Personal Finance

Employment is one of the most important factors impacting the value of real estate investments in B.C., so it is worth a closer look at some of the recent news.

It was reported this morning that B.C. gained 6,200 jobs in August versus a loss of 11,700 in July. So, that equates to a net loss of 5,500 jobs over the summer. B.C.’s unemployment rate for August was at 6.6%, the same level it was at in August 2012. (It should also be pointed out that the jump in jobs in August was driven primarily by part-time employment which is not overly encouraging).

This is in contrast to the media coverage over the last couple of days about the growing demand for “trade” jobs in the province. These stories focused on the demand for trades people in the middle part of B.C. and how this has led to an overflow of applicants for trades training both at the high school and post-high school levels. BCIT is even considering “round-the-clock” classes to meet the influx!

Anecdotally, I have also witnessed the increased number of trades people, primarily construction, gathering for work in the downtown core as I walk to the office everyday around 6:00am.

So, employment in B.C. looks hot anecdotally, but looks rather anemic statistically. Why is that the case?

Well, I have a theory.

The visible growth in jobs – in the trades – is the result of increased investment spending. This is driven by historically low interest rates which are the result of global economic policies and forces. Also, for an economy, high-paying trades jobs are trophy jobs. They are going to get attention from local politicians and media.

The less visible area of the job market – part-time and lower-paid service sector employment – is waning because of a lack of growth in the underlying economy. Hiring costs, taxes, fees, tolls, cost of living, and real estate prices that have increased in B.C. over the last decade have burdened the economy. Additionally, over the last decade, growth in public-sector employment was dramatic, but that is no longer a growth engine because the province’s public sector payroll had become disproportionately large relative to the size of the provincial economy.

Overall, the province is treading water with respect to employment. Additionally, and somewhat concerning, the high-profile growth in the trades has been dependent on easy global monetary policies that have kept a lid on interest rates and have spurred visible investment spending. However, despite those policies, longer term market-determined interest rates have begun to move higher, increasing about 1.5% over the last year. As a result, there is a risk that it may only be a matter of time until investment spending falls which will make the employment situation in the trades look more like the employment situation elsewhere in B.C.

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson GMP Limited or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author’s judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Richardson GMP Limited, Member Canadian Investor Protection Fund.

Richardson is a trade-mark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trade-mark of GMP Securities L.P. Both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited.

The report says Canada’s housing market is the second-most expensive among 19 nations surveyed when measured by price-to-rent, and among the top three when it comes to price-to-income.

“If these ratios are higher than their historical averages … property is overvalued; if they are lower it is undervalued. On this basis, Canada’s house prices are bubbly whereas Japan’s are undeservedly flat,” the magazine said in its latest issue.

Canada’s Baby Boomers have some major catching up to do if they want to meet their retirement goals, says a new study.

Canada’s Baby Boomers have some major catching up to do if they want to meet their retirement goals, says a new study.

Boomers are, on average, $400,000 short of their $658,000 nest egg retirement goal, according to the survey by the BMO Wealth Institute.

Canadian retail sales fell a surprisingly large 0.6 per cent in June to $40.1 billion, partially offsetting a large gain in May, as consumers pulled back from purchases of a wide range of products, according to Statistics Canada data.

“Canadian consumers fared a bit worse than expected,” CIBC World Markets economist Emanuella Enenajor said in a research note, noting a 0.8 per cent decline when auto sales are excluded.

Albert Einstein, a man who knew a thing or two about celestial mechanics, supposedly once called compound interest “the most powerful force in the universe.” While the remark was likely meant to be funny (astrophysicists can be hilarious), it sheds light on the often overlooked fact that small changes, over time, can yield enormous results. Over eons, small creeks can carve large canyons through solid rock. The same phenomenon may be at work in our economy. A minor, but persistent under bias in the inflation gauge used in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) may have created a wildly distorted picture of our economic health.

