Currency

Extend and Pretend

Extend and Pretend

Now that President Obama has been re-elected, the media is finally free to focus on something besides the clueless undecided voters in Ohio, Florida, and Colorado. The brightest and shiniest object that has attracted its attention is the “fiscal cliff” that we are expected to drive over at the end of the year unless Congress and the President can agree to turn the wheel or apply the brakes.

Fresh from his victory, the President took time today to let the nation know how he proposes to avoid the cliff: to raise taxes on those Americans who make more than $250,000 per year. He made clear that no one making less than that will be asked to pay any more. The two percent of taxpayers that the President is targeting earn 24.1% of all income and pay 43.6% (as of 2008) of all personal federal income taxes. Sounds like a fair share to me. But the four or five percent tax increases on those earners that are being proposed would only yield around $30 to $40 billion per year in added revenue, a drop in the federal bucket. Even if they were to double the amount that they pay our deficit would only be cut by about one third (even if those increases did not trigger an economic slowdown).

So what exactly is this looming menace, and why is it so dangerous? Stripped of its rhetorically charged language the fiscal cliff is simply a legal trigger that will trim the deficit in 2013 by automatically implementing spending cuts and tax increases. In other words, the government will spend less, and more of what it does spend will be paid for with taxes rather than debt. Isn’t this exactly what both parties, and the public, more or less want? The fiscal cliff means that the federal budget deficit will be immediately cut in half, shrinking to approximately $641 billion in 2013 from the approximately $1.1 trillion in 2012. What is so terrible about that? I would argue that there is a greater danger in avoiding the cliff than driving over it.

If you recall, the cliff was created by a deal last year when Congress couldn’t find ways to trim the deficit in exchange for raising the debt ceiling. When they failed to reach an agreement, Congress knew they had to raise the debt ceiling anyway. The resulting Budget Control Act of 2011, signed in August of that year, offered the pretense that they were dealing with our long-term fiscal crisis and not simply raising the debt ceiling with no strings attached. This was done not only to appease some House Republicans, who had threatened to vote against a debt ceiling increase, but to satisfy the bond rating agencies that had threatened a down-grade if Congress failed to act.

Now the focus turns to how Congress will dismantle the structure it created just 16 months ago. There can be little doubt that they will as economists are assuring politicians that driving over the fiscal cliff will immediately bring on a recession. The expiration of the Bush era tax cuts for all taxpayers will cost Americans an estimated $423 billion in 2013 alone. Hundreds of billions of across the board spending cuts, including the military, have been delineated. No politician would allow that to happen.

It is amazing that members of Congress can keep a straight face as they claim to want to address our long-term deficit problem while simultaneously working to avoid any substantive action. No doubt an agreement will be reached that will replace the looming fiscal cliff with another one farther down the road (which they can easily dismantle before we actually reach the precipice). Will the rating agencies buy this bill of goods a second time? If we lack the political courage to go over this fiscal cliff, why should anyone think we will be able to stomach going over the next one? Especially since each time we delay going over the cliff, we simply increase its future size, making it that much harder to actually go over it.

Many currently believe last year’s S&P downgrade resulted from the same congressional dysfunction that resulted in the fiscal cliff agreement. The truth is that the downgrade would probably have been much greater, and more rating agencies would have likely joined S&P in taking action, had it not been for the fiscal cliff agreement. If further downgrades fail to be issued when the lame duck Congress inevitably comes up with another can kicking deal, then the agencies themselves could lose any remaining credibility. In my opinion, the only explanation for inaction by the rating agencies would be for fear of regulatory retaliation by a vindictive U.S government.

I do not think it is a coincidence that while the banks are suffering a regulatory backlash as a result of their perceived culpability for the mortgage crisis, the credit rating agencies have been relatively untouched. But the credit agencies played a key role in catalyzing the mortgage crisis by giving questionable ratings to the mortgage backed securities. My guess is the government simply does not want to open up that can of worms as similar mistakes are being made with respect to the agencies’ ratings of government debt.

The truth is that regardless of what you call it, going over the fiscal cliff is not the problem, it is part of the solution. Our leaders should construct a cliff that is actually large enough to restore fiscal balance before a real disaster occurs. That disaster will take the form of a dollar and/or sovereign debt crisis that will make this fiscal cliff look like an ant hill.

Quotable

“Oft expectation fails, and most oft where most it promises; and oft it hits where hope is coldest; and despair most sits”

