Currency

Global Currencies Madness:

When central banks and politicians “manage” global currencies, we can expect:

- Exponentially increasing debt and currency devaluations

- Massive inflations and deflationary crashes.

- Transfer of wealth from the many to the few.

- Derivatives exceeding $1,000 Trillion and eventually a crash.

- A mathematically inevitable financial collapse.

- Monetary and fiscal madness.

- Booms and busts.

- Much higher gold and silver prices.

It has happened before and it will happen again…

Last Century Madness:

- Weimar inflation in Germany 1921-1923: The exchange rate for Marks changed from 90 Marks to the US dollar in 1921 to over 4 Trillion Marks to the US dollar in about 2 years.

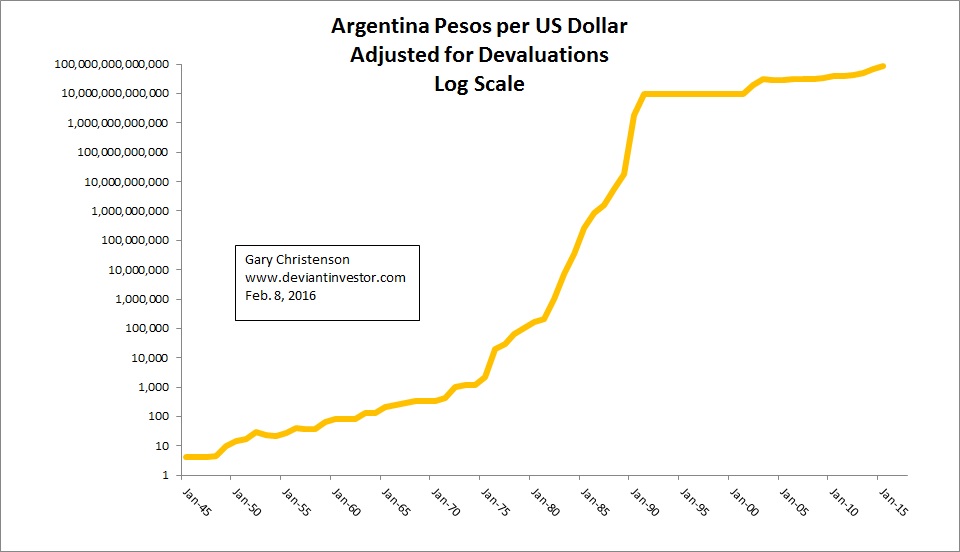

- Argentina devalued their peso and exponentially expanded the currency in circulation so rapidly that Argentina lopped off 13 zeros since 1950.

- Zimbabwe printed so many trillions of Z-dollars that inflation, according to Wikipedia, exceeded 200 million percent in 2008.

Current Monetary Madness:

Japan has created a national debt that exceeds 1,000 Trillion yen, about 250% of their GDP. According to the IMF, Japan’s debt is “unsustainable.”

The US national debt (official only) currently exceeds $19 Trillion, up from $398 Billion in 1971, $5.6 Trillion in 2000, and $10.1 Trillion in October 2008. National debt has increased at a compounded (exponential) annual rate of about 9% per year since 1971.

Does anyone expect the debt will be repaid, reduced, or even stabilized? I think it is clear that the debt will be rolled over and increased until it must be inflated away or defaulted. This is political and central bank supported monetary madness. Exponential increases inevitably end badly.

(The U.S. version of monetary madness.)

(The Argentina version of monetary madness.)

(The Argentina version of monetary madness.)

Central Bank Monetary Madness:

Exponential debt increases appear normal in a central bank controlled financial world that benefits the political and financial elite at the expense of the middle and lower classes. QE, ZIRP, and NIRP (negative interest rates) are recent examples of central bank responses to their self-created problems of debt based fiat currencies, exponential increases in debt, and uncontrolled deficit spending by governments. Fiscal and monetary madness prevails!

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard on the DANGERS of negative interest rates:

“Huw Van Seenis, from Morgan Stanley, calls negative rates (NIRP) a “dangerous experiment” that undermines the mechanism of quantitative easing rather than enforcing it…”

“Narayana Kocherlakota, ex-head of the Minneapolis federal Reserve, reluctantly backs NIRP as deep as -3% but calls it a “gigantic fiscal policy failure” that central banks must resort to such absurdities.”

