Bonds & Interest Rates

As the world continues to digest breaking news out of Greece, today the Godfather of newsletter writers, 90-year old Richard Russell, discussed what central banks don’t want you to know about a $199 trillion nightmare. Russell also discussed what this will mean for the gold and silver markets.

As the world continues to digest breaking news out of Greece, today the Godfather of newsletter writers, 90-year old Richard Russell, discussed what central banks don’t want you to know about a $199 trillion nightmare. Russell also discussed what this will mean for the gold and silver markets.

….continue reading HERE

Last week a scene unfolded in Athens, largely unnoticed by American eyes, that provided all the visual and metaphorical symbols needed to define the current state of the global economy. Hollywood’s best screenwriters couldn’t have laid it out any better.

Last week a scene unfolded in Athens, largely unnoticed by American eyes, that provided all the visual and metaphorical symbols needed to define the current state of the global economy. Hollywood’s best screenwriters couldn’t have laid it out any better.

Tiring of being told by self-righteous foreigners to pay for past borrowing with current austerity, the Greek people had just elected the most radically left-wing government in recent memory, whose stated goal was to tell their creditors that they were not going to take it anymore. The leadership of the victorious Syriza Party, a collection of mostly young Marxist and Trotskyite academics, had promised the Greek people a clean break from the past and an end to years of economic malaise. Although their plan seemed fundamentally contradictory (telling foreign creditors to butt out even while courting more aid), Syriza nonetheless appealed to a frustrated electorate through their dynamism and optimism.

To show that they were not just another upstart coalition that would co-opt the status quo once elected, Syriza leaders adopted the posture, vocabulary and clothing of revolutionaries. Throughout his campaign, Alex Tsirpas, the new prime minister, refused to wear a tie, thereby eschewing the most potent symbol of traditional power. When sworn in as prime minister, also with an open collar, he dispensed with the “hand on the bible” ceremony and instead invoked the spirit of fallen Greek Marxists. Since the election Syriza leaders have hot toned down their rhetoric as many predicted they would. Could it be that they actually meant what they said?

Syriza’s fiery attitude has put Greece on a collision course with northern European leaders who face the political necessity of requiring Greece to repay previously delivered bail out money. In this context the first meeting between Yanis Varoufakis, the newly installed Greek Finance minister and Jeroen Dijsselbloem the Dutch representative of the so-called “troika” of lenders (The European Central Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the European Commission), was bound to produce some drama. The meeting exceeded expectations on that front. But how it looked was perhaps more important than what was said.

In a room packed with cameras and reporters, Varoufakis strode in not just tieless and open collared, but with his shirt shockingly untucked. He ambled to his chair, and sat slouching backwards with his legs crossed like a poker player barely able to contain the glee of a winning hand. His expressions were effusive, satirical, and defiant. All he lacked were sunglasses and a couple of groupies to complete the rock star persona. To his right sat the stiff necked, buttoned-down Dutchman, who in the words of Colonel Kurtz appeared like “an errand boy, sent by grocery clerks, to collect a bill.”

The two agreed on seemingly nothing. Dijsselbloem insisted that the new Greek government live up to the austerity and repayment commitments, and Varoufakis said that the Greeks would no longer negotiate with the creditors who he believed were responsible for his country’s destitution. When there was really nothing left to say, the meeting came to an abrupt end and the two executed a painfully awkward handshake. Dijsselbloem, seeming annoyed, avoided eye contact with his counterpart and left the room without looking back. On the other hand, Varoufakis, seemingly enjoying the moment, shrugged his shoulders and smiled for the cameras, as if to say “What’s up with the stuffed shirt?”

What could explain these contrasting attitudes? Shouldn’t the creditor, the one lending the money, and the party who will be asked for more, be in the power position? Shouldn’t the borrower be in position of supplication? If you thought that, you don’t understand the current way of the world. Based on the ascendancy of Keynesian “demand side” economics it is the borrower who is considered the key driver of growth. The theory holds that if the borrower stops borrowing they will also stop spending. When that happens they believe the entire economy collapses, dragging down both lenders and borrowers in the process. From that perspective, the bigger the borrower the greater his importance, and the more leverage he has with the lender. This is like the old adage: “If you owe the bank $10, that’s your problem. But if you owe the bank $10 million dollars, that’s the bank’s problem.”