William Shakespeare

Commentary & Analysis

We Remain Long-term Bears on Stocks and Bulls on the Dollar

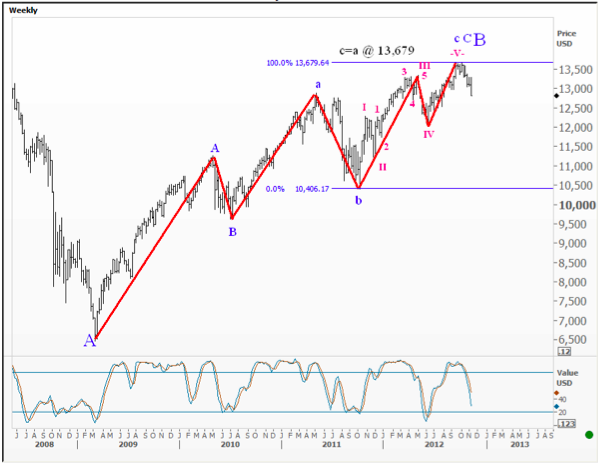

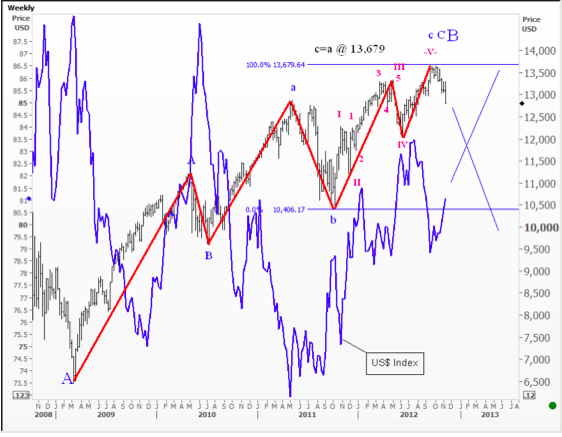

About six-weeks ago, our wave count suggested it was time to get short stocks. We shared the chart below with our Global Investor service Members at the time, suggesting they get short the Dow Jones Industrial Average. So far so good…

We noticed Marc Faber was at it again yesterday, suggesting US stocks should have fallen at least 50% now that the left’s hero is back in the White House.

From my partisan perch, I have seen what President Obama has done to us in four years, so was a bit surprised/shocked/stunned/angry/amazed (insert other words not appropriate for a family publication) he was rewarded with four more to completely finish the job of destroying the US economy. After some reflection yesterday (after I came in from the ledge), I thought about my wife’s grandfather, a real man and proud daily scotch drinker to boot; he used to say to me, “Jack, if the whole world is sane thank God I am crazy.” Now I get it.

On 24 September 2012 we said: Dow Jones Industrial Average Weekly: Symmetry and wave count suggest we may have seen a decent intermediate-term top here in the DJIA:

Same chart above, but fast forward to today:

We don’t believe it’s going too far out on a limb to suggest the US dollar gets a major risk bid should Farber’s view play out along with our chart analysis…

If our assessment about our President’s ability to further destroy real economic growth here is correct, it significantly increases the probability of another major global systemic event. Why? It’s because Europe and Asia need the US to grow, buying time for them to alter their economic models to the new reality of slower global demand. For Europe it is austerity and deflation in periphery country unit labor costs, and in China it is reduced reliance on exports and dangerously high levels of internal investment.

It’s interesting that both Europe and China were routing for President Obama, based on news reports, during the campaign. Well, you know the saying, “Be careful what you wish for it may come true.”

Jack Crooks

Black Swan www.blackswantrading.com

With $7 trilliion in official Forex Reserves owned by emerging, non-members of the G-7 Old Boys Club of global banking elites that’s largely denominated in US$ and Euro, this chart shows the track record of the 5 major currencies reflected by the historic denominator of money…gold.

The Nobel Peace prize committee has made another remarkable choice that boggles the mind. In 2009 they gave it to Obama just for getting elected, and this year its going to the EU – for its role in “uniting the continent,” contributions “to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe.” How ironic that Norway – home of the committee, was one of the few to refuse to join the EU.

The political elites of the US, UK & Europe have flooded the emerging world with their paper in exchange for goods and resources to fuel a virtual industrial revolution in one generation. Those paper holders will ultimately call the shots on the ongoing viability of that paper in due course.

Look at the trends above, or indeed the chart I often show in my talks that takes the same data right back to 1946. That is the track record of ‘currency management’ by the elitist “old boys club”

of the Central Bankers, IMF, BIS and World Bank. For individuals, private ownership of gold is clearly a preferred vehicle for long-term preservation of purchasing power for so long as all the paper issued by the old boys club sports negative real returns.

With a global slump underway, the merging leaders have their hands full at home, and with the US elections now and German election next Spring, they are keeping their heads down to avoid any politically motivated retaliation. But they are taking bilateral steps to settle trade in their own currencies to stem the buildup of their US$ and Euro holdings, which will have big Western consequences down the road.”

Ian McAvity

About Ian McAvity:

“Ian McAvity…he is one of the best technical analysts around.”. I think I saw one of his marvelous, hand-drawn charts in Richard Russell’s Dow Theory Letters, and that led to my subscription to Deliberations. Ian’s timely advice helped me to profitably navigate the gold and gold stock bull market of the 1970s.

Andrew Sarlos

DELIBERATIONS on World Markets, P.O. Box 182, Adelaide St. Station, Toronto, ON M5C 2J1. 1 year, 18 issues, $225. Introductory Trial, 4 issues, $49

The Fiscal Cliff’s Biggest Surprise Could Be a Rising U.S. Dollar.