“Morgan Stanley said that once negative rates fall below 0.2%, the damage to bank earnings goes “exponential” and ultimately endangers the whole system of free banking in Europe that we take for granted.”

My comment: The financial world is descending into an abyss of monetary madness as indicated by:

- Negative interest rates are a “dangerous experiment” and NOT a solution. ($7 Trillion and counting…)

- “gigantic fiscal policy failure” – (They address the consequences of bad policy with worse policy!)

- “damage to bank earnings goes exponential” – (And then what? Bail-ins and bail-outs? More QE and even more negative interest rates? Banking collapse?)

- the debt will never be repaid – (It looks like a safe bet.)

- “helicopter money” – (When all else fails…)

CONCLUSIONS:

- A world of fiat currencies “managed” by central banks descends into the trap of exponentially increasing debt that leads, slowly or rapidly, toward monetary madness and … Train wreck ahead!

- QE has morphed into $7 Trillion of global sovereign debt “paying” negative interest rates. Think “gigantic fiscal policy failure.” At almost any other time in history negative interest rates would have been viewed as insane policy. Monetary madness or … desperate to do something?

- Gold and silver are better solutions and are antidotes to central bank devaluations. One might object to gold for many reasons but those reasons seem minor or irrelevant in the face of exponentially increasing (unpayable) debt, negative interest rates, and ongoing monetary madness.

We have been warned!