It would be impossible to measure the economy without “backing out,” inflation. That is why economists are very careful to separate GDP reports into two categories: “nominal” (which are not adjusted for inflation), and real (which are). Only the real reports matter. The big question then becomes, how do we measure inflation? Just as I reported last week with respect to the biases baked into the government’s GDP revisions, the devil is in the details.

As it turns out there are a number of official inflation gauges that vie for supremacy. Most people tend to follow the Consumer Price Index (CPI) which is compiled by Bureau of Labor Statistics, a division of the Department of Labor. The CPI is regarded as the broadest measurement tool, but it has been changed many times over the years. Most famously, its formulas were loosened in the late 1990’s as a result of the “Boskin Commission” which said that the CPI overstated inflation by failing to account for changes in consumer behavior. I believe those changes seriously undermined the reliability of the index. But the CPI itself has to contend for relevance with its stripped down rival, the “Core CPI,” which factors out food and energy, which many believe are too volatile to be accurately counted. The core CPI is almost always lower than the “headline” number.

Another set of inflation data, the “GDP Deflator” is compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (part of the Commerce Department), and is used by them to calculate GDP. The deflator differs from the CPI in that it has much more flexibility in weighting and swapping out items that are in its sample basket of goods and services. While the CPI attracts the lion’s share of the media and political attention, it is the deflator that is relevant when looking at economic growth.

On a quarterly basis the two numbers are usually close enough to escape scrutiny. (However, the most recent 2nd quarter GDP estimates relied on annualized inflation of a ridiculously low .7%!). But if you look at a broader time horizon a very clear pattern emerges that makes a great difference in how we perceive the economic landscape.