My grandmother Mimi had a saying that was as blunt as it was uncouth. “When the stuff hits the fan,” she used to say, “it will not be evenly distributed.”

This one came up often when she sensed that world events were about to take a turn for the worse.

You’ve heard me mention Mimi before. She was widowed at a young age and went on to become a savvy global investor long before people thought to look beyond their own backyard.

Mimi never cared what Wall Street’s “Armani Army” had to say.

Instead, she preferred to travel widely to see for herself what the real story was. Having grown up in the midst of the Great Depression, she believed that people were the ultimate indicator and that governments were the penultimate contrarian influence.

If she were still alive today, I think she’d encourage us to take a good hard look in the proverbial “mirror” especially with regard to the looming fiscal cliff making headlines the world over.

And I don’t think she’d waste any time with the doom, gloom and boom crowd either.

She was always on the hunt for opportunity when everyone else was running from chaos. Thanks to her, it’s a habit that remains firmly ingrained in me today.

Not One but Three Fiscal Cliffs

And that brings me back to the “fiscal cliff.”

In my mind, this is a misnomer. There isn’t really a singular fiscal cliff. As I explained earlier this summer to Sheryl Nance of Forbes there are actually three.

- The massive adjustments headed our way as tax and spending cuts expire and come into effect beginning in 2013. You may know it as taxmegeddon.

- The debt debacle and the near complete lack of any sort of credible financial consolidation plan that will affect everything from interest rates to collateral requirements and the US credit rating – again.

- And politicians who simply don’t understand that issues 1 and 2 are already dramatically impacting the economy long before the theoretical limits of spending come into play. Profits are declining and 61% of companies that have reported through Monday October 22nd have failed to meet expectations. Hiring is slowing and top line revenue is increasingly hard to come by.

Together, they constitute a massive threat to the U.S. economy that could push our beleaguered “recovery” to the breaking point. (And I use all the sarcasm I can muster with that because our recovery isn’t anything close to what’s needed.)

Many believe this is a moot point because Congress will get down to business in November after the Presidential Election takes place. The hope is that some sort of budget agreement will be reached and that the US economy will then be positioned for stronger growth in 2013.

Yeah and I suppose the tooth fairy will show up, too.

The IMF and CBO are both on record noting that the estimated $400 – $600 billion in impacts that will result from the combination of spending cuts and tax hikes could derail economic growth while causing a sharp contraction.

Even Helicopter Ben himself has warned of dire consequences. More importantly, dozens of reformed economists, bankers, CEOs and small business owners agree.

Any breakdown in the political infrastructure would represent a catastrophic political, social and economic failure that places literally every level of our economy at risk of further disaster.

Under these conditons, everything from our credit rating to international trading relationships faces mortal risk.

Europe could also come unglued if our banking system goes south. I know many European leaders like to believe they are independent but the reality of an internationally linked fractional banking system renders that notion pure folly in this instance.

Is There a U.S. Dollar Rally Brewing?

Conventional wisdom, under the circumstances, is that the U.S. dollar will become even more worthless than it is now.

I don’t think so. In fact, I expect the U.S. dollar to strengthen significantly. Here’s why…

When the shooting started in the Middle East, bankers came running. When the fiscal crisis began, the dollar ran some more. When the European crisis broke, people couldn’t get enough dollars.

And as China had slowed, the dollar has enjoyed newfound stability. Even during last year’s Congressional debt ceiling donnybrook for example, the dollar outperformed the Euro as investors sought refuge.

History shows that bankers from Shanghai to Milan and all points in between run to the dollar when global instability raises its ugly head and the fiscal cliff or cliffs would certainly constitute instability.

And that reminds me of something else Mimi used to allude to all the time.

“Keith,” she would say as we enjoyed some piping hot pastrami sandwiches and cold beer together (one of her favorites), “much of the world may hate our guts, but when the fur starts flying they love our money.”

These days they have to. For the moment, there’s literally no alternative capable of absorbing the needed liquidity. That alone is probably worth another 10%-15% of upside for the U.S. dollar.

As for the alternatives, the euro itself is in question and at risk of fracture and the yuan isn’t deep enough yet.

As the dollar goes higher, US-based stocks, bonds and preferreds should go along for the ride if not in terms of absolute gains, then in terms of stability. Investors factoring in dividends and bond payments, even at historically low interest rates could enjoy their own recovery.

So, too, could the Chinese who sit on an estimated $3.2 trillion in trade reserves and an estimated $1.169 trillion of which is held in U.S. dollar denominated debt.

Many people don’t want to hear that. But understanding how a stronger U.S. dollar would affect the markets may lead to some the most profitable decisions they’ve made since this crisis began.

Best Regards,

Keith Fitz-Gerald, Chief Investment Strategist

Money Map Press

Further Reading…

Mimi’s sage advice has appeared in Keith’s columns before. In this article, she reasoned that when an investment or a trend began making the rounds over drinks, it was time to move on. In fact, she used to call it the “country club” test. Here, Keith talks about why she’d fire Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer.

Mimi was also mentioned in Keith’s 2009 book entitled: Fiscal Hangover.