Gary Christenson

The Deviant Investor

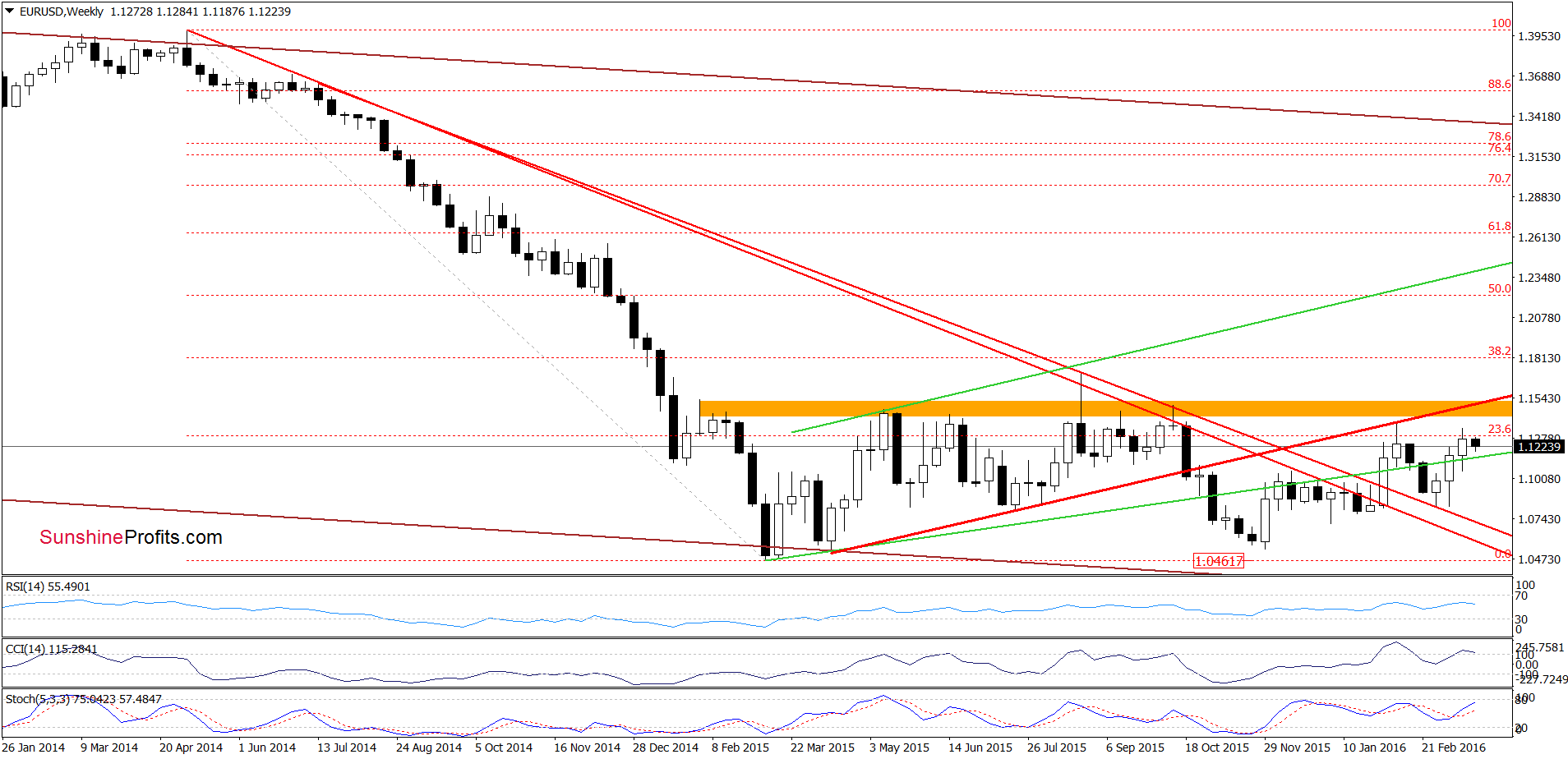

Forex Trading Alert sent to subscribers on March 22, 2016, 10:57 AM.

In our opinion the following forex trading positions are justified – summary:

- EUR/USD: short (stop-loss order at 1.1512; initial downside target at 1.0572)

- GBP/USD: none

- USD/JPY: none

- USD/CAD: none

- USD/CHF: none

- AUD/USD: none

Earlier today, official data showed that the U.K. rate of consumer price inflation increased by 0.3% in Feb, missing analysts’ forecasts. Additionally, although month-over-month consumer prices rose by 0.2% in the previous month, the data disappointed market participants, which pushed GBP/USD under 1.4300. How low could the pair go in the coming days?

Summary

Summary

– The Fed was much more dovish than the markets had expected, resulting in broad USD weakness.

– A weaker USD will help the US to more quickly close its output gap.

– Current USD weakness will reverse one of two ways.

– Either other central banks will ease in response to local FX strength, or strong US data will confirm the need for tighter US monetary policy.

– The commodity rally could very well run out of steam soon, given substantial producer hedging appetite and the possibility of a USD turnaround.

Mario Draghi pledged to destroy the Euro last week with ECB Bazooka money. Meanwhile, Japan continues to debase the Yen at a record  pace, and Venezuela is in the process of achieving outright hyperinflationary status. Simultaneously, currencies around the world are in an unprecedented suicidal race to parity — OR ZERO – whichever comes first. All while the blasphemous Banksters in the City of London lick their chops on Threadneedle Street, knowing full well that their devious plans to kill cash entirely are well underway.

pace, and Venezuela is in the process of achieving outright hyperinflationary status. Simultaneously, currencies around the world are in an unprecedented suicidal race to parity — OR ZERO – whichever comes first. All while the blasphemous Banksters in the City of London lick their chops on Threadneedle Street, knowing full well that their devious plans to kill cash entirely are well underway.

