Bonds & Interest Rates

The blogosphere is rife with talk of the “death of the US Dollar.”

The US Dollar will eventually die, as all fiat currencies do. But the fact remains that it is the reserve currency of the world. And everyone on the planet has been borrowing in US Dollars for decades, or leveraging up using Dollars.

When you borrow in US Dollars you are effectively shorting the US Dollar. So when leverage decreases through defaults or restructuring, the number of US Dollars outstanding diminishes.

And this strengthens the US Dollar.

With that in mind, it looks as though we are in the early stages of a massive, multi-year Dollar deleveraging cycle. Indeed, the greenback is now breaking out against EVERY major world currency.

Here’s the US Dollar/ Japanese Yen:

Here’s the US Dollar/ Euro:

Even the Swiss’ decision to break the peg to the Euro hasn’t stopped the US Dollar from breaking out of a long-term downtrend relative to the Franc:

The fact that we are getting major breakouts of multi-year if not multi-decade patterns against every major world currency indicates that this US Dollar bull market is the REAL DEAL, not just an anomaly.

With that in mind, I continue to believe the US Dollar is in the beginning of a multi-year bull market. And this will result in various crises along the way.

Globally there is over $9 trillion borrowed in US Dollars and invested in other assets/ projects. This global carry trade is now blowing up and will continue to do so as Central Banks turn on one another.

This will bring about a wave of deleveraging that will see the amount of US Dollars in the system shrink. This in turn will drive the US Dollar higher.

Indeed, consider that the US Dollar actually MATCHED the performance of stocks for the year of 2014.

Any entity or investor who is using aggressive leverage in US Dollars will be at risk of imploding. Globally that $9 trillion in US Dollar carry trades is equal in size to the economies of Germany and Japan combined.

Smart investors are preparing now.

Just as the steady torrent of awful economic data, which began in the First Quarter and continued well into April and May, had forced many market analysts to grudgingly concede that 2015 would not see the robust economic growth that most had expected, the statisticians arrived on the scene like a cavalry charge and routed the forces of pessimism with a wave of their spreadsheets.

The campaign began in late April with some seemingly groundbreaking analysis by CNBC’s Steve Liesman showing that over a 30 year time frame GDP data had consistently measured first quarter growth at 1.87%, which was far lower than the 2.7% rate averaged in the following three quarters of the year. He pointed out that the trend had gotten even more pronounced since 2010, when first quarter growth averaged just .62% and the remaining three quarters averaged 2.3%. The disparity caused Liesman, and others, to question whether first quarter data should be regarded as reliable.

The problem hinges on the efficacy of the ‘seasonal’ adjustments that are baked into the GDP methodology. These filters are designed to smooth out the changes in spending, production, and consumption that occur over the course of the year. After all, business and consumers behave differently in December than they do in July.

When Liesman pressed the Bureau of Economic Analysis (the government entity that supplies the data) to explain his findings, the agency responded “BEA is currently examining possible residual seasonality in several series, which may lead to improvements in…the regular annual revision to GDP.” We should understand “improvements” to mean changes that make first quarter GDP higher. A few weeks later the BEA provided some specifics saying methods for counting government defense spending and “certain inventory investment series” could be improved to help address the distortion. It promised to correct these deficiencies by July 30. It promised to correct these deficiencies by July 30. But to make sure that everyone understood that the help was definitely on the way, the BEA issued a blog post on May 22 in which it specified a number of areas in which it will eliminate what it calls “residual seasonality.” This term should be accurately defined as “areas that we think should be higher.”

As if on cue, the Federal Reserve itself waded into the debate with its own new study (released by the San Francisco Fed – Janet Yellen’s former stomping grounds) that seemed to confirm and expand on Liesman’s analysis and the BEA’s concessions (makes one wonder if these campaigns are coordinated). Fed economists took a hard look at the disappointing .2% annualized first quarter 2015 growth, and determined that the seasonal adjustments that have been in use for years were insufficient to fully reveal the true health of the economy. When the San Francisco Fed added a second level of seasonal adjustments, it determined that Q1 growth should have been measured at 1.8% annualized. While that growth rate would not be considered strong, it is much closer to the 2.7%-3.0% that most forecasters had predicted at the end of 2014. No matter that the Atlanta Fed’s “GDP Now,” which was designed to be a more objective and contemporaneous measurement tool, was confirming near zero growth in Q1, many economists and media outlets jumped on the Fed study as proof positive that the economy is stronger than the pessimists portray.

In reality, few people actually understand how the complex and opaque seasonal adjustments really work (I know I don’t). Fewer still have the patience to wade through the formulas to determine inefficiencies and potential remedies. This provides the statisticians with a good deal of convenient refuge against critics. But it’s important to realize that unlike straight GDP measurement, which is ideally a strict accounting of spending, these adjustments can introduce an element of subjective institutional bias.