I can only pass on Societe Generale’s work to you once in a while, but the piece for today’s Outside the Box is important enough that its author, Dylan Grice, worked hard to convince his bosses to let me share it with you. Dylan is one of my favorite investments analysts, as well as just an all-around nice guy.

In a change from his usual fun-loving demeanor, Dylan issues a serious warning here.

I am more worried than I have ever been about the clouds gathering today (which may be the most wonderful contrary indicator you could hope for…). I hope they pass without breaking, but I fear the defining feature of coming decades will be a Great Disorder of the sort which has defined past epochs and scarred whole generations….

So I keep wondering to myself, do our money-printing central banks and their cheerleaders understand the full consequences of the monetary debasement they continue to engineer?

He runs through some of the Great Debasements of the past, starting with third-century Rome, running through Europe’s medieval inflations and the French Revolution, to the monetary horror story of Weimar Germany in the 1920s.

His key point is that inflations and hyperinflations don’t just hurt money, they hurt people and the societies they live in. Inflating money is less trustworthy money, and so people doing business trust each other less. Plus, those who are farthest from the source of artificially created money suffer the most (the “Cantillon effect”).

And now the social debasement is clear for all to see. The 99% blame the 1%, the 1% blame the 47%, the private sector blames the public sector, the public sector returns the sentiment … the young blame the old, everyone blame the rich … yet few question the ideas behind government or central banks …

I’d feel a whole lot better if central banks stopped playing games with money….

All I see is more of the same – more money debasement, more unintended consequences and more social disorder. Since I worry that it will be Great Disorder, I remain very bullish on safe havens.

In just 10 days we will see how the US elections turn out. Depending on what happens after, the US will either remain as one of those safe havens (and perhaps become even more of one) or those of us who reside here will need to start thinking more globally. I know a lot of thoughtful people who are already contemplating (if not acting on) plans to make sure their life savings maintain their buying power through the coming decade. I remain optimistic that we will set ourselves on a course that ends in a safe harbor, although the sailing will be quite volatile. What Dylan describes are the unintended consequences of people who think they understand macroeconomics and who are well-intentioned but whose policies can be most disruptive.

Popular Delusions

Memo to Central Banks: You’re debasing more than our currency

by Dylan Grice, Societe Generale

At its most fundamental level, economic activity is no more than an exchange between strangers. It depends, therefore, on a degree of trust between strangers. Since money is the agent of exchange, it is the agent of trust. Debasing money therefore debases trust. History is replete with Great Disorders in which social cohesion has been undermined by currency debasements. The multi-decade credit inflation can now be seen to have had similarly corrosive effects. Yet central banks continue down the same route. The writing is on the wall. Further debasement of money will cause further debasement of society. I fear a Great Disorder.

I am more worried than I have ever been about the clouds gathering today (which may be the most wonderful contrary indicator you could hope for…). I hope they pass without breaking, but I fear the defining feature of coming decades will be a Great Disorder of the sort which has defined past epochs and scarred whole generations.

“Next to language, money is the most important medium through which modern societies communicate” writes Bernd Widdig in his masterful analysis of Germany’s inflation crisis“Culture and Inflation in Weimar Germany.” His may be an abstract observation, but it has the commendable merit of being true … all economic activity requires the cooperation of strangers and therefore, a degree of trust between cooperating strangers. Since money is the agent of such mutual trust, debasing money implies debasing the trust upon which social cohesion rests.

So I keep wondering to myself, do our money-printing central banks and their cheerleaders understand the full consequences of the monetary debasement they continue to engineer? Inflation of the CPI might be a consequence both seen and measurable. A broad inflation of asset prices might be a consequence seen, though not measurable. But what about the consequences that are unseen but unmeasurable – and are all the more destructive for it? I feel queasy about the enthusiasm with which our wise economists play games with something about which we have such a poor understanding.

If you take a look around you, any artefact you see will only be there thanks to the cooperative behaviour of lots of people you don’t know. You will probably never know them, nor they you. The screen you watch on your terminal, the content you read, the orders which make the prices flicker … the coffee you drink, the cup you hold, the bin you throw it in afterwards … all your clothes, all your accessories, all the buildings you’ve been in, all the cars … you get the idea. Without exception everything you own, everything you want to own, everything you need, and everything you think you need embodies the different skills and talents of a mind-boggling number of complete strangers. In a very real sense we constantly trust in strangers to a degree, as strangers trust us. Such cooperative activity is to everyone’s great benefit and I find it is a marvellous thing to behold.

The value strangers put on each other’s contributions manifests itself in prices, and prices require money. So it is through money that we express the extent of our appreciation for the many different talents embedded in each thing we consume, and through money that our skills are in turn valued by others. Money, in other words, is the agent of this anonymous exchange, and therefore money is also the agent of the hidden trust on which it depends. Thus, as Bernd Widdig reflects in his book (which I urge you all to read), money …

“… is more than simply a tool for economic exchange; its different qualities shape the way modern people think, how they make sense of their reality, how they communicate, and ultimately how they find their place and identity in a modern environment.”