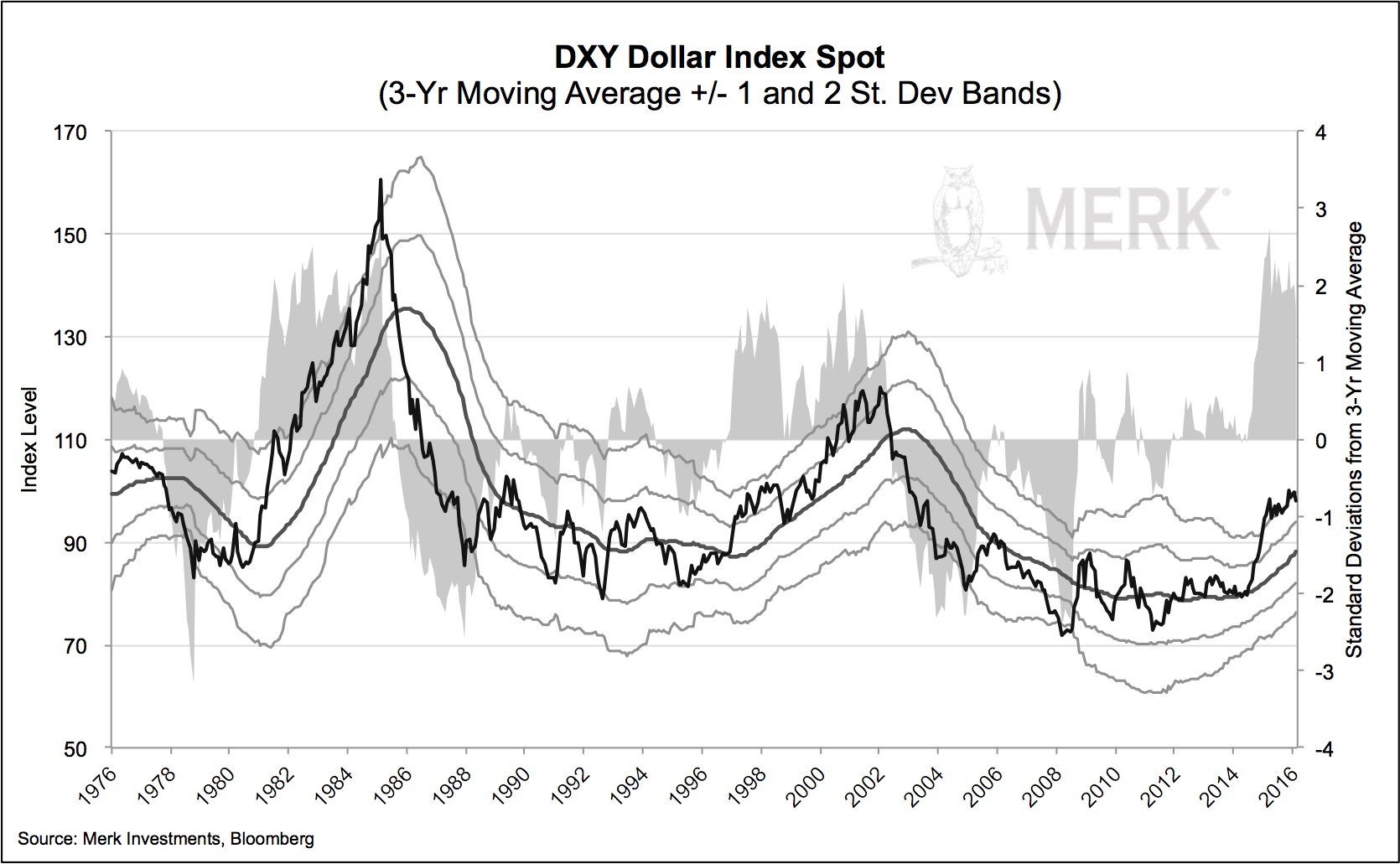

Is the dollar’s seemingly relentless rise in recent years coming to an end? What are the implications not only for the greenback, but other currencies and markets around the world?

The chart below shows the U.S. dollar index over the past 40 years together with its longer term moving average, as well as 1 and 2 standard deviation bands. To some the chart may suggest that exchange rates are mean reverting; some will see a longer-term declining trend in the dollar; others will point to what may be considered an extreme valuation given that the dollar index has been around 2 standard deviations above its moving average. To us, the fact that the dollar has moved so far from its moving average, gives rise to the question whether the dollar rally may be over. Let’s consider some arguments for and against ‘peak dollar’:

U.S. rate hikes?

It’s widely anticipated that the Fed will continue to raise interest rates. So why would the dollar not rise? It turns out that we have been told for years now that the Fed will ‘exit’ from its extraordinarily accommodative policy. In our analysis, the U.S. dollar historically appreciates in anticipation of a hiking cycle, but not necessarily as rates actually move higher.

Rate differentials

What about rate differentials? The European Central Bank (ECB) just lowered rates again. While all else equal, a high interest rate differential may benefit the higher yielding currency, all else is rarely equal. Betting on such rate differentials is also referred to as a ‘carry trade’ strategy. In our analysis, carry trade strategies tend to perform well in ‘risk on’ environments, i.e. in environments when equities and other ‘risk assets’ do well. Let’s pause to reflect that the U.S. dollar historically is considered a ‘safe haven’ when there is a ‘flight to quality.’ Remember 2008, when the dollar was widely considered the ‘only safe place in town’? Well, the yen substantially outperformed the greenback that year, but, yes, the dollar – and notably U.S. Treasuries – were two of the few places where investors found refuge.