Syriza knows that northern European leaders are terrified at the prospect of disintegration of the EU and the stability it provides. The goal of maintaining open and essentially captive markets for German manufacturers was the prime reason that pried open Berlin’s wallet in the first place. But Syriza also understands the power that debtors have in today’s world. Default leads to liquidations, which in turn leads to deflation, the biggest bugaboo in the Keynesian night gallery of economic fears. After years of bailouts of banks, corporations, and governments, debtors know that no one is ready to risk another Lehman Brothers type collapse on any level. The bar of “Too Big to Fail” has gotten progressively lower. If Greece can repudiate its debts, the temptation for larger indebted nations like Italy and Spain to do the same will be ever greater.

This understanding fuels not only the swagger of the Greek finance minister but also the attitude of the world’s largest debtor, the United States of America. Although the $1 Trillion dollar plus annual budget deficits have been cut significantly in recent years (thought the national debt has exploded beyond $18 trillion), I believe the reduction is largely a function of the asset bubbles that have been engineered by the Fed’s six year program of quantitative easing and zero percent interest rates. Any sustained economic downturn could immediately send the red ink back into record territory. But flush with his victory speech/State of the Union address, President Obama has adopted a bit of the Varoufakis bravado.

President Obama’s newly unveiled 2015 budget includes almost $500 billion in new spending; effectively dispensing with the token austerity that Washington had imposed on itself with the 2011 “Sequester.” In my opinion, the U.S. has virtually no hope of paying for all of our spending through taxation, the budget busting proposals should be viewed as a message to our foreign creditors that we plan on borrowing plenty more, and that we expect that they will keep lending for as long as we want. From a global economics perspective the United States is like Greece writ very, very large. Much like the Northern European countries, the major exporting nations around the world are terrified that their economies would be shut out of U.S. markets if their currencies were to strengthen against the dollar. I believe this has allowed America to approach its finances with impunity.

But this confidence may be leading to trouble. If the new Greek government keeps following its current course, it may ultimately be shown the door of the Eurozone. Although a “Grexit” may ultimately pave the way for a real Greek recovery, the Greeks themselves should have no illusions about how painful this journey may be. Without the purchasing power of the euro and the largesse of the creditors supporting them, the Greeks may find themselves with a basket case currency that delivers far lower living standards. If Greek government employees thought austerity was bad when it was imposed from Brussels, wait until they see how bad it’s going to be when imposed by Athens. In fact, no Greek recovery will be possible until the newly elected Marxists become unapologetic capitalists.

When the Swiss National Bank decided to abruptly reverse course on its euro peg, the world should have been treated to a fresh lesson at the finite nature of creditor patience. While this message may have been lost on most observers, sooner or later this reality will sink in. When it does, the shirts will be tucked, the ties will be fastened, and knees just may start bending.

The Chinese Year of the Ram will kick off at the end of this month, but for now it looks as if 2015 will be the Year of the Central Banks.

I spend a lot of time talking about gold, oil and emerging markets, and it’s important to recognize what drives these asset classes’ performance. Government and fiscal policy often have much to do with it. But in the past three months, we’ve seen central banks take center stage to engage in a new currency war: a race to the bottom of the exchange rate in an attempt to weaken their own currencies and undercut competitor nations.

Indeed, amid rock-bottom oil prices, deflation fears and slowing growth, policymakers from every corner of the globe are enacting some sort of monetary easing program. Last month alone, 14 countries have cut rates and loosened borrowing standards, the most recent one being Russia.

A weak currency makes export prices more competitive and can help give inflation a boost, among other benefits.

“The U.S. seems to be the only country right now that doesn’t mind having a strong currency,” says John Derrick, Director of Research here at U.S. Global Investors.

Since July, major currencies have fallen more than 15 percent against the greenback.

Two weeks ago, Switzerland’s central bank surprised markets by unpegging the Swiss franc from the euro in an attempt to protect its currency, known as a safe haven, against a sliding European bill. Its 10-year bond yield then retreated into negative territory, meaning investors are essentially paying the government to lend it money.

This and other monetary shifts have huge effects on commodities, specifically gold. As I told Resource Investing News last week:

Gold is money. And whenever there’s negative real interest rates, gold in those currencies start to rise. Whenever interest rates are positive, and the government will pay you more than inflation, then gold falls in that country’s currency. Last year, only the U.S. dollar had positive real rates of return. All the other countries had negative real rates of return, so gold performed exceptionally well.

Other countries whose central banks have enacted monetary easing are Canada, India, Turkey, Denmark and Singapore, not to mention the European Central Bank (ECB), which recently unveiled a much-needed trillion-dollar stimulus package.