Debasing money might be expected to have effects beyond the merely financial domain. Of course, there are many ways to debase money. Coin can be clipped, paper money can be printed, credit can be created on the basis of demand deposits which aren’t there … the effects are ultimately the same though: the implied trust that money communicates through society is eroded.

To see how, consider the example of money printing by authorities. We know that such an exercise raises revenues since the authorities now have a very real increase in purchasing power. But we also know that revenue cannot be raised by one party without another party paying. So who pays?

If the authorities raise taxes explicitly and openly, voters know exactly why they have less spending power. They also know how much less spending power they have. But if the authorities instead raise money by simply printing it, they raise the revenue by stealth. No one knows upon whom the burden falls. People notice only that they can’t afford the things they used to be able to afford, or they can’t afford the things which everyone else can afford. They know that something is wrong, but they just don’t know what, why, or who is to blame. So inevitably they look for someone to blame.

The dynamic is similar to that found in the well-worn plot line in which a group of strangers are initially brought together in happier circumstances, such as a cruise, a long train journey or a weekend away. In the beginning, spirits are high. The strangers exchange jokes and get to know one another as the journey begins. Then some crime is committed. They know it must be one of them, but they don’t know who. A great suspicion ensues. All trust between them is broken down and the infighting begins….

So it is with monetary debasement, as Keynes understood deeply (so deeply, in fact, that it’s ironic so many of today’s crude Keynesians support QE so enthusiastically). In 1921 he said:

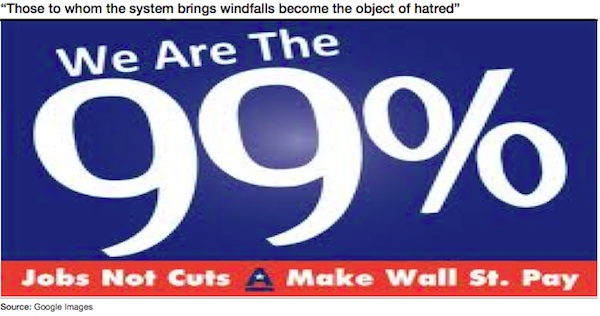

“By a continuing process of inflation, Governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some …. Those to whom the system brings windfalls …. become “profiteers” who are the object of the hatred … the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery .. Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

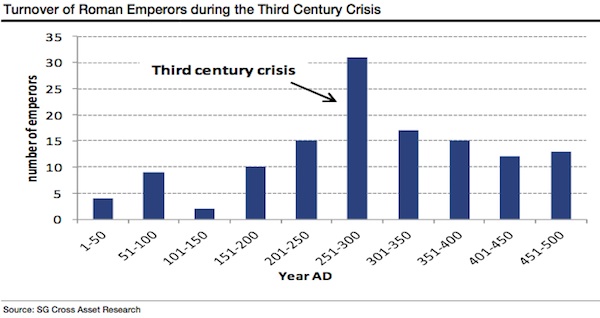

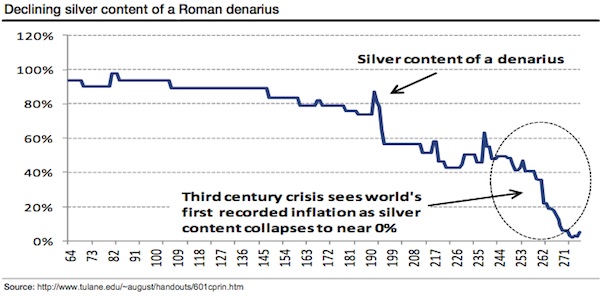

History is replete with Great Disorders in which currency debasement has coincided with social infighting and scapegoating. I have written in the past about the Roman inflation of the Third Century AD. The following chart shows the rapid turnover of emperors during what is known as the Third Century Crisis. As trade declined, crops failed and the military suffered what must have seemed like constant defeat, it wasn’t difficult for a successful or even popular general to convince the rest of the empire that he’d make a better fist of governing.

But this political turnover was accompanied by what may be history’s first recorded instance of systematic currency debasement. With the empire no longer expanding and barbarians being forced westwards by the migrations of the Steppe peoples, Rome’s borders were under threat. But the money required to fund defence wasn’t there. Successive emperors therefore reached the same conclusions that kings, princes, tyrants and democratically elected governments would later reach down the ages when faced with a perceived “shortage of money”: they created more by debasing the existing stock. In the second half of the third century, the silver content of a denarius had shrunk to zero. Copper coins disappeared altogether.

This debasement of currency also coincided with a debasement of society. Factions grew more suspicious of one another. Communities fragmented. And one part of the community bore the brunt of the fears: Christians. While Rome had always welcomed new religions and Gods, incorporating new foreign deities as their empire grew, Christians were altogether different. They rejected Rome’s gods. They refused to pray to them. They said that only their God was deserving of worship. The rest of the Romans concluded that this obstinacy must be a source of great anger for their own ancient Roman gods, and supposed that those gods must now be exacting their own great punishment in return.

