Currency

Quotable

“Those who have knowledge, don’t predict. Those who predict, don’t have knowledge. ” Lao Tzu, 6th Century BC

Commentary & Analysis

Forecasting, Causality, the Black Swan, and your Edge

I shared this seemingly simple equation with you recently; and today I would like to add a few comments and delve deeper:

The currency equation of expected total return:

![]()

This equation says the primary rationale for holding a particular currency is to maximize total return, and expected total return is a function of the real yield achieved (nominal interest rates minus the inflation rate) and the future exchange rate (that which we are trying to forecast).

Do rising real yields cause the exchange rate to rise … or is it a rising exchange rate, impacting the fundamentals, which leads to rising yields?

In the real-world prices are driven by tangled web of rationales which manifest into a complex array of feedback loops. I think this explains why it is so painfully difficult to determine which variables lead and which follow in a supposed correlation. The world “supposed” is used because correlation is not causality; and worst still, causality itself is suspect as Sir Karl Popper explains (below).

I could give you plenty of examples of when a currency’s relative yield dropped, yet the currency soared, and vice versa. It is rarely an A+B=C causation (though I plead guilty at times pretending it may be that simple). In fact, if you were to stop and calculate the odds of forecasting correctly based on your inherent A+B=C causality mindset, you might start to question the efficacy of ever forecasting again.

In chess, there are 400 different possible positions after the opening two moves. There are 72,084 move combinations after each player has made two moves and over 288 billion scenarios after four moves each. The Shannon Number, which represents a conservative lower bound of the game-tree complexity of chess (the total possible move variations), is thought to be between 10^111 and 10^123. By comparison, there are 10^81 atoms that make up the known universe. I think we can all agree that national and global markets and economies are far more complex thanchess. So tell me again why you think you can predict what will happen next in the markets or in the economy….

Bob Seawright, The Prediction Game

Maybe we should stop looking for causality as a source of confidence for our forecasts; especially if our causality flows from deductive reasoning.

Why we cling to Beliefs

Karl Popper, a German philosopher, referred to the black swan in his 1953 essay on The Problem with Induction. Induction application in the financial world is best known as “back testing.” Reading Popper gives one a deeper understanding of why we cling to beliefs so tightly and assume we can confidently project our expectations into the future and be confident we will be right.

Popper was fond of the philosopher David Hume and used his reasoning for much of the basis of his argument about induction, carrying it further. Popper wrote [my emphasis]:

But Hume held, at the same time, that although induction was rationally invalid, it was a psychological fact, and that we all rely on it. [We do rely upon it in our everyday life and it serves us well in lots of areas. But because “every moment in the market is unique” it serves us less well there.]

Thus, Hume’s two problems of induction were:

1) The logical problem: Are we rationally justified in reasoning from repeated instances of which we have had experience to instances of which we have had no experience?

Hume’s unrelenting answer was: No, we are not justified, however great the number of repetitions may be. [The point here again each moment in the market is unique; it’s may rhyme with the past, but there are differences.]

And Hume added it did not make the slightest difference if, in this problem, we ask for the justification not of certain belief, but of probable belief. Instances of which we have had experience do not allow us to reason or argue the probability of instances of which we have had no experience, any more than to the certainty of such instances.

2) The following psychological question: How is it that nevertheless all reasonable people expect and believe that instances of which they have had no experience will conform to those of which they have had experience? Or in other words, why do we all have expectations, and why do we hold on to them with such great confidence, or such strong belief?

Hume’s answer to this psychological problem of induction was: Because of custom or habit; or in other words, because of the irrational but irresistible power or the law of association. We are conditioned by repetition; a conditioning mechanism without which, Hume says, we could hardly survive.

Okay! I realize this is getting thick, hang in there, almost there.

Popper agreed with the first part of what Hume talked about; the logical problem. But Popper, couldn’t accept the irrationality of the second part—the psychological problem.