A recent BCA Research report forecasts that as a result of quantitative easing (QE), a weak euro and low oil prices, the eurozone should grow “by about 2 percentage points over the next two years, taking growth from the  current level of 1 percent to around 3 percent. This is well above the range of any mainstream forecast.” The report continues: “[European] banks, in particular, are likely to outperform, as they will be the direct beneficiaries of rising credit demand, falling default rates and the ECB’s efforts to reflate asset prices.” This bodes well for our Emerging Europe Fund (EUROX), which is overweight financials.

current level of 1 percent to around 3 percent. This is well above the range of any mainstream forecast.” The report continues: “[European] banks, in particular, are likely to outperform, as they will be the direct beneficiaries of rising credit demand, falling default rates and the ECB’s efforts to reflate asset prices.” This bodes well for our Emerging Europe Fund (EUROX), which is overweight financials.

Speaking of oil, the current average price of a gallon of gas, according to AAA’s Daily Fuel Gauge Report, is $2.05. But in the UK, where I visited last week, it’s over $6. That’s actually down from $9 in June. You can see why Brits don’t drive trucks and SUVs.

But that’s the power of currencies. As illustrated by the clever image of a Chinese panda crushing an American eagle, China’s economy surpassed our own late last year, based on purchasing-power parity (PPP).

Financial columnist Brett Arends puts it into perspective just how huge this development really is: “For the first time since Ulysses S. Grant was president, America is not the leading economic power on the planet.”

Financial columnist Brett Arends puts it into perspective just how huge this development really is: “For the first time since Ulysses S. Grant was president, America is not the leading economic power on the planet.”

An easier way to comprehend PPP is by using The Economist’s Big Mac Index, a “lighthearted guide to whether currencies are at their ‘correct’ level.” The index takes into account the price of McDonald’s signature sandwich in several countries and compares it to the price of one here in the U.S. to determine whether those currencies are undervalued or overvalued. A Big Mac in China, for instance, costs $2.77, suggesting the yuan is undervalued by 42 percent. The same burger in Switzerland will set you back $7.54, making the franc overvalued by 57 percent.

Earning More in a Low Interest Rate World

From what we know, the Federal Reserve is the only central bank in the world that’s considering raising rates sometime this year, having ended its own QE program in October.

Last month we learned that the Consumer Price Index (CPI), or the cost of living, fell 0.4 percent in December, its biggest decline in over six years. We’re not alone, as the rest of the world is also bracing for deflation:

Following Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s announcement last Wednesday, the bond market rallied, pushing the 10-year yield to a 20-month low.

Following Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s announcement last Wednesday, the bond market rallied, pushing the 10-year yield to a 20-month low.

Interest rates remain at historic lows, where they might very well stay this year. But when they do begin to rise—whenever that will be—shorter-term bond funds offer more protection than longer-term bond funds. That’s basic risk management. We always encourage investors to understand the DNA of volatility. Every asset class has its own unique characteristics. For example:

Our Near-Term Tax Free Fund (NEARX) invests in shorter-term municipal bonds, thereby taking off some of the risk if the Fed decides to raise rates this year. We’re very proud of this fund, as it’s delivered 20 years of consistent positive returns. Among 25,000 equity and bond funds in the U.S., only 30 have achieved the feat of giving investors positive returns for the same duration, according to Lipper.

That equates to a rare 0.1 percent, roughly the same probability that your son or grandson will be drafted into the NFL and play in the Super Bowl.

In the past 30 years, we’ve experienced massive volatility in both the equity and bond markets, and we’re thrilled for our shareholders that we’ve been able to deliver such a stellar product, under the expert management of John Derrick. What’s more, NEARX continues to maintain its coveted 5-star overall rating from Morningstar, among 173 Municipal National Short-Term funds as of 12/31/2014, based on risk-adjusted return. If you are in Orlando next week, come by the World Money Show to hear John talk about the fund’s history of success. The event is free and my team would love to meet you at booth 514.

Upcoming Webcast

To those who listened in on our last webcast, “Bad News Is Good News: A Contrarian Case for Commodities,” we hope you enjoyed it and received some good, actionable insight. If you weren’t able to join us, you can watch the webcast at your convenience on demand. Our next webcast is coming up February 18 and will focus on emerging markets, China in particular. We hope you’ll join us! We’ll be sharing a registration link soon.