So the Romans turned on their Christians with a great violence which lasted throughout the period of the currency debasement but peaked with Diocletian’s edict of 303 AD. The edict decreed, among other things, that Christian meeting places be destroyed, Christians holding office be stripped of that office, Christian freedmen be made slaves once more and all scriptures be destroyed. Diocletian’s earlier edict, of 301 AD, sought to regulate prices and set out punishments for ‘profiteers’ whose prices deviated from those set out in the edict.

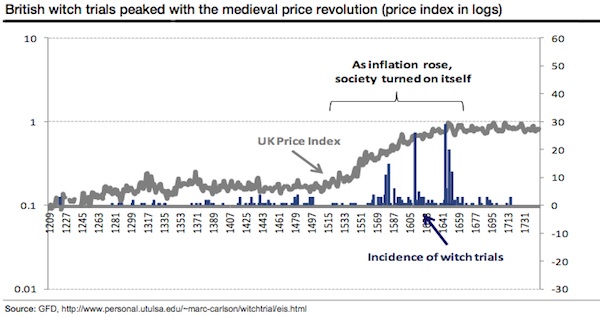

A similar dynamic seems evident during Europe’s medieval inflations, only now, the confused and vain effort to make sense of the enveloping turmoil saw the blame focus on suspected witches. The following chart shows the UK price index over the period with the incidence of witchcraft trials. Note the peak in trials coinciding with the peak of the price revolution.

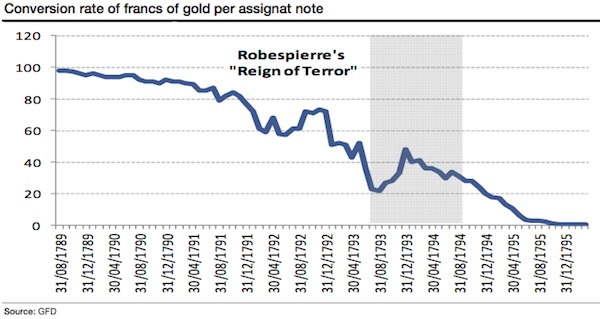

Were the same dynamics at work during the French Revolution of 1789? The narrative of Madame Guillotine and her bloody role is well known. However, the execution of royalty by the Paris Commune didn’t begin until 1792, and the Reign of Terror in which Robespierre’s Orwellian sounding “Committee of Public Safety” slaughtered 17,000 nobles and counter-revolutionaries didn’t start until well into 1793. In the words of guillotined revolutionary Georges Danton, this is when the French revolution “ate itself”. But the coincidence of these events to the monetary debasement is striking.

The political violence was justified in part by blaming nobles and counter-revolutionaries for galloping inflation in food prices. It saw ‘speculators’ banned from trading gold, and prices for firewood, coal and grain became subject to strict controls. According to Andrew Dickson White, author of “Fiat Money Inflation in France”, (echoing Keynes’ remark that“wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery”) “economic calculation gave way to feverish speculation across the country.”

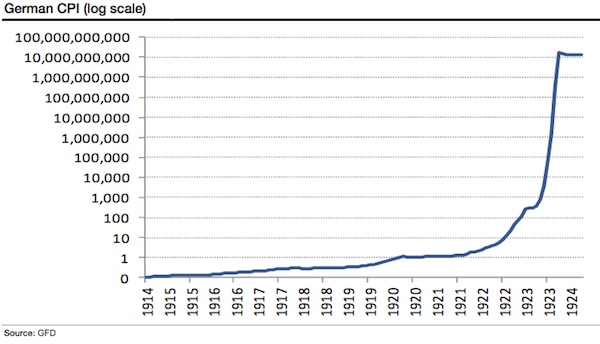

However, the most tragic of all the inflations in my opinion, and certainly the starkest example of a society turning on itself was the German hyperinflation. Its causes are well known. Morally and financially bankrupt by the First World War, the reparation demands of the Allies (which Keynes argued vociferously against) followed by the French occupation of the Ruhr served to humiliate a once-mighty nation, already on its knees.

And it really was on its knees. Germany simply had no way to pay. The revolution following the flight of the Kaiser was incomplete. Concern was widespread that Germany would follow the path blazed by Moscow’s Bolsheviks only a year earlier. A de facto civil war was being fought on the streets of major cities between extremist mobs of the left and right. Six million veterans newly demobilized, demoralized, dazed and without work were unable to support their families … the great political need was to pay off the “internal debts” of pensions, life insurance and welfare support in any way possible. The risk of printing whatever was required was well understood. Bernhard Dernberg, vice chancellor in 1919, found himself overwhelmed with promises to pay for the war disabled, food subsidies, unemployment insurance, etc., but everyone knew where the money was coming from:

“A decision of the National Assembly is made. On its basis, Reich Treasury bills are printed and on the basis of the Reich Treasury bills, notes are printed. That is our money. The result is that we have a pure assignat economy.”

But print they did. Prices would rise by a factor of one trillion. At the end of the war, Germany owed 154bn Reichmarks to its creditors. By November 1923, that sum measured in 1914 purchasing power was worth only 15 pfennigs.