It is here where we get to the black swan. Popper posed that yes we must use experience of past instances to advance our knowledge but we must accept the fact that just because so many past instances were effectively consistent, or the same, it does not therefore mean a theory based upon those past instances has been proven. The reason he says this is because there may be some future instance out there which invalidates all that has come before it, and it only takes one such instance to do that. Therefore, all theories can be falsified, but they cannot be proven simply by past experience.

…Or in other words, from a purely logical point of view, the acceptance of one counter instance to the view that, “All swans are white,” implies the falsity of the law “All swans are white”— that law, that is, whose counter instance we accepted. Induction is logically invalid; but refutation or falsification is a logically valid way of arguing from a single counter instance to—or, rather, against—the corresponding law.

This logical situation is completely independent of any question of whether we would, in practice, accept a single counter instance for example, a solitary black swan in refutation of a so far highly successful law. I do not suggest that we would necessarily be so easily satisfied. We might well suspect that the black specimen before us was not a swan. And in practice, anyway, we would be most reluctant to accept an isolated counter instance. But this is a different question. Logic forces us to reject even the most successful law the moment we accept one single counter instance. [Thus, can there ever be a market “theory”?]

The theory, or law, that all swans were white was falsified once a black swan living in Australia was discovered. Till then, everyone knew all swans were white. Done deal!

Of course, everyone knew Triple AAA-rated tranches of securities were safe—they had been in the past. Everyone knows municipal bonds will be fine because the default rate has always been low in the past. Everyone knows that gold is the only real money. Everyone knows inflation is a monetary phenomenon. Everyone knows the dollar must go down. Everyone knows that China will rule the world soon.

We could go on and on into infinitum with what everyone thinks they know. But interestingly, the things we seem to think we know often don’t even have the consistent instances of induction in their favor. We cling to ideas in the financial world that have been falsified before but seem to gather a second life. This isn’t even close to the word logical. But customs and habits are powerful motivators.

The Sufi summarizes Popper

“There is an old Sufi tale about a mullah (Nasruddin) who was discovered by a passer-by searching in the dust outside his house. What was he looking for, the stranger inquired? A key, said the mullah. Where did he drop it? “In the house” replied the mullah. Then why was he looking in the dust outside? Because here he was in bright sunlight, whereas in the house it was dark and difficult to see.

“It happens to us all the time. The solution to worthwhile problems is never out there in the open. The key to financial markets is elusive. It must be so, by definition. The price-discounting mechanism ensures that the majority are always looking out there in broad daylight, when the key is somewhere else, in the shadow.

John Percival, The Way of the Dollar

Identifying the divers of currencies is quite elusive.

“Finally, one had to see if there were other relationships which had any predictive value for currencies like inflation, trade, money supply, oil prices, economic growth, et al. So far, the conclusion is that few such relationships and none of the relationships that most observers seem to rely on are useful for predicting the dollar

John Percival, The Way of the Dollar

I think this is where the trend followers get it right. They don’t try to explain all (or any) of the reasons why prices are heading in a certain direction; they simply want to “ride the bucking bronco” for all its worth, to quote Dunn Capital Management’s founder Bill Dunn.

So, we started off with a seemingly simple and sensible equation. But in this short time, I think I have shown it is neither simple nor sensible.

So where does this leave us?

I am not sure where it leaves you. But it leaves me with a few conclusions:

“It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” ― Yogi Berra

1. Currency trading, unlike other asset classes, is primary a sentiment-driven vehicle. Sentiment analysis should be the primary focus of currency analysis. [Tao of Markets]

And though we should monitor things like yield differential and economic growth and capital flows closely, we should not attempt to forecast that stuff. Let others do all the forecasting. We need only concentrate on two things: 1) the consensus rational and 2) potential for surprise to the consensus rationale.

“Our success or failure will rest on our ability to anticipate prevailing expectations and not real-world developments.” – George Soros, The Alchemy of Finance

2. If what you are doing (your edge) works for you, then don’t let anyone tell you what you are doing is flawed.

The upshot: Avoid, or at least be very suspect, of those who hold themselves out as experts. Experts, or gurus, have no better handle on what the future will hold than you do. The difference is the experts make a lot more predictions about the future; then they selectively highlight the ones which panned out; the ones that didn’t they hope will slide down the memory hole.

