This brief article will explain why the world’s banking system is unsound, and what differentiates a sound from an unsound bank. I suspect not one person in 1,000 actually understands the difference. As a result, the world’s economy is now based upon unsound banks dealing in unsound currencies. Both have degenerated considerably from their origins.

Modern banking emerged from the goldsmithing trade of the Middle Ages. Being a goldsmith required a working inventory of precious metal, and managing that inventory profitably required expertise in buying and selling metal and storing it securely. Those capacities segued easily into the business of lending and borrowing gold, which is to say the business of lending and borrowing money.

Most people today are only dimly aware that until the early 1930s, gold coins were used in everyday commerce by the general public. In addition, gold backed most national currencies at a fixed rate of convertibility. Banks were just another business—nothing special. They were distinguished from other enterprises only by the fact they stored, lent, and borrowed gold coins, not as a sideline but as a primary business. Bankers had become goldsmiths without the hammers.

Bank deposits, until quite recently, fell strictly into two classes, depending on the preference of the depositor and the terms offered by banks: time deposits, and demand deposits. Although the distinction between them has been lost in recent years, respecting the difference is a critical element of sound banking practice.

Time Deposits. With a time deposit—a savings account, in essence—a customer contracts to leave his money with the banker for a specified period. In return, he receives a specified fee (interest) for his risk, for his inconvenience, and as consideration for allowing the banker the use of the depositor’s money. The banker, secure in knowing he has a specific amount of gold for a specific amount of time, is able to lend it; he’ll do so at an interest rate high enough to cover expenses (including the interest promised to the depositor), fund a loan-loss reserve, and if all goes according to plan, make a profit.

A time deposit entails a commitment by both parties. The depositor is locked in until the due date. How could a sound banker promise to give a time depositor his money back on demand and without penalty when he’s planning to lend it out?

In the business of accepting time deposits, a banker is a dealer in credit, acting as an intermediary between lenders and borrowers. To avoid loss, bankers customarily preferred to lend on productive assets, whose earnings offered assurance that the borrower could cover the interest as it came due. And they were willing to lend only a fraction of the value of a pledged asset, to ensure a margin of safety for the principal. And only for a limited time—such as against the harvest of a crop or the sale of an inventory. And finally, only to people of known good character—the first line of defense against fraud. Long-term loans were the province of bond syndicators.

That’s time deposits. Demand deposits were a completely different matter.

Demand Deposits. Demand deposits were so called because, unlike time deposits, they were payable to the customer on demand. These are the basis of checking accounts. The banker doesn’t pay interest on the money, because he supposedly never has the use of it; to the contrary, he necessarily charged the depositor a fee for:

- Assuming the responsibility of keeping the money safe, available for immediate withdrawal, and

- Administering the transfer of the money if the depositor so chooses by either writing a check or passing along a warehouse receipt that represents the gold on deposit.

An honest banker should no more lend out demand deposit money than Allied Van and Storage should lend out the furniture you’ve paid it to store. The warehouse receipts for gold were called banknotes. When a government issued them, they were called currency. Gold bullion, gold coinage, banknotes, and currency together constituted the society’s supply of transaction media. But its amount was strictly limited by the amount of gold actually available to people.

Sound principles of banking are identical to sound principles of warehousing any kind of merchandise, whether it’s autos, potatoes, or books. Or money. There’s nothing mysterious about sound banking. But banking all over the world has been fundamentally unsound since government-sponsored central banks came to dominate the financial system.

Central banks are a linchpin of today’s world financial system. By purchasing government debt, banks can allow the state—for a while—to finance its activities without taxation. On the surface, this appears to be a “free lunch.” But it’s actually quite pernicious and is the engine of currency debasement.

Unsound Banking

Fraud can creep into any business. A banker, seeing other people’s gold sitting idle in his vault, might think, “What is the point of taking gold out of the ground from a mine, only to put it back into the ground in a vault?” People are writing checks against it and using his banknotes. But the gold itself seldom moves. A restless banker might conclude that, even though it might be a fraud on depositors (depending on exactly what the bank has promised them), he could easily create lots more banknotes and lend them out, and keep 100% of the interest for himself.

Left solely to their own devices, some bankers would try that. But most would be careful not to go too far, since the game would end abruptly if any doubt emerged about the bank’s ability to hand over gold on demand. The arrival of central banks eased that fear by introducing a lender of last resort. Because the central bank is always standing by with credit, bankers are free to make promises they know they might not be able to keep on their own.

How Banking Works Today

In the past, when a bank created too much currency out of nothing, people eventually would notice, and a “bank run” would materialize. But when a central bank authorizes all banks to do the same thing, that’s less likely—unless it becomes known that an individual bank has made some really foolish loans.

Central banks were originally justified—especially the creation of the Federal Reserve in the US—as a device for economic stability. The occasional chastisement of imprudent bankers and their foolish customers was an excuse to get government into the banking business. As has happened in so many cases, an occasional and local problem was “solved” by making it systemic and housing it in a national institution. It’s loosely analogous to the way the government handles the problem of forest fires: extinguishing them quickly provides an immediate and visible benefit. But the delayed and forgotten consequence of doing so is that it allows decades of deadwood to accumulate. Now when a fire starts, it can be a once-in-a-century conflagration.

