TMR: With so many commodities in the mild, cool, cold and freezing zones currently and in the future, does that mean we could see mines being shut down?

LM: A steep drop in the commodity price certainly could indicate that we have a period coming where strong oversupply means that producers may need to shut down, especially the higher cost ones. If a commodity has been very expensive in the past, meaning its price has been much higher than its cost of production, a steep drop in price doesn’t necessarily mean output would be curtailed. It just means that the market is returning to some sense of normalcy. Copper is a good example of that.

Gold is a case where prices have come down quite a bit too, but because of lack of investor interest rather than needing to shut down gold mines. Aluminum is a case where the market is much oversupplied and the commodity is under some cost pressure. We’ve seen prices come off quite a bit in aluminum, but our heat chart doesn’t show prices are going to decrease much further, simply because prices can’t fall much more. They’ve gotten to the point where producers have to start shutting down because of overcapacity.

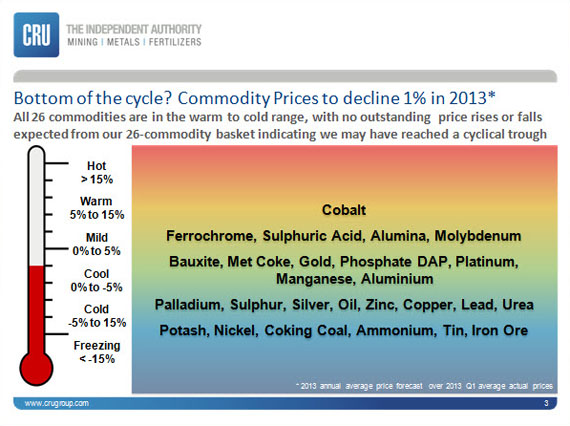

TMR: Has the lack of heat in your forecast led you to conclude that the market for these metals has hit a cyclical trough?

LM: That is our view on 2013, but by 2017, we’re looking at markets that are sending a signal to producers to cut back or maybe not ramp up capacity quite so quickly.

The macroeconomic environment is uncertain. Is China going to pick up? Is the U.S. going to pick up? Is Europe ever going to come out of recession? With so many questions on the demand side, producers are being very, very cautious.

We’re probably in the cyclical trough now and I would point to October 2012 as an inflection point. At least in exchange-traded commodities, investors were selling off because they realized that Chinese economic growth was not going to be 9% anymore. It was going to be something more like 7% or 7.5%. There also was a recognition that the U.S. wasn’t going to be picking up and that Europe wasn’t going to do very well in the coming year. Then, of course, we had another selloff in the spring, in March–April, because, again, the economic growth prospects weren’t very good. We’re probably in the low period right now. It’s hard to say how long cyclical troughs last because they vary by commodity.

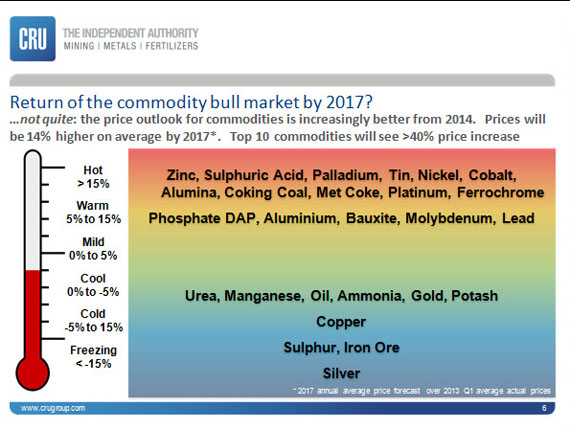

Depending on the commodity it takes a longer time or a shorter time to shut a mine or shut an operation. A lot of commodities are sold on contract basis, on a one-year contract or six-month, nine-month, etc. Production happens and continues to happen because an agreed-upon arrangement exists. It takes more than six months for commodities to really respond to lower prices. As for the 2017 outlook, today’s lower prices are causing producers to ramp up much more slowly or even cancel new projects. But by the time we get through 2014 and into 2015, we may be back in the situation where we really need more capacity in these commodities.