Our guesses about the future have been working out well lately. Our positioning (below) was primary based on our expectation the crowd was becoming too bearish on the dollar (sentiment)…

Sign Up for Black Swan Forex Free Week

If you would like to sample the Black Swan Forex service, simply send us your name and email address and we will set up with full access to our service.

Here is an explanation of our trading style and methodology used to generate ideas for our customers.

Thank you.

Regards,

Jack Crooks

Black Swan Capital www.blackswantrading.com

Phone: 772-349-6883

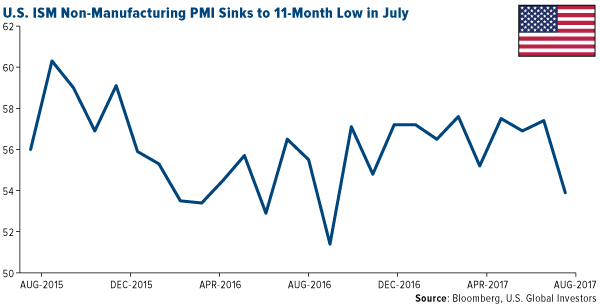

In July, the Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) Non-Manufacturing Index fell to an 11-month low of 53.9, 3.5 points below its June reading of 57.4. The index measures the non-manufacturing, services industries such as food services, education, real estate, health care and more.

Economists had expected a reading closer to 56.9, so it’s safe to call this a disappointment. Although the index is still above the key 50 threshold, where it’s held for 91 straight months now, the slowdown suggests that “the economy may have lost some momentum going into the third quarter,” as Capital Economics’ Andrew Hunter said in a note last week.

Following this report, it’s possible we’ll see the U.S. dollar rally before pulling back even further. Having hit a 15-month low last week, the dollar looks oversold and ready for a “retracement,” as CLSA’s Christopher Wood put it.

“It remains remarkable how weak the dollar has been so far this year given the Fed’s surprisingly hawkish rhetoric and given that its latest statement last week still suggests that the American central bank intends to commence balance sheet contraction next quarter,” Wood wrote in the latest “GREED and fear.”

I’ll have more to add on the Fed’s balance sheet later.

I’ll have more to add on the Fed’s balance sheet later.

July was the dollar’s fifth consecutive month of losses, the longest such stretch since December 2010 through April 2011. As I said in a Frank Talk last week, the major contributing factor to the greenback’s slide is political uncertainty surrounding President Donald Trump and Congress. Not only did the Obamacare repeal and replace bill fail (again), but Trump’s White House continues to look like a revolving-door workplace, with the foul-mouthed Anthony Scaramucci pushed out as communications director last week after only 10 days on the job. This reportedly came at the urging of brand new chief of staff John Kelly, who recently replaced Reince Priebus.

But it’s no secret that Trump favors a weaker currency. Since he declared that the dollar was “getting too strong” back in April, it’s lost close to 8 percent of its value against a basket of several other currencies. Add to this the disappointing ISM report, weakening automobile sales and slightly lower-than-hoped-for GDP growth in the second quarter, and it seems less and less likely we’ll see more than one additional rate hike in 2017.

Economic Growth Revised Down

On Friday, the Labor Department announced the U.S. economy added a robust 209,000 jobs in July, beating the consensus, while the unemployment rate dropped even further to a 16-year low of 4.3 percent.

Wage growth, however, remained pretty flat, which is a concern. Consumption is the number one driver of economic growth in the U.S., and if American workers aren’t getting raises, they’re not spending more.

All of this is spurring some economists to rethink their U.S. growth estimates. In its World Economic Outlook for July, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) revised down its domestic economic growth forecast, from 2.3 percent to 2.1 percent in 2017, and from 2.5 percent to 2.1 percent in 2018. The Washington-based fund attributes this revision to “the assumption that fiscal policy will be less expansionary than previously assumed, given the uncertainty about the timing and nature of U.S. fiscal policy changes.”