It is difficult to comprehend the psychological trauma inflicted by this episode. Inflation inverted the efficacy of correct behaviour. It turned the ethics of thrift, frugality and notions such as working hard today to bring benefit tomorrow completely on their heads. Why work today when your rewards would mean nothing tomorrow? What use thrift and saving? Why not just borrow in depreciating currency? Those who had worked and saved all their lives, done everything correctly and invested what they had been told was safe, were mercilessly punished for their trust in established principles, and their inability to see the danger coming. Those with no such faith who had seen the danger coming had benefited handsomely.

Everything, in other words, was dependent on one’s ability to speculate, recalling what Dickson White observed of the French Revolution and Keynes reflections more generally. Erich Remarque is best known for his anti-war novel “All Quiet on the Western Front” but perhaps his best work was the “The Black Obelisk” set in the early Weimar period, and a penetrating meditation on the upside-down world of inflation. The protagonist Georg poignantly captures this speculative imperative when he sits down and lets out a long sigh:

“Thank God that it’s Sunday tomorrow … there are no rates of exchange for the dollar. Inflation stops for one day of the week. That was surely not God’s intention when he created Sunday.”

Perhaps the most eloquent chronicler of the Weimar hyperinflation was Elias Canetti, whose mother moved him from the security of Zurich to Frankfurt in 1921 to take advantage of cheaper living. Canetti never forgave her, and his life’s work shows what a lasting impression the move from heaven to hell made:

“A man who has been accustomed to rely on (the monetary value of the mark) cannot help feeling its degradation as his own. He has identified himself with it for too long, and his confidence in it has been like his confidence in himself … Whatever he is or was, like the million he always wanted, he becomes nothing”

More tragic still was what German society became during the inflation. Like other Axis countries on the wrong side of the War and now in the grip of hyperinflation, Germany turned viciously on its Jews. It blamed them for the surrounding evil as Romans had blamed Christians, medieval Europeans had suspected witches, and French revolutionaries had blamed the nobility during previous inflations. In his classic “Crowds and Power”, Canetti attributed the horror of National Socialism directly to a “morbid re-enaction impulse”.

“No one ever forgets a sudden depreciation of himself, for it is too painful … The natural tendency afterwards is to find something which is worth even less than oneself, which one can despise as one was despised oneself. It is not enough to take over an old contempt and to maintain it at the same level. What is wanted is a dynamic process of humiliation Something must be treated in such a way that it becomes worth less and less, as the unit of money did during the inflation. And this process must be continued until its object is reduced to a state of utter worthlessness. … In its treatment of the Jews, National Socialism repeated the process of inflation with great precision. First they were attacked as wicked and dangerous., as enemies; then, there not being enough in Germany itself, those in the conquered territories were gathered in; and finally they were treated literally as vermin, to be destroyed with impunity by the million.

All this is very disturbing stuff, but testament to a relationship between currency devaluation and social devaluation. Mine is not a complete or in any way rigorous analysis, I know. I emphasize that it’s not in any way meant as some sort of crude mapping on to today’s environment. My point is to show that money operates in many social domains beyond the financial, and that tying currency devaluation to social devaluation might have some merit.

Consider some recent and less extreme currency inflations. The 1970s bear market in equities saw relatively mild inflation which was also characterized by relatively mild but nevertheless real factionalization of society. An ideological left vs right battle played out between labour and capital, unions and non-unions and perhaps most bizarrely, betweenrock and disco. As already stated, money implies a trust in the future. It implies that today’s money can be used in the future. So in the era of punk, did the Sex Pistols provide the most concise commentary of the malaise?

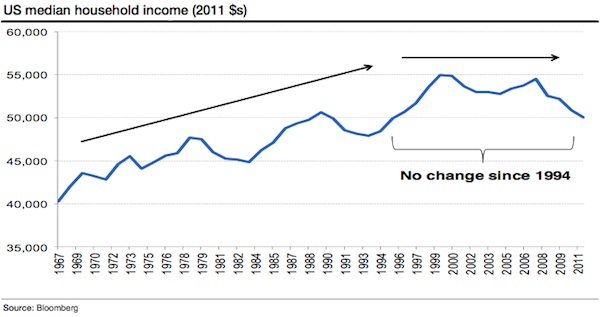

Which brings us to today. Despite the CPI inflation of the 1970s receding, our central banks have continued to play games with money. We’ve since lived through what might be the largest credit inflation in financial history, a credit hyperinflation. Where has it left us? Median US household incomes have been stagnant for the best part of twenty years (chart below)

Yet inequality has surged. While a record number of Americans are on food stamps, the top 1% of income earners are taking a larger share of total income than since the peak of the 1920s credit inflation. Moreover, the growth in that share has coincided almost exactly with the more recent credit inflation.

These phenomena are inflation’s hallmarks. In the Keynes quote above, he alludes to the “artificial and iniquitous redistribution of wealth” inflation imposes on society without being specific. What actually happens is that artificially created money redistributes wealth towards those closest to it, to the detriment of those furthest away.