TMR: What’s CRU’s outlook on China?

TMR: What’s CRU’s outlook on China?

LM: It’s easy to feel depressed about China because we’ve been accustomed to such a fast growing economy, with double-digit industrial production growth. You can’t sustain that kind of growth for long. The economy now is going through a transition. If you think about Korea in 2000 versus where it was in 1980, it’s a similar situation, but China is a much, much bigger economy. Our view is that China will still achieve strong GDP growth in the 7–8% range over the next couple of years. Industrial production growth won’t probably be double-digits except in a very good month or a quarter here and there, but something in the 7–9% range. China still has a lot of infrastructure to build. People will get wealthier and will need and want more and better food. They are going to need more oil and more cars; they are going to want homes and washing machines. Even though the super fast growing commodity story in China may be over, it isn’t as if we’re getting to a point where China is not going to need commodities anymore.

TMR: Does your view of China lead you to conclude that the commodity supercyle is over?

LM: The commodity supercycle is probably over, but I don’t think it’s the death of commodities. The supercycle was after all driven by the unexpected strong growth in China and expected weakness of the U.S. dollar. At the same time, the metals and mining industries had gone through a period cost cutting, so there had been no investment in capacity or exploration. As a result, the mining industry was completely unprepared for the large surge in demand from China starting in 1995 and picking up again after the Asian financial crisis, in 1997, 1998, 1999 and the end of 2000, which was a peak period for commodities in general. That was very attractive for investors and that is what promoted the supercycle. Now we are going to see that back off. China’s commodity growth isn’t going to be 10% year-on-year; it’s going to be much smaller. But don’t forget that economies with large populations in Asia and in Africa are eventually going to be transitioning as well.

TMR: Do precious metals prices tend to be a leading indicator of a cyclical trough or are they more likely to be some of the last commodities to fall?

LM: Precious metals often function as a safe haven in times of high uncertainty. After the financial crash we didn’t know if the economy was going to survive or how we were going to get economic growth. We saw investors very interested in gold and silver at those times. Of course, prices remain very elevated compared to prior to the crash. Precious metals prices certainly seem to be countercyclical and have high demand, both financial and physical, during periods of high uncertainty.

We have witnessed a certain amount of selling in gold and silver since the middle of last year. That’s because the worst-case scenarios, such as a Eurozone breakup or China sliding into recession, didn’t come about. Even President Obama and Congress managed to get past the fiscal cliff. Investors began telling themselves that because the worst didn’t happen, they didn’t need to be invested in safe havens anymore. That caused a selloff in gold and silver that turned out to be a precursor to selloffs in the rest of the metals space. In that respect they were a lead indicator that the worst of the uncertainty had passed. I don’t think you could look at precious metals demand as necessarily a lead indicator for an economic cycle per se. I think they definitely have a role to play during a cycle and may play a leading role again with consumers when things are looking better.

We have witnessed a certain amount of selling in gold and silver since the middle of last year. That’s because the worst-case scenarios, such as a Eurozone breakup or China sliding into recession, didn’t come about. Even President Obama and Congress managed to get past the fiscal cliff. Investors began telling themselves that because the worst didn’t happen, they didn’t need to be invested in safe havens anymore. That caused a selloff in gold and silver that turned out to be a precursor to selloffs in the rest of the metals space. In that respect they were a lead indicator that the worst of the uncertainty had passed. I don’t think you could look at precious metals demand as necessarily a lead indicator for an economic cycle per se. I think they definitely have a role to play during a cycle and may play a leading role again with consumers when things are looking better.

The U.S. economy is on a much stronger footing than it has been since 2006. The U.S. economy has been a nonentity in the story for the last seven years. Our view is that this year we’re likely to get 2.5–3% GDP growth, moving to the 3–3.5% range for the next two years. That is even slightly above trend compared to what demographics would give you. The U.S. economy is really looking in much, much better shape than it has been for quite some time.