Please consider carefully a fund’s investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses. For this and other important information, obtain a fund prospectus by visiting www.usfunds.com or by calling 1-800-US-FUNDS (1-800-873-8637). Read it carefully before investing. Distributed by U.S. Global Brokerage, Inc.

Heading into the last trading day of January with the futures marked down 1% and I think it is safe to say that we will have a down month, with the potential for a 3% loss.

Heading into the last trading day of January with the futures marked down 1% and I think it is safe to say that we will have a down month, with the potential for a 3% loss.

…..continue reading HERE

The Central Banks of Switzerland, Canada and the EU have rocked the markets…but the most important question in Central Bank land is, ”Will the Fed still raise interest rates in 2015?” Our view has been that global Central Banks…despite all their “money printing”… are losing the fight against deflation…that “Currency Wars” are just passing the “hot potato” of deflation from one country to another. In his famous (helicopter money) speech in November 2002 Ben Bernanke defined deflation as a “Collapse in demand.” Well crude oil, copper and the major commodity indices, as well as CAD and the AUD are at 6 year lows…and as Dennis Gartman likes to say, “When a market is going down you have no idea how far down, down is!”

Whether or not the Fed will raise interest rates is the KEY question because the assumed “Divergence” between America and the Rest of the World has helped drive the US Dollar Index to 12 year highs. If the market begins to think that the Fed will not raise rates…for all the obvious reasons…then we’d expect to see a USD correction.

US Dollar Index:

Canadian Dollar: is down ~25% since the commodity boom peaked out in 2011…it’s down ~15% since July 2014…when Crude began its waterfall decline. Last week…before the Bank of Canada cut interest rates…the market was pricing in a 20% chance of an interest rate cut in 2015…it’s now pricing in a 50% chance of ANOTHER interest rate cut in 2015. Pressure on CAD rises exponentially the more Crude Oil falls….BUT…

The Bank of Canada action helped drive the Toronto Stock Index 500 points higher…and drive the Canadian 10 year bond to All Time Highs…

The ECB action has helped drive the German DAX and the German 10 year bond to All Time Highs…

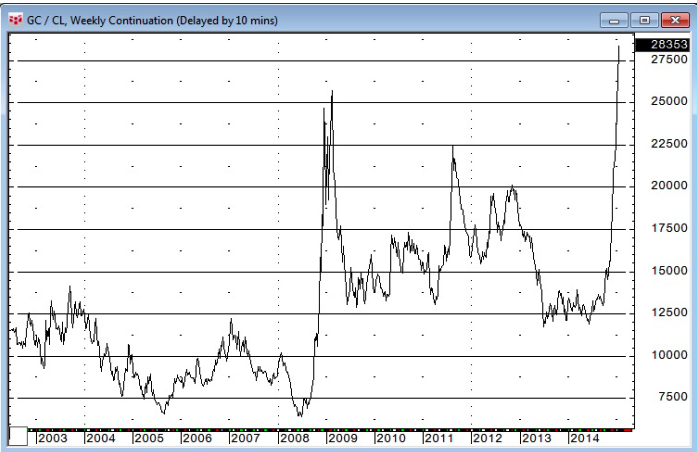

Gold: is up ~$170 (15%) from 4 year lows made last November…gold share indices are up ~30%…as higher gold and lower oil dramatically improve the leverage for gold miners. Last July it took only 12 barrels of WTI to buy 1 ounce of gold…it now takes 28 barrels. Another “consequence” of global deflation and a surging US Dollar may be that “Resource Nationalism” will, by necessity, become a thing of the past…thereby making it easier and cheaper for gold mining companies to operate in many formerly “difficult” countries.

Short term trading: The best results in our Model account YTD have come from short call positions in CAD and AUD. Our worst results came from short OTM puts on the CAD after it had fallen more than 3 cents in 2 weeks…after option vol had surged to 3 year highs and as crude oil looked like it was “stabilizing” around $47…BUT…we hadn’t expected the Bank of Canada to drive CAD to 6 year lows. It “feels” like we should have made good profits this month given the market action…but we are grateful we didn’t get clobbered by some of those same moves!

Long term trading: I’ve made more money over the last 3 – 4 years from my long term hedges against the CAD than from all of my short term trading. I’m especially grateful that I was able to buy more USD last fall…it was hard to do because CAD had dropped below 90 cents and I was selling new lows…but I was able to take the perspective that the ten year “Commodity boom” was over…and the “Big Risk” was that CAD might take out the 2009 lows.