But we have observed that for some time now, the U.S. dollar has tended to follow dynamics more typically associated with a high yielding currency, that is to rally in conjunction with the equity markets. This is no accident, as, on a relative basis, the U.S. dollar, has indeed become a high yielding currency versus many of its peers. The flip side of that is that we have observed the dollar often declines when equity markets plunge. This suggests that investors might want to gain some non-dollar exposure as a way to diversify their portfolio. Except they might want to hold non-dollar cash rather than equities, as international equities may also suffer when U.S. equities are under pressure.

Rates bottoming in rest of the world?

We have heard many central bankers complain that their currencies are overvalued and that rates might go lower. But last week, ECB chief Mario Draghi released what we think was a bombshell. During the Q&A of last week’s press conference, he said: “From today’s perspective, and taking into account the support of our measures to growth and inflation, we don’t anticipate that it will be necessary to reduce rates further.” (bolding added) No, he did not misspeak, as he mentioned a second time during the press conference that rates may not go down any further. There are a variety of reasons why he might indicate that rates have bottomed, including:

- Negative interest rates have been difficult to work with for some banks. Notably, Draghi pointed out that banks lose money on some loans linked to overnight lending rates that are negative. By signaling that rates may not go down any further, banks may not restrict lending based on a fear that they may face more losses as rates go deeper into negative territory.

- Draghi appears to have shifted towards a new regime in trying to jumpstart growth in the Eurozone, focusing on boosting bank profitability with another newly announced program (TLTRO II) that, in our analysis, could cut bank funding cost in half for all Eurozone banks. As such, he appears to acknowledge that weakening the euro has not been the panacea to fix the ills of the Eurozone.

- Data in the Eurozone haven’t been so bad. Indeed, listening to Draghi over the past 9 months, a lot of what he looks at looks pretty decent. In fact, just about all negatives he cited at his most recent press conference were risks outside of the Eurozone (global growth) or at least partially outside the control of the ECB (low energy prices).

The conclusion we draw from this is that the bottom of the interest rate cycle may well be in for the Eurozone. Take Draghi’s word for it, not ours. And we think his position creates a whole different dynamic for the U.S. dollar.

On a somewhat related note, we have been arguing for some time that interest rates in Sweden, for example, are way too low. The economy there has good growth and low unemployment; it’s just that inflation is rather low. In our view, the Swedish central bank (Risksbank) has been paranoid about ever more negative rates in the Eurozone; with that risk off the table, the Riksbank may soon be courageous enough to reverse course.

Swiss National Bank President Jordan has also come out [saying?] that there’s a limit as to how far rates can go down.

Commodity currencies

If you see a trend above, these are all European currencies. In contrast, so-called commodity currencies (e.g. the Australian dollar and Canadian dollar) have not been at zero or in negative territory. The dynamics there have also not followed traditional patterns. Still, Mr. Poloz, the head of the Bank of Canada (BoC), last week stated that the BoC wants to see how fiscal policy plays out before deciding on whether to cut rates further. Canada is one of the few countries that appears to be getting a serious fiscal stimulus (Prime Minister Trudeau was quick to discard his election promise to only have minor deficits).

Australia is a bit of a special base, as central bank governor’s Glenn Stevens term is expiring later this year; if we understand Mr. Stevens correctly, he wants out as the governor that did not need to resort to extraordinary policies. Indeed, the Australian economy has rapidly been adjusting, with the weaker Australian dollar helping.

New Zealand, also considered a commodity country, in contrast, just lowered rates again, a reflection that the economy might have a more difficult time adjusting than Australia’s.

Emerging markets

All that said, before we get too far ahead of ourselves, let’s have a look at emerging market currencies. After declining rather substantially, they may be due for a rebound. But let’s not forget that these tend to be tightly managed currencies. The dynamics there, in our analysis, are much more driven by liquidity than many other factors. And may make these currencies move more in tandem with U.S. equities.

Stock market?!

At the risk of oversimplification, the dollar’s fate over the coming months may well be decided by how the stock market is doing. In many ways, the Fed’s actions may also be tied to how the stock market is doing (but that’s an analysis for another day). If our analysis is correct, a rising equity market may bode well for the U.S. dollar; a falling equity market may bode poorly for the greenback.

We may be a tad biased, having provided an analysis last August that we think a bear market is upon us. In the context here, we might want to add that sovereign wealth funds may need to sell U.S. dollar denominated investments to cover budget shortfalls back home, providing pressure on both equities and the greenback.

Axel Merk

Merk Investments, Manager of the Merk Funds