IMF economists, in other words, have doubts that tax reform, deregulation or an infrastructure package will be coming anytime soon.

We’ll see if they’re right. After the August recess, Congress plans to tackle tax reform, which the U.S. sorely needs. I hope lawmakers can come together and pass a comprehensive bill this fall that will deliver some relief to American workers, families and corporations.

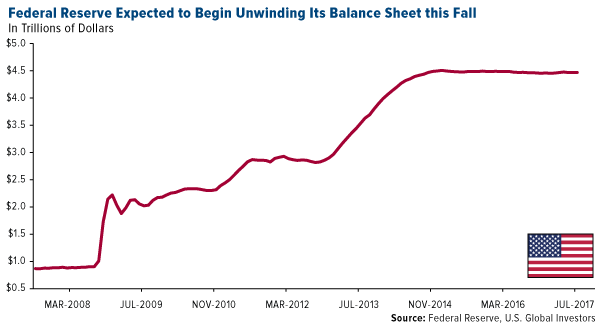

Fed to Take Away the Punchbowl

Big changes could be coming on the monetary side this fall as well. In an address to the Economic Club of Las Vegas last week, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco John Williams said the Fed will likely begin the process of monetary normalization as soon as next quarter. This includes unwinding the Fed’s $4.5 trillion balance sheet, composed of long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The process could take up to four years to complete.

Now that “we’ve finally recovered from the recession,” Williams said, it’s time for the private and public sectors to “step up and take the lead in making the investments and enacting policies needed to improve the longer-term prospects of our economy and society.”

I agree 100 percent. For nearly 10 years now we’ve seen an imbalance in monetary and fiscal policies, with the economy and stock market being propped up by cheap credit.

There’s a historical risk in the Fed reducing its balance sheet, though. The central bank has embarked on this reduction six times in the past—in 1921-1922, 1928-1930, 1937, 1941, 1948-1950 and 2000—and all but one episode ended in recession.

That’s according to research firm MKM Partners, whose chief economist, Mike Darda, urged attendees of a Fidelity event in May to hope for the best but prepare for the worst.

“My opinion is that business cycles don’t just end accidentally,” Darda said. “They are killed by the Fed. If the Fed tightens enough to induce a recession, that’s the end of the business cycle.”

“My opinion is that business cycles don’t just end accidentally,” Darda said. “They are killed by the Fed. If the Fed tightens enough to induce a recession, that’s the end of the business cycle.”

So how can investors prepare?

“Obviously, diversification is important,” Darda said, highlighting municipal bonds and emerging markets. “But my focus there would be on the commodity-importing emerging markets.”

Fidelity’s Julian Potenza seconded Darda’s emphasis of muni bonds, saying “investors should consider keeping the portion of their fixed-income portfolio that is currently earmarked for liquidity relatively short, in terms of duration.”

Indeed, shorter-duration, tax-free munis have a history of delivering positive returns even during economic downturns and in environments of rising and lowering interest rates.

As for emerging markets, CLSA reported last week that international ETF inflows so far this year are outpacing domestic U.S. ETF inflows, $103 billion to $86 billion. The brokerage and investment firm recommended an overweight position in emerging markets, specifically Europe ex-U.K.

Tech Stocks a Third of Market Gains in 2017

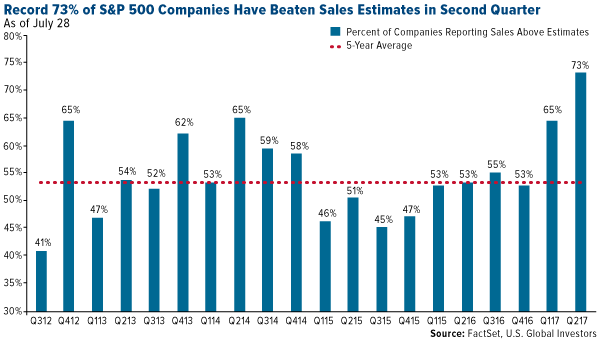

For the second quarter, close to a record 75 percent of S&P 500 Index companies are beating not just sales estimates but also earnings per share (EPS) estimates, according to FactSet data. What’s more, they’re beating these estimates by wider margins than historical second-quarter averages.

