Wealth Building Strategies

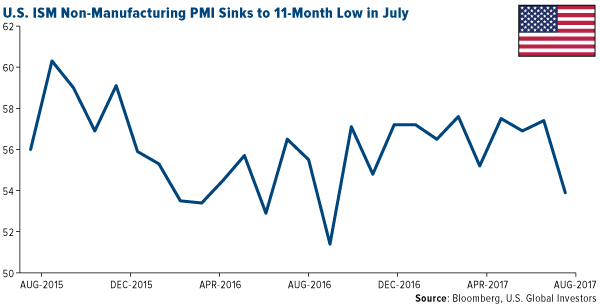

In July, the Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) Non-Manufacturing Index fell to an 11-month low of 53.9, 3.5 points below its June reading of 57.4. The index measures the non-manufacturing, services industries such as food services, education, real estate, health care and more.

Economists had expected a reading closer to 56.9, so it’s safe to call this a disappointment. Although the index is still above the key 50 threshold, where it’s held for 91 straight months now, the slowdown suggests that “the economy may have lost some momentum going into the third quarter,” as Capital Economics’ Andrew Hunter said in a note last week.

Following this report, it’s possible we’ll see the U.S. dollar rally before pulling back even further. Having hit a 15-month low last week, the dollar looks oversold and ready for a “retracement,” as CLSA’s Christopher Wood put it.

“It remains remarkable how weak the dollar has been so far this year given the Fed’s surprisingly hawkish rhetoric and given that its latest statement last week still suggests that the American central bank intends to commence balance sheet contraction next quarter,” Wood wrote in the latest “GREED and fear.”

I’ll have more to add on the Fed’s balance sheet later.

I’ll have more to add on the Fed’s balance sheet later.

July was the dollar’s fifth consecutive month of losses, the longest such stretch since December 2010 through April 2011. As I said in a Frank Talk last week, the major contributing factor to the greenback’s slide is political uncertainty surrounding President Donald Trump and Congress. Not only did the Obamacare repeal and replace bill fail (again), but Trump’s White House continues to look like a revolving-door workplace, with the foul-mouthed Anthony Scaramucci pushed out as communications director last week after only 10 days on the job. This reportedly came at the urging of brand new chief of staff John Kelly, who recently replaced Reince Priebus.

But it’s no secret that Trump favors a weaker currency. Since he declared that the dollar was “getting too strong” back in April, it’s lost close to 8 percent of its value against a basket of several other currencies. Add to this the disappointing ISM report, weakening automobile sales and slightly lower-than-hoped-for GDP growth in the second quarter, and it seems less and less likely we’ll see more than one additional rate hike in 2017.

Economic Growth Revised Down

On Friday, the Labor Department announced the U.S. economy added a robust 209,000 jobs in July, beating the consensus, while the unemployment rate dropped even further to a 16-year low of 4.3 percent.

Wage growth, however, remained pretty flat, which is a concern. Consumption is the number one driver of economic growth in the U.S., and if American workers aren’t getting raises, they’re not spending more.

All of this is spurring some economists to rethink their U.S. growth estimates. In its World Economic Outlook for July, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) revised down its domestic economic growth forecast, from 2.3 percent to 2.1 percent in 2017, and from 2.5 percent to 2.1 percent in 2018. The Washington-based fund attributes this revision to “the assumption that fiscal policy will be less expansionary than previously assumed, given the uncertainty about the timing and nature of U.S. fiscal policy changes.”

IMF economists, in other words, have doubts that tax reform, deregulation or an infrastructure package will be coming anytime soon.

We’ll see if they’re right. After the August recess, Congress plans to tackle tax reform, which the U.S. sorely needs. I hope lawmakers can come together and pass a comprehensive bill this fall that will deliver some relief to American workers, families and corporations.