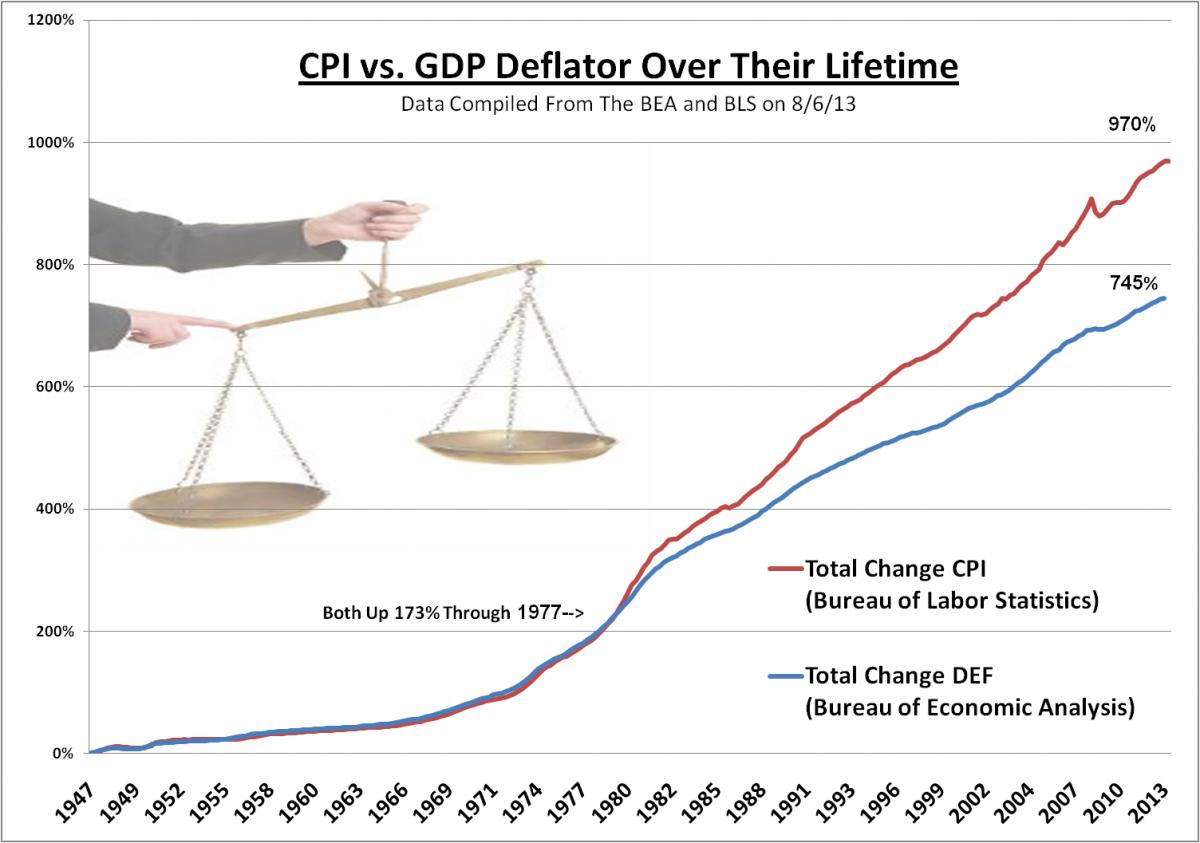

Available data sets for both the CPI and the GDP deflator go back to 1947. That 66 year period falls neatly into two phases. From 1947 to 1977 both yardsticks moved together almost identically, both rising 173% over that time. But in the ensuing 36 years (until 2013), the CPI is up almost three fold (292%) while the deflator is only up about two fold (209%). The CPI rising 40% more than the GDP deflator is an extremely significant factor. How did that happen? As it turns out, quarterly inflation assumptions have been, on average, .17% lower for the deflator than for the CPI since 1977. That is a small number. But as with compound interest small numbers add up to big numbers over time.

Annualized the .17% difference would shave off an additional .68% of annual GDP growth. This is about a quarter of the average 2.85% real growth rate since 1977 that the government has calculated using the deflator. Over 35 years this has likely made a huge difference in the how the economy actually feels and how we live, regardless of the nominal figures that are published. Even if you were to split the difference between the CPI and the deflator you would still get an economy that feels significantly smaller than it appears.

The $64,000 question ($188,000 adjusted by CPI inflation since 1977) is what happened in 1977 to make the CPI and the deflator diverge? Sadly, the details aren’t really made public. What we do know is that the BEA took over the task in 1972, and that the separation occurred a few years later when inflation really started to run out of control. We also know that the deflator is more flexible than the CPI and that the interests of the government are better served by reporting low inflation and higher growth. So in other words, the deflator is likely lower for the same reasons that dogs lick themselves in intimate places: because they want to and they can.

If we had been growing as quickly as the official GDP indicates, why would our labor force have contracted so significantly? Why are we continuously replacing middle class jobs with lower paying ones? Why would we be using 3 percent less energy nationally than we did 10 years ago despite an 8.8% growth in population? Why would Americans be spending a higher percentage of their disposable incomes on basic necessities than they were 10 years ago? These trends don’t conform to healthy GDP growth. So maybe the growth is largely an illusion?

When you take into consideration the likelihood that even the CPI drastically understates inflation, you get a much clearer picture of the true state of the U.S. economy. If you ever wondered how we went from being the world’s largest creditor to its biggest debtor despite all this economic growth, now you know. As the growth was merely a statistical illusion, we have been forced to borrow money to maintain a life style our economy can no longer support.

So the next time you see a GDP report remind yourself that the “deflator” should really be called the “distractor.” It’s there to distract you from the truth.

Peter Schiff is the CEO and Chief Global Strategist of Euro Pacific Capital, best-selling author and host of syndicated Peter Schiff Show.

Subscribe to Euro Pacific’s Weekly Digest: Receive all commentaries by Peter Schiff, John Browne, and other Euro Pacific commentators delivered to your inbox every Monday!

To order your copy of Peter Schiff’s latest book, The Real Crash: America’s Coming Bankruptcy – How to Save Yourself and Your Country, click here.

For in-depth analysis of this and other investment topics, subscribe to Peter Schiff’s Global Investor newsletter. CLICK HERE for your free subscription.