Richard Cantillon (writing decades before Adam Smith) was the first to observe this effect (hence “Cantillon effect”). He showed how those closest to the money source benefited unfairly at the expense of others, by thinking through the effects in Spain and Portugal of the influx of gold from the new world as follows:

“If the increase of actual money comes from mines of gold or silver … the owner of these mines, the adventurers, the smelters, refiners, and all the other workers will increase their expenditures in proportion to their gains. . . . All this increase of expenditures in meat, wine, wool, etc. diminishes of necessity the share of the other inhabitants of the state who do not participate at first in the wealth of the mines in question. The altercations of the market, or the demand for meat, wine, wool, etc. being more intense than usual, will not fail to raise their prices … Those then who will suffer from this dearness … will be first of all the landowners, during the term of their leases, then their domestic servants and all the workmen or fixed wage-earners … All these must diminish their expenditure in proportion to the new consumption …

(Quoted in Mark Thornton, “Cantillon on the Cause of the Business Cycle”Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics Vol 9, No 3 [Fall 2006])

In other words, the beneficiaries of newly created money spend that money and bid up the price of goods with their higher demand. Those who suffer are those who have to pay newly higher prices but did not benefit from the newly created money.

The credit inflation analog to the Cantillon effect has played out perfectly in recent decades. Central banks provided cheap money to banks, the cheap money artificially inflated asset prices, artificially inflated asset prices made anyone connected to those assets rich as we became a nation of speculators, those riches were achieved at everyone else’s expense, and ‘everyone else’ has now realized what has happened and is understandable enraged … as Keynes explained, “Those to whom the system brings windfalls …. are the object of the hatred.

And now the social debasement is clear for all to see. The 99% blame the 1%, the 1% blame the 47%, the private sector blames the public sector, the public sector returns the sentiment … the young blame the old, everyone blame the rich … yet few question the ideas behind government or central banks …

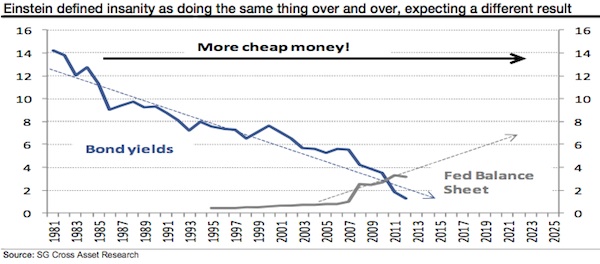

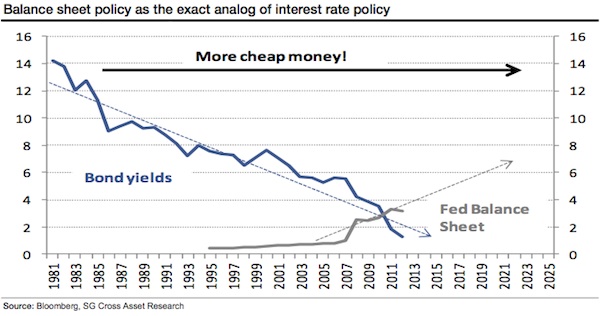

I’d feel a whole lot better if central banks stopped playing games with money. But I can’t see that happening anytime soon. The ECB has thrown the towel in, following the SNB last year in committing effectively to print unlimited amounts of money for the greater good. The BoE and the Fed have long since made a virtue of what was once considered a necessity, with what was once the unconventional conventional. As James Bullard told everyone a few weeks before the last Fed meeting, lest there be any doubt:

“Markets have this idea that, there’s QE1 and QE2, so QE3 must be the same as those previous ones. It’s not that clear to me that this is the way this is going … it would just be to do balance sheet policy as the exact analogue of interest rate policy.”

In other words, the central banks’ balance sheets are the new policy tool. As interest rates embarked on a multi-year decline from the 1980s on, central bank balance sheets are set to embark on a multi-year climb …

So as Nobel Prize winning experts in economics punch the air because inflation expectations have been rising since the policy was announced, “It’s the whole point of the exercise” (Duh!) the BoE admits that QE has mainly benefited the rich, but vows to continue anyway.

All I see is more of the same – more money debasement, more unintended consequences and more social disorder. Since I worry that it will be Great Disorder, I remain very bullish on safe havens. The next few issues of Popular Delusions will outline some thoughts on what exactly that means.

Like Outside the Box? Then we think you’ll love John’s premium product,Over My Shoulder. Each week John Mauldin sends his Over My Shouldersubscribers the most interesting items that he personally cherry picks from the dozens of books, reports, and articles he reads each week as part of his research.

Learn More About Over My Shoulder

Outside the Box is a free weekly economic e-letter by best-selling author and renowned financial expert, John Mauldin. You can learn more and get your free subscription by visiting http://www.mauldineconomics.com.

To subscribe to John Mauldin’s e-letter, please click here:

http://www.mauldineconomics.com/subscribe

To change your email address, please click here:

http://www.mauldineconomics.com/change-address