Granted, only around 60 percent of companies have reported as of this writing, but the news is impressive nonetheless.

How much of this is due to euphoria over Trump’s pro-growth fiscal agenda, and how much to a weakening U.S. dollar? That’s difficult to say, but no one can argue the fact that American multinationals are benefiting from a weaker dollar, which makes their exports more competitive globally. Apple, which generated 61 percent of its revenue from foreign markets in the second quarter, just reported an all-time quarterly services revenue record. “Services,” which includes Apple Music, iTunes, iCloud and Apple Pay, brought in an astounding $7.3 billion, up from $6 billion during the same quarter last year.

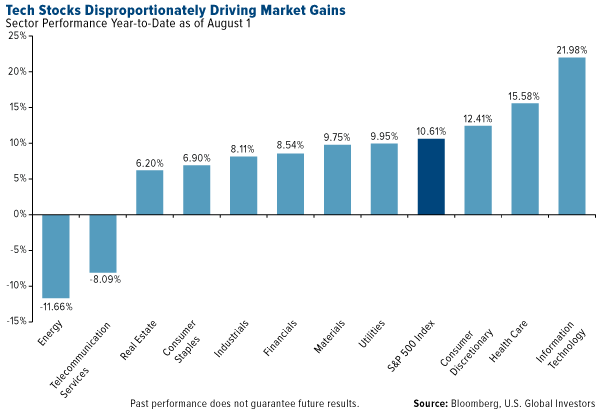

Speaking of Apple, it’s one of only five U.S. stocks that, together, are responsible for a third of the market’s gains in 2017, the other four being Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft and Alphabet (Google). As you can see below, information technology is up close to 22 percent year-to-date, followed by health care at 15.5 percent.

The reason I share this with you is because, while the market appears to be seeing solid growth right now, it’s being propelled disproportionately by only a handful of tech stocks. The S&P 500 is up 10.6 percent, but if we remove information technology, it’s up only around 7.5 percent. This makes the market vulnerable, should those stocks see a correction.

And that’s why I believe it’s particularly important to stay diversified, as Mike Darda said—diversified in emerging markets, which offer attractive valuations; muni bonds; and, as always, gold and gold stocks.

Job approval numbers for Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe are in freefall. Abe’s support has now fallen below 30%, and his Liberal Democratic Party recently suffered heavy losses stemming from a slew of scandals revolving around illegal subsidies received by a close associate of his wife. But as we have seen back on this side of the hemisphere, the public’s interest in these political scandals can be easily overlooked if the underlying economic conditions are favorable. For instance, voters were apathetic when the House introduced impeachment proceedings at the end of 1998 against Bill Clinton for perjury and abuse of power. And Clinton’s perjury scandal was indefensible upon discovery of that infamous Blue Dress. The average citizen, then busily counting their chips from the dot-com casino, were disinterested in Clinton’s wrongdoings because the 1998 economy was booming. Clinton remained in office, and his Democratic party gained seats in the 1998 mid-term elections.

Therefore, Abe’s scandal is more likely a referendum on the public’s frustration with the failure of Abenomics.

When Shinzo Abe regained the office of Prime Minister during the last days of 2012, he brought with him the promise of three magic arrows: an image borrowed from a Japanese folk tale that teaches three sticks together are harder to break than one. The first arrow targeted unprecedented monetary easing, the second was humongous government spending, and the third arrow was aimed at structural reforms. The Prime Minister assured the Japanese that his “three-arrow” strategy would rescue the economy from decades of stagnation.

Unfortunately, these three arrows have done nothing to improve the life of the average Japanese person. Instead, they have only succeeded in blowing up the debt, wrecking the value of the yen and exploding the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) balance sheet. For years Japanese savers have not only seen their yen denominated deposits garner a zero percent interest rate in the bank; but even worse, have lost purchasing power against foreign currencies. The yen has lost over 30 percent of its value against the US dollar since Abe regained power in 2012.

