Gold & Precious Metals

By Bill Bonner

Memories take time. Like history. Or wine. Or cement.

At first, they are loose, fluid…and watery. Then, over time, they dry up…and develop more body…more shape…more substance.

Our recollections from our trip to Argentina are still congealing…setting up like a stone wall. We’ll show it to you in the days ahead.

But today, let’s turn from the pampas to the developed world…to the world of money. That is, let us turn our attention from the vivid world of real things and real people…to the absurd blah blah world of economics.

What happened in the 2 months we were gone? Anything important? Not that we can tell from the papers. The headlines are almost the same as they were when we left.

The Great Correction, for example, hasn’t gone away. Instead, it seems to be intensifying.

In America, 11 million homeowners are still ‘underwater.’ Every one of these houses is a candidate for foreclosure…and every one puts downward pressure on the housing market, which has been falling for the last 5 years with hardly a let-up.

Yes, Dear Reader, this month marks the 5th anniversary of the Great Correction. It began in April ’07, when its weakest link — subprime mortgage debt — snapped. Since then housing has been losing value. And with 11 million houses still priced below the amount of their mortgages, this housing bear market could last for another 5 years before it finally comes to an end.

When housing goes down so do the balance sheets of America’s households. And without improving balance sheets it is very unlikely that households will substantially increase spending. This will leave the economy hobbling along about as it is now…with the lowest growth rate of any post-war ‘recovery’…and completely dependent on more loose change from the feds.

No, that hasn’t changed either. When we left the feds were still trying to sort out a debt crisis by adding more debt. Nothing has changed since. America’s feds keep lending money they don’t have to borrowers who can’t pay it back.

This time, students are the subprime borrowers. Can you imagine a more subprime group? Students don’t have jobs. They’ve never proven they can earn money. Their credit histories are as thin as their resumes. And yet the feds have extended $1 trillion to this group. How long will be before that blows up? Probably not too long.

Meanwhile, in Europe, subprime debt is concentrated at the government level. The subprime borrowers were the countries at the periphery of Europe — Ireland, Portugal, Greece and Spain — who would have a very hard time paying their bills when the lending stopped. When we left, Greece was struggling. Now, it’s Spain.

Read more HERE

By Azizonomics

There is a widely-held notion on the political left that the key economic problem that our civilisation faces is income inequality.

To wit:

America emerged from the Great Depression and the Second World War with a much more equal distribution of income than it had in the 1920s; our society became middle-class in a way it hadn’t been before. This new, more equal society persisted for 30 years. But then we began pulling apart, with huge income gains for those with already high incomes. As the Congressional Budget Office has documented, the 1 percent — the group implicitly singled out in the slogan “We are the 99 percent” — saw its real income nearly quadruple between 1979 and 2007, dwarfing the very modest gains of ordinary Americans. Other evidence shows that within the 1 percent, the richest 0.1 percent and the richest 0.01 percent saw even larger gains.

By 2007, America was about as unequal as it had been on the eve of the Great Depression — and sure enough, just after hitting this milestone, we plunged into the worst slump since the Depression. This probably wasn’t a coincidence, although economists are still working on trying to understand the linkages between inequality and vulnerability to economic crisis.

I mostly agree that income inequality is a huge problem, although I believe that it is a symptom of a wider malaise. But income inequality is an important symptom of that wider malaise.

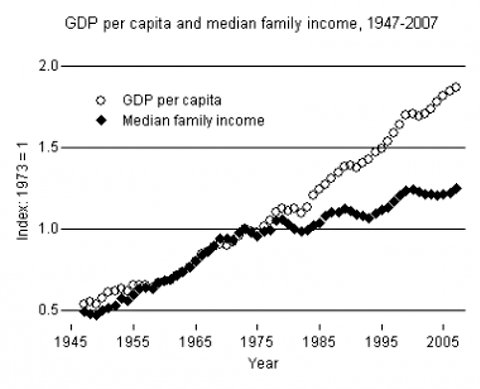

Here’s the key chart:

However it is just as important, perhaps more important to identify the causes of the income inequality.

I have my own pet theory:

The growth in income inequality seems to be largely an outgrowth of giving banks a monopoly over credit creation. In 1971, Richard Nixon severed the link between the dollar and gold, expanding the monopoly on credit creation to a carte blanche to print huge new quantities of dollars and give them to their friends.

Unsurprisingly, this led to a huge growth in the American and global money supplies. This new money was not exactly distributed evenly. A shrinking share has gone to wage labour.

To Read More CLICK HERE

By Alex Daley, Chief Technology Investment Strategist

“What made Instagram worth $1 billion to Facebook?”

When asked this question recently, I responded with an immediate, “Nothing.”

I’m not usually so terse or emphatic with my answers, as any longtime reader knows. But in this case, there really was nothing inherently valuable inside Instagram that made them worth the unbelievable sum Facebook agreed to pay. Yet they did it anyway. Clearly, there’s something missing from a traditional valuation analysis here.

That missing piece is what Instagram could have become in the hands of a competitor or even on its own, had Facebook not gone ahead with the marriage. Nearing its IPO, Facebook was willing to overpay in order to quash any potential risks that Instagram posed, both to the company’s reputation and its content stream.

Instagram by the Numbers

On the surface, Instagram might look like small potatoes. It has only one product: an application for smartphones that can take square, Polaroid-style throwback images, run them through a few cool filters to make them look snazzy, and share them with other users. Even though it has some sharing capability built into its own app, the overwhelming majority of photos are instead posted to Facebook (or Twitter or Posterous or other social network) with the app’s simple integration.

There is no magical computer science involved. The app – minus some intricacies that allowed it to scale to millions of users without buckling under its own weight – is simple enough that most any solid mobile developer could have thrown it together. This is not to dismiss the hard work the twelve-person company put into it – I am sure many late nights were spent on the finer details, squashing bugs, and the like – but it’s not exactly a fighter-jet simulator or climatology model. Facebook obviously didn’t want the company for its cutting-edge patents, code, or other intellectual property.

So maybe it had to do with the user base? True, the application is insanely popular, having been downloaded more than 30 million times according to the App Store statistics from Apple, and another 5 million on Android. (Of course, Apple and Google have it in their best interests to overcount those users, by including updates, reinstalls, upgraded phones, etc. But it is the best proxy we have, and we can reasonably assume Instagram still had tens of millions of users.) Plus, it was named “application of the year” by Apple for 2011, which was bound to further boost its appeal and draw in new users.

But Facebook already counts 850 million registered users, according to its most recent press releases. Even adding 30 million to that number would cause barely a ripple. And given that the most popular use of the application is to upload to your existing Facebook account, we doubt that it will bring many, if any, new users to Facebook. This was not about adding instant market share.

Nor did the two-year-old Instagram bring much in the way of revenue to the table. In fact, the company has no revenue stream at all; it was living off of $7 million in venture capital funds it managed to raise on the back of its early success, having garnered 1.75 million downloads just four months after its launch. (The product, by the way, was built on just $500,000 in seed funding pre-launch.)

No revenue, little money in the bank… you might think a company like that would come cheap. That instead, Facebook believed it justified a $1-billion pricetag tells us that Facebook values the company for something more than Instagram’s application, audience, or earnings.

To Read More CLICK HERE