Government entities (and to a lesser extent media outlets) have many reasons to suggest that the economy is better than it really is. The Fed wants us to believe that its policies are effective; the Federal government wants us to believe that the economy is healthy, and financial media outlets depend on confident investors. I’m not saying that these biases are insidious or conspiratorial, but it does produce an environment where there is more emphasis placed on finding reasons to explain why GDP measurements are low, than there is to find reasons why it is too high. The subjectivity of the seasonal adjustments gives these biases room to run.

Government entities (and to a lesser extent media outlets) have many reasons to suggest that the economy is better than it really is. The Fed wants us to believe that its policies are effective; the Federal government wants us to believe that the economy is healthy, and financial media outlets depend on confident investors. I’m not saying that these biases are insidious or conspiratorial, but it does produce an environment where there is more emphasis placed on finding reasons to explain why GDP measurements are low, than there is to find reasons why it is too high. The subjectivity of the seasonal adjustments gives these biases room to run.

People understand that holiday spending juices GDP at the end of the year, and that post-holiday depletion and cold winters cause consumers to retrench. This causes them to try to compensate for the weakness in the first quarter. But there is no pressure for them to find reasons that GDP may be too high in December and May (when Christmas lists and pleasant weather should be encouraging shopping).

Given that, why do we really need seasonal adjustments in the first place? Yes December is different from July, but those differences persist every year. If we are looking at full year GDP, which is the measure that everyone is really after, why not keep a cumulative tally that we compare to prior years rather than prior quarters? Wouldn’t this strip out a needless and opaque system of adjustments from a measurement system that is already overly complex to begin with? I believe the truth is the system is getting more complex because we want it that way. We prefer the ability to manipulate figures rather than allowing the figures to tell us things that we don’t want to hear.

The real disconnect lies in the failure of the economy to grow, as most people assumed that it would, after the Fed’s quantitative easing and zero interest rates had supposedly worked their magic. But as I have said many times before, these policies act more as economic depressants than they do as stimulants. As long as these monetary policies persist, our economy will never return to the growth rates that would be considered healthy.

In any event, many market watchers are grabbing at the San Francisco Fed report to conclude that Janet Yellen will raise rates this year, despite the weakness that the unadjusted GDP reports indicate. Such a conclusion is premature. I believe that the Fed wants us to think that the economy is strong, in the hopes that perception may one day soon become reality. If people think the economy is strong their optimism could influence their spending, hiring, and investing decision. As a result, optimistic Fed pronouncements should be considered just another policy tool; call it “open mouth operations.” But I do not believe the Fed has any actual intention of delivering the rate increases that it may expect will damage our already weak economy.

Just as ultra-low interest rates start to seem normal, the markets decide otherwise. US 10-year Treasury bonds yielded about 1.9% in April and are now above 2.20%:

And the trend reversal isn’t limited to the US. Across Europe and Asia rates have spiked in the past month. From Bloomberg:

What does this mean? Several things, potentially:

1) Markets tend to reverse when everyone finally accepts that the dominant trend is going to continue. This could be one of those times, as negative rates came to be accepted as inevitable and (for a growing number of deluded statists) actually good, leading traders to anticipate more of the same. In other words, the trade got too crowded.

2) Investors might be losing faith in governments’ ability to maintain the value of even strong currencies like the dollar and Swiss franc, which would make negative-yield bonds double losers. To which one can only respond, “really, you just figured that out??”

3) All the talk of making cash illegal led a critical mass of people to consider the implications and conclude that such a world is not one in which they want to live.

4) It means nothing, just a hiccup in a dominant secular trend that will take interest rates into sharply negative territory world-wide and result in a cashless society where central banks have unfettered ability to peg interest rates, equity prices and pretty much everything else wherever they want.

Is the debt bomb about to go off?

Editor’s note: You’ll find the text version of the story below the video.

The yields on U.S. Treasuries and European sovereign debt have risen sharply in a relative short time.

Bond prices trend inversely to yields — which means debt portfolios have suffered substantial losses.

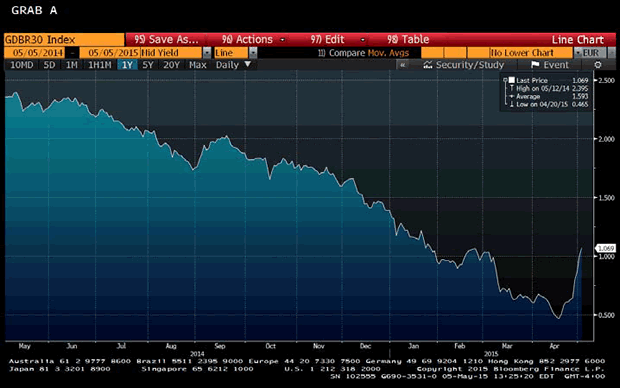

From mid-April through May 6, yield on German 10-year bunds spiked 47 basis points. Yields on 10-year U.S. Treasuries jumped 29 basis points in just the past week.

Volatility in the bond market continued on May 7. In just a few hours, the yield on the 10-year bund jumped 21 basis points before pulling back. Bear in mind that sovereign bond yields rarely move more than a fraction of one percent in a day.

Long-term bonds have been hit particularly hard. The yield on 30-year U.S. Treasuries topped 3% for the first time this year.