Meanwhile, the Japanese economy is still entrenched in its “lost-decades” morass; and growing at just over one percent year over year in Q1 2017. Japan’s dramatic slowdown in growth, which averaged at an annual rate of 4.5 percent in the 1980s, fell to 1.5 percent in the 1990s and never recovered. In addition to this, higher health care costs from an aging population have driven government health care spending to move from 4.5 percent of GDP in 1990, to 9.5 percent in 2010, according to IMF estimates.

Incredibly, this low-growth and debt-disabled economy has a 10-Year Note that yields around zero percent; thanks only to BOJ purchases.

Prime Minister Abe’s plan to address this recent scandal-driven plummet in the polls is to increase government spending even more and have the BOJ simply step up the printing press. In other words, he is going to double down on the first two arrows that have already failed! However, the Japanese people appear as though they have now had enough.

Japan’s National Debt is already over a quadrillion yen (250% of GDP). And the nation would never be able to service this debt if the BOJ didn’t own most of it. The sad truth is that the only viable alternative for Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) is an explicit or implicit default. And, a default of the implicit variety has already occurred because the BOJ now owns most of the government debt—total assets held by the BOJ is around 93% of GDP; JGBs equal 70% of GDP.

Japan is a paragon to prove that no nation can print, borrow and spend its way to prosperity. Abenomics delivered on all the deficit spending that Keynesians such as Paul Krugman espouse. But where is the growth? Japanese citizens are getting tired of Abenomics and there are some early indications that they may vote people in power that will force the BOJ into joining the rest of the developed world in the direction of normalizing monetary policy.

The reckless policies of global central banks have left investors starving for yield and forcing them out along the risk curve. But interest rates are set to rise as central banks remove the massive and unprecedented bid on sovereign debt—perhaps even in Japan. A chaotic interest rate shock wave is about to hit the global bond market, which will reverberate across equity markets around the world. Is your portfolio ready?

By Michael Pento

Policy across the U.S. is changing fast since the election of President Trump. And natural resource companies have already begun to benefit from the shift.

Policy across the U.S. is changing fast since the election of President Trump. And natural resource companies have already begun to benefit from the shift.

Now two more major measures have just come down — which could open big opportunities for mining and energy in the U.S.

The Department of Interior yesterday unveiled a raft of new policies. One of the biggest being a rollback of Obama-era regulations put in to protect wildlife.

Specifically, the sage grouse. A bird that resides in several prime mining and petroleum jurisdictions — particularly in western U.S. states such as Nevada.

The Obama administration had brought in federal protection for the sage grouse. Including strict rules on land use in areas where the bird resides — which had threatened to withdraw large tracts of land from mineral development and oil and gas drilling.

But the Department of Interior has now directed that several changes be made to that legislation. With officials saying the revised rules will attempt to strike a balance between preservation and economic opportunities.

The biggest change will be allowing state agencies to grant exemptions to the federal legislation. Which could allow local lawmakers to approve extractive activities in places that would have previously been off limits.

And that wasn’t the only big change made by Interior. With officials also also reversing another Obama administration policy — one that had reformed royalties paid by coal and petroleum developers on federal lands across the U.S.

The revised rules had closed loopholes that critics say resource firms were using to dodge tax payments. But industry had complained that the new measures were unnecessarily complex, impeding development of new projects.

Those rules will now be rendered void — with the royalty system reverting to the old regime as of early September. Watch for all of these shifts to help spur project activity across America, particularly in the coal sector — which should now see improved profitability.

Here’s to the times a-changing,

Dave Forest

dforest@piercepoints.com

Below you can see that commercial hedgers in the crude oil market are back at one of the highest net short positions in history.

Below you can see that commercial hedgers in the crude oil market are back at one of the highest net short positions in history.

also from King World:

Greenspan, Stagflation And What It Means For Commodities, Gold & Silver