Don’t forget that Japan is going to emerge as well. It’s also been an absent actor on the global economic stage. It’s a big economy and it’s going to emerge from this sleepwalking stage in the next year or so. I think that’s very exciting. It’s hard for me to be very negative about what I see over the next two years. Maybe the next six months aren’t that great for commodities, but over the medium to longer term the outlook is very positive.

TMR: What is your outlook for gold, silver, platinum and palladium?

LM: Our forecast is that the gold price peaked in 2012 and that the good times for gold are pretty much over. We expect prices to come down through 2017. In silver that is also the case. If the interest in gold has peaked, the interest in silver is gone and that price is going to come down a lot faster. I certainly would not want to be holding either one of those for any length of time.

Platinum and palladium are a bit different because they are much more industrial type metals. They are produced in very small quantities in markets with supply constraints. Particularly in palladium, we also have had inventories that were coming out of the former Soviet Union and those Russian stockpiles and shipments are ending. There’s no more left there, so we are coming back to the actual private market.

This means producers of palladium now have to increase capacity to meet demand. We’re looking for pretty strong price increases—extremely strong in palladium. That’s one of the super hot commodities. Going out through 2017, platinum would also fall into that super hot period because it’s expected to increase well over 15% over the next five years. We’ve got lower prices now, but new capacity is going to be needed, so prices will pick-up after 2015.

TMR: What other commodities do you expect will move from neutral into the hot category over the next few years?

LM: We’re looking at cobalt, which has had the strongest price increase this year. The best of the price increases are going to be in the very near term and things will slide off after about 2015–2016. Tin also has had some supply constraint problems, so that’s going to move into the hot category next year.

Zinc, which is much oversupplied at the moment, is quite likely to move into the hottest commodity category five years from now because the new mines that we are going to need can’t be financed at today’s prices. With financing as tight as it is, those zinc mines are not going to be started for the next couple of years. It takes quite a few years to bring a zinc mine into production, so we could be looking at a late decade squeeze in zinc.

TMR: What about copper?

LM: Copper prices have been well over $7,000/tonne and have found it quite difficult to break below $6,800/tonne. Copper is likely to be better supplied than it has been for 10 years, so a major shortage going forward is unlikely. Of course, that assumes that the mine supply comes on the way it is supposed to. The mines are coming on in places that traditionally have had some difficulties such as Peru and Africa.

We will probably still see relatively high copper prices, meaning something in the $6,500–7,500/tonne range, to bring on these new mines needed in the next five to seven years to meet demand. Everything in copper hinges on whether or not mine supply comes on as expected.

TMR: Nickel prices have been very weak over the past four or five years; why are you predicting a 41% increase between now and 2017?

LM: Nickel has been punished because it’s in oversupply. Supply came on at the wrong time, just when demand was coming off. Demand hasn’t really picked up terribly well. In China nickel pig iron is used as a cheaper alternative to pure nickel. This was how China dealt with its shortage of nickel resources and its need for more nickel for stainless steel. Stainless steel is a higher-end commodity. China is shifting from heavy industrial or heavy infrastructure to something that’s more consumer oriented and more high-value added. Although the demand for steel and iron ore may go down and those prices may fall, that shift to something consumer oriented is going to support nickel prices going forward. It’s really a China story in nickel again.

TMR: How are gold and silver likely to react to the unwinding of quantitative easing in the U.S., Japan and Europe?

LM: If we get a lot of inflation because of the unwinding of quantitative easing, we may not see the drop off in prices that we’ve forecasted. Our view is that quantitative easing in the U.S. isn’t going to start to get unwound probably until the end of next year to any significant extent. It will be done in a relatively gradual way. Unwinding in Japan probably won’t happen until well after that because its central bank has institutionalized yet another round of it. It’s going to be a gradual process. The winding down will be difficult to time because we can’t even get that information out of the Federal Reserve Board at the moment.

As those uncertainties are reduced and things become clearer, then what we do at CRU is look at sentiment in the next year or two and try to figure out how that affects the price forecast. Then, as we move away from year two, we really should revert to the fundamentals of supply and demand in those markets.