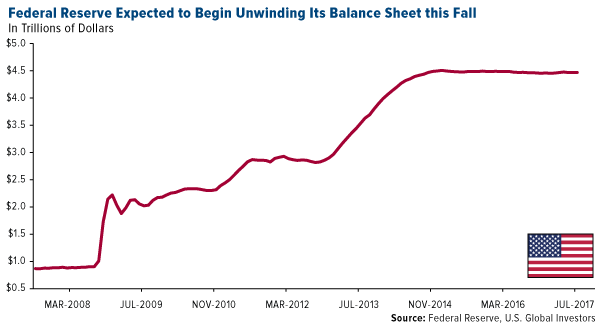

Fed to Take Away the Punchbowl

Big changes could be coming on the monetary side this fall as well. In an address to the Economic Club of Las Vegas last week, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco John Williams said the Fed will likely begin the process of monetary normalization as soon as next quarter. This includes unwinding the Fed’s $4.5 trillion balance sheet, composed of long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The process could take up to four years to complete.

Now that “we’ve finally recovered from the recession,” Williams said, it’s time for the private and public sectors to “step up and take the lead in making the investments and enacting policies needed to improve the longer-term prospects of our economy and society.”

I agree 100 percent. For nearly 10 years now we’ve seen an imbalance in monetary and fiscal policies, with the economy and stock market being propped up by cheap credit.

There’s a historical risk in the Fed reducing its balance sheet, though. The central bank has embarked on this reduction six times in the past—in 1921-1922, 1928-1930, 1937, 1941, 1948-1950 and 2000—and all but one episode ended in recession.

That’s according to research firm MKM Partners, whose chief economist, Mike Darda, urged attendees of a Fidelity event in May to hope for the best but prepare for the worst.

“My opinion is that business cycles don’t just end accidentally,” Darda said. “They are killed by the Fed. If the Fed tightens enough to induce a recession, that’s the end of the business cycle.”

“My opinion is that business cycles don’t just end accidentally,” Darda said. “They are killed by the Fed. If the Fed tightens enough to induce a recession, that’s the end of the business cycle.”

So how can investors prepare?

“Obviously, diversification is important,” Darda said, highlighting municipal bonds and emerging markets. “But my focus there would be on the commodity-importing emerging markets.”

Fidelity’s Julian Potenza seconded Darda’s emphasis of muni bonds, saying “investors should consider keeping the portion of their fixed-income portfolio that is currently earmarked for liquidity relatively short, in terms of duration.”

Indeed, shorter-duration, tax-free munis have a history of delivering positive returns even during economic downturns and in environments of rising and lowering interest rates.

As for emerging markets, CLSA reported last week that international ETF inflows so far this year are outpacing domestic U.S. ETF inflows, $103 billion to $86 billion. The brokerage and investment firm recommended an overweight position in emerging markets, specifically Europe ex-U.K.

Tech Stocks a Third of Market Gains in 2017

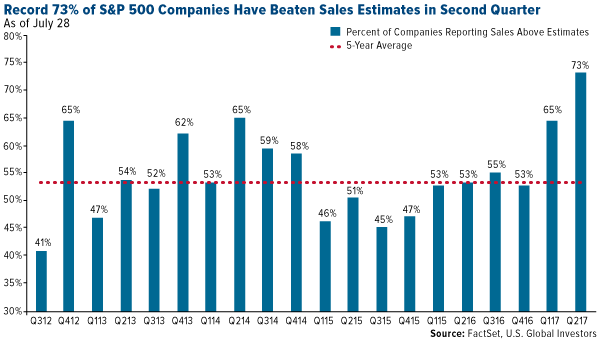

For the second quarter, close to a record 75 percent of S&P 500 Index companies are beating not just sales estimates but also earnings per share (EPS) estimates, according to FactSet data. What’s more, they’re beating these estimates by wider margins than historical second-quarter averages.

Granted, only around 60 percent of companies have reported as of this writing, but the news is impressive nonetheless.

How much of this is due to euphoria over Trump’s pro-growth fiscal agenda, and how much to a weakening U.S. dollar? That’s difficult to say, but no one can argue the fact that American multinationals are benefiting from a weaker dollar, which makes their exports more competitive globally. Apple, which generated 61 percent of its revenue from foreign markets in the second quarter, just reported an all-time quarterly services revenue record. “Services,” which includes Apple Music, iTunes, iCloud and Apple Pay, brought in an astounding $7.3 billion, up from $6 billion during the same quarter last year.