“We’ve been hurt,” said [an] investment manager at Aberdeen Asset Management. “The movements of recent days have been extremely unusual ….” (Financial Times, May 7)

German government debt is regarded as a benchmark for European assets.

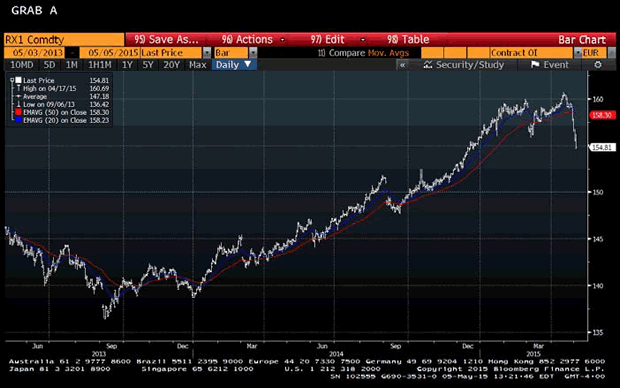

Take a look at this chart of Euro-Bund futures from our May 6 Financial Forecast Short Term Update:

Similar to the credit crisis in 2007-2009, the rout is starting in the bond market, where the pace of evaporating liquidity is quickening. Bids are pulled, prices crack, yields rise and it leaks out toward other asset classes. The turn in bonds in the U.S. and Europe is a sign that the “debt bomb” … is about to go boom.

The April Elliott Wave Financial Forecast warned subscribers about the insanity that pervades the world’s bond markets. Take a look at this chart and commentary:

Many bonds that are perceived to be the safest credit risks guarantee investors a loss. To our knowledge this has never occurred on such a widespread basis in the history of finance. Yields on nearly a third of the euro area’s $6 trillion of government bonds are below zero, which means that bond buyers are guaranteed to lose money if they buy these bonds and hold them to maturity.

The risk of widespread defaults also lurks in the world’s credit markets.

Here’s what well-known hedge fund manager Stanley Drunkenmiller recently said:

Back in 2006/2007, 28% of debt being issued was B-rated. Today 71% of the debt that’s been issued in the last two years is B-rated. So, not only have we issued a lot more debt, we’re doing so with much [lower standards].

All told, the world’s credit markets are on very unstable ground. Expect that ground to get even shakier in the months ahead.

This article was syndicated by Elliott Wave International and was originally published under the headline Big Volatility Shakes Bond Investors. EWI is the world’s largest market forecasting firm. Its staff of full-time analysts led by Chartered Market Technician Robert Prechter provides 24-hour-a-day market analysis to institutional and private investors around the world.

The old saying is that a “Get me in!” bond market is always followed by a “Get me out!” event. In shorter form, it is GMI! followed by GMO!.

This was the case with the price of the US Treasury soaring to an Upside Exhaustion at the end of January. Our special study of January 20th, titled “Ending Action”, reviewed the probability that this could be the end of the great bull market that began in 1981 when the long-dated yield was 15%.

Our Pivot of April 9th noted that the reversal would be a global event and that the “European Central Bank is full of unsupportable positions”. Our April 22 comment was that the loss of liquidity in the US market could be “Tied to an equally significant loss in global [bond] markets”.

More specifically, the reversal in spreads that could be accomplished by June could be as “interesting” as the one in 1998 that took down LTCM.

The Eurobond Future set its high at 160.69 on April 17 and the break to today’s 154 level shows some intense “GMO!”. Technically and within this the German 30-year bond price registered an Upside Exhaustion. Of importance is that the bull move from September 2013 was confirmed by a positive crossover on two key moving averages. These provided support on the way up and have been decisively taken out this week. A negative crossover is being accomplished now.

Eurobond Future

The chart of the German Ten-Year Yield puts the reversal in perspective.

Much has been said about nominal rates declining to less than zero. This as it turns out was providing short sellers a very low “carry”.

Adjusted for CPI inflation real interest rates during a financial mania record a distinctive decline. That’s in the senior currency. Sometimes to negative levels, as with the 1873 Bubble. In 2007 it declined to minus 1.5%. This increased by 6 percentage points in the 2008 Crash.

With the CPI rate at close to zero during the first quarter, the low for the real rate was close to 2 percent. Now it is approaching 3 percent.

The typical increase in a post-bubble contraction has been 12 (no typo) percentage points. It has been Mother Nature’s way of ending compulsive expansion and abuse of credit, otherwise known as a financial mania. A huge increase in real rates for global government debt seems inevitable. In which case, the long experiment in artificially lowering rates by policy adventurers would come to an end.

Those who analyze major financial setbacks as policy errors or random accidents, have described them as a “Minsky Moments” or a “Black Swans”. A review of the greatest crashes in history concludes that they have been setup by speculative excess, which is technically measurable. On the stock market part of a bubble, the peak has been anticipated by a distinctive changes in credit spreads and the yield curve. On all six examples since the first in 1720, there has been a reliable seasonal component.

Forget “Minsky “and “Black Swans”, this is central bankers discovering a “Get Me Out!” moment.