is unable to raise rates from zero, it will also be have no ability to cut them to fight the next recession. So the next time an economic downturn occurs (one may already be underway), the Fed will have to immediately launch the next round of QE. When QE4 proves just as ineffective as the last three rounds to create real economic growth, the Fed may have to consider the radical ideas now being contemplated by the Bank of Japan.

So this is the endgame of QE: Exploding debt, financial distortion, prolonged stagnation, recurring recession, and the eventual government takeover of industry and the economy. This appears to be the preferred alternative of politicians and bankers who simply refuse to let the free markets function the way they are supposed to.

If interest rates were never manipulated by central banks and QE had never been invented, the markets could have purged themselves years ago of the speculative bubbles and mal-investments. Sure we could have had a deeper recession, but it also could have been much shorter, and it could have been followed by a far more robust and sustainable recovery.

Instead Washington has joined Tokyo on the road to Leningrad.

Best Selling author Peter Schiff is the CEO and Chief Global Strategist of Euro Pacific Capital. His podcasts are available on The Peter Schiff Channel on Youtube

Catch Peter’s latest thoughts on the U.S. and International markets in the Euro Pacific Capital Summer 2015 Global Investor Newsletter!

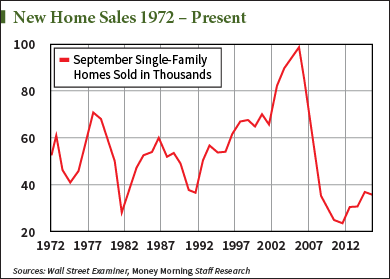

“Don’t believe any headlines that claim there’s a housing “recovery” in the United States. The truth is, there is no single family housing industry to speak of today”

“Don’t believe any headlines that claim there’s a housing “recovery” in the United States. The truth is, there is no single family housing industry to speak of today”

“What for generations was a main driver of U.S. economic growth has been brought down by the past seven years of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s zero-interest-rate policy (ZIRP)”

“Since ZIRP has failed to contribute to higher-paying jobs, fewer buyers can afford the price inflation that has been driving up prices”

“All is rosy again, except for the fact that global central bankers behave as if they’re utterly terrified of something”

“All is rosy again, except for the fact that global central bankers behave as if they’re utterly terrified of something”

‘More than two months have passed since the August “flash crash.” Fragilities illuminated during that bout of market turmoil still reverberate. Sure, global markets have rallied back strongly. Bullish news, analysis and sentiment have followed suit, as they do. The poor bears have again been bullied into submission, as the punchy bulls have somehow become further emboldened. The optimists are even more deeply convinced of U.S., Chinese and global resilience (the 2008 crisis “100-year flood” view). Fears of China, EM and global tumult were way overblown, they now contend. As anticipated, global officials remain in full control. All is rosy again, except for the fact that global central bankers behave as if they’re utterly terrified of something…..continue reading HERE