Banking all over the world now operates on a “fractional reserve” system. In our earlier example, our sound banker kept a 100% reserve against demand deposits: he held one ounce of gold in his vault for every one-ounce banknote he issued. And he could only lend the proceeds of time deposits, not demand deposits. A “fractional reserve” system can’t work in a free market; it has to be legislated. And it can’t work where banknotes are redeemable in a commodity, such as gold; the banknotes have to be “legal tender” or strictly paper money that can be created by fiat.

The fractional reserve system is why banking is more profitable than normal businesses. In any industry, rich average returns attract competition, which reduces returns. A banker can lend out a dollar, which a businessman might use to buy a widget. When that seller of the widget re-deposits the dollar, a banker can lend it out at interest again. The good news for the banker is that his earnings are compounded several times over. The bad news is that, because of the pyramided leverage, a default can cascade. In each country, the central bank periodically changes the percentage reserve (theoretically, from 100% down to 0% of deposits) that banks must keep with it, according to how the bureaucrats in charge perceive the state of the economy.

In any event, in the US (and actually most everywhere in the world), protection against runs on banks isn’t provided by sound practices, but by laws. In 1934, to restore confidence in commercial banks, the US government instituted the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) deposit insurance in the amount of $2,500 per depositor per bank, eventually raising coverage to today’s $250,000. In Europe, €100,000 is the amount guaranteed by the state.

FDIC insurance covers about $9.3 trillion of deposits, but the institution has assets of only $25 billion. That’s less than one cent on the dollar. I’ll be surprised if the FDIC doesn’t go bust and need to be recapitalized by the government. That money—many billions—will likely be created out of thin air by selling Treasury debt to the Fed.

The fractional reserve banking system, with all of its unfortunate attributes, is critical to the world’s financial system as it is currently structured. You can plan your life around the fact the world’s governments and central banks will do everything they can to maintain confidence in the financial system. To do so, they must prevent a deflation at all costs. And to do that, they will continue printing up more dollars, pounds, euros, yen, and what-have-you.

Regards,

Doug Casey

for The Daily Reckoning

P.S. I originally posted this at the International Man, right here.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to sign up for The Daily Reckoning — a free and entertaining look at the world of finance and politics. The articles you find here on our website are only a snippet of what you receive in The Daily Reckoning email edition. Click here now to sign up for FREE to see what you’re missing.

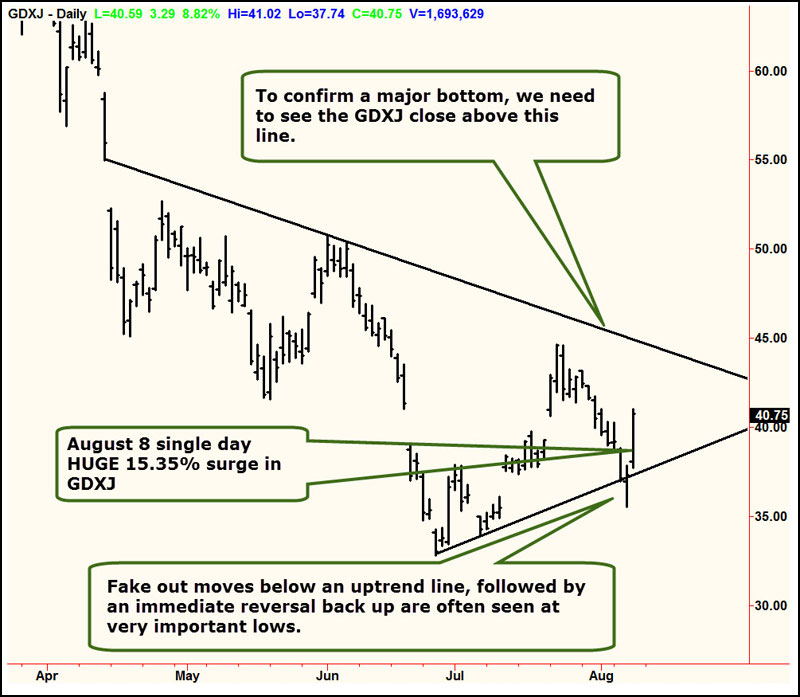

Less than a decade after a housing/derivatives bubble nearly wiped out the global financial system, a new and much bigger commodities/derivatives bubble is threatening to finish the job. Raw materials are tanking as capital pours out of the most heavily-impacted countries and into anything that looks like a reasonable hiding place. So the dollar is up, Swiss and German bond yields are negative, and fine art is through the roof.

Less than a decade after a housing/derivatives bubble nearly wiped out the global financial system, a new and much bigger commodities/derivatives bubble is threatening to finish the job. Raw materials are tanking as capital pours out of the most heavily-impacted countries and into anything that looks like a reasonable hiding place. So the dollar is up, Swiss and German bond yields are negative, and fine art is through the roof.

You’re likely thinking that a discussion of “sound banking” will be a bit boring. Well, banking should be boring. And we’re sure officials at central banks all over the world today—many of whom have trouble sleeping—wish it were.

You’re likely thinking that a discussion of “sound banking” will be a bit boring. Well, banking should be boring. And we’re sure officials at central banks all over the world today—many of whom have trouble sleeping—wish it were.

It is a slow day in a little Greek Village . The rain is beating down and the streets are deserted. Times are tough, everybody is in debt, and everybody lives on credit.

It is a slow day in a little Greek Village . The rain is beating down and the streets are deserted. Times are tough, everybody is in debt, and everybody lives on credit.