We can’t really see how the current price of silver is justified given that the lack of massive investor influx to support the price. That’s why we expect the price to come down. Gold is a little a bit different, but similar. We look at supply and demand. We look at what investors are doing. Investors have really sold off. The question that you need to ask with gold is what’s going to make investors buy again? Or will they keep unwinding at opportunistic times?

TMR: Do you have an answer to your own question?

LM: The only thing I think that would cause people to buy more gold again and to go through another cycle of this massive investor buying would be if it became a commonly held perception that quantitative easing was going to be unwound in a way that was going to cause very high levels of inflation. In that case, all commodity prices would go up, but certainly with gold and silver as safe havens, the demand for them would be even stronger.

TMR: Where should investors be long with mined commodities?

LM: The best prospects for being long over the next year in exchange-traded type commodities are probably tin and palladium. Looking at 2017, economic growth picks up after 2015. We hope that market conditions are more normalized. We should be getting finished with quantitative easing. We should have better market signals. In those cases probably the really good prospects there for exchange-traded commodities are zinc and nickel.

TMR: Thanks, Lisa, for your insights.

Lisa Morrison was a speaker at the Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration “Current Trends in Mining Finance—An Executive’s Guide” conference.

Lisa Morrison is an industry analyst in the copper and aluminum markets with the CRU Group, a business intelligence company. She specializes in assessing risks to the short-term outlook and is currently building a research platform to help CRU better predict and model investor behavior in the metals market. She has worked at CRU since 1995 and spent 12 years in the firm’s management consulting division working on projects in aluminum, steel and base metals. Prior to CRU, she spent five years at Haver Analytics and before that more than one year at the Korea Trade Promotion Center. Morrison holds a masters degree in economics from New York University and a bachelors in economics from Drew University.

Want to read more Metals Report interviews like this? Sign up for our free e-newsletter, and you’ll learn when new articles have been published. To see a list of recent interviews with industry analysts and commentators, visit our Streetwise Interviews page.

DISCLOSURE:

1) Brian Sylvester conducted this interview for The Metals Report and provides services to The Metals Report as an independent contractor.

2) Streetwise Reports does not accept stock in exchange for services.

3) Lisa Morrison: I was not paid by Streetwise Reports for participating in this interview. Comments and opinions expressed are my own comments and opinions. I had the opportunity to review the interview for accuracy as of the date of the interview and am responsible for the content of the interview.

4) Interviews are edited for clarity. Streetwise Reports does not make editorial comments or change experts statements without their consent.

5) The interview does not constitute investment advice. Each reader is encouraged to consult with his or her individual financial professional and any action a reader takes as a result of information presented here is his or her own responsibility. By opening this page, each reader accepts and agrees to Streetwise Reports’ terms of use and full legal disclaimer.

6) From time to time, Streetwise Reports LLC and its directors, officers, employees or members of their families, as well as persons interviewed for articles and interviews on the site, may have a long or short position in securities mentioned and may make purchases and/or sales of those securities in the open market or otherwise.

What’s Inside:

What’s Inside:

I can still remember being amazed to see fires in the fields along the road. No one seemed to care. It was only decades later, as a young man on Wall Street looking around for some investment opportunities, that I learned the reason for those fires along the Oklahoma roads of my childhood.

I can still remember being amazed to see fires in the fields along the road. No one seemed to care. It was only decades later, as a young man on Wall Street looking around for some investment opportunities, that I learned the reason for those fires along the Oklahoma roads of my childhood. Drought is a normal recurring feature of the climate in most parts of the world. It doesn’t get the attention of a tornado, hurricane or flood. Instead, it’s a slower and less obvious, a much quieter disaster creeping up on us unawares.

Drought is a normal recurring feature of the climate in most parts of the world. It doesn’t get the attention of a tornado, hurricane or flood. Instead, it’s a slower and less obvious, a much quieter disaster creeping up on us unawares.