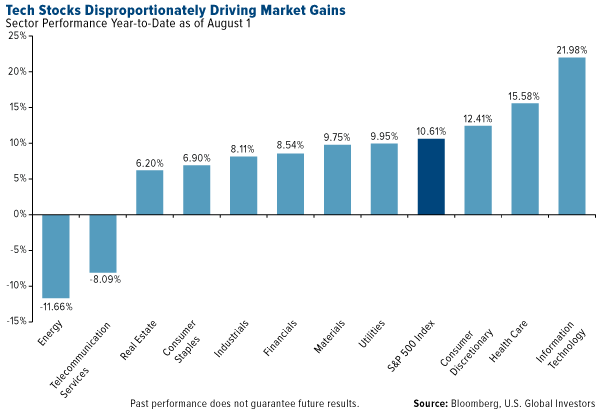

Speaking of Apple, it’s one of only five U.S. stocks that, together, are responsible for a third of the market’s gains in 2017, the other four being Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft and Alphabet (Google). As you can see below, information technology is up close to 22 percent year-to-date, followed by health care at 15.5 percent.

The reason I share this with you is because, while the market appears to be seeing solid growth right now, it’s being propelled disproportionately by only a handful of tech stocks. The S&P 500 is up 10.6 percent, but if we remove information technology, it’s up only around 7.5 percent. This makes the market vulnerable, should those stocks see a correction.

And that’s why I believe it’s particularly important to stay diversified, as Mike Darda said—diversified in emerging markets, which offer attractive valuations; muni bonds; and, as always, gold and gold stocks.

Summary

– Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Facebook, and Amazon are now the five largest U.S. market capitalization equities.

– Collectively their performance in 2017, the past three years, and the past decade has been amazing.

– They have also absorbed a tremendous amount of capital, sucking it away from other opportunities, and their run may be ending.

“A 60:40 allocation to passive long-only equities and bonds has been a great proposition for the last 35 years … We are profoundly worried that this could be a risky allocation over the next 10.” — Sanford C. Bernstein & Company Analysts (January 2017)

“Bull markets are born on pessimism, grow on skepticism, mature on optimism, and die on euphoria” — Sir John Templeton

Life and investing are long ballgames.” — Julian Robertson

Introduction

For active, value-orientated investors, the current bull market in U.S. stocks, which began in March of 2009, has been one of the most difficult bull markets to navigate in history. Said another way, it has not been anything like a day at the beach.

Keeping up with the market, without owning the five biggest market capitalization stocks, which are all large-cap growth stocks and listed in order of size, Apple (AAPL), Alphabet (GOOGL), Microsoft (MSFT), Facebook (FB), and Amazon (AMZN), has been nearly impossible.

A strong performance by the largest stocks spurred investors, speculators, and fund managers to allocate to these equities in ever-greater quantities, creating a self-reinforcing circle of buying exacerbated by the continued inflows into passive index funds and ETF funds.

So what is an investor to do?

The answer is that it may finally be time to step outside the black hole that is consuming a disproportionate amount of investor’s capital. Simply avoiding shares of AAPL, which I was bullish on previously, GOOGL, MSFT, FB, and AMZN could be one-key to investment outperformance over the next decade.

Thesis

The largest companies have consumed investor capital at an ever-increasing pace, forcing more and more investment managers to become closet indexers, closing active investment strategies, and creating a bigger opportunity for the remaining active investors.

The Five Biggest Are the Primary Culprits

Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Facebook, and Amazon have had extraordinary performance in 2017. AAPL shares are up 30% year-to-date, GOOGL shares have gained 21%, MSFT shares are up 19% in 2017, FB shares lead the pack with a remarkable 50% year-to-date gain, and AMZN shares are up a strong 36% even after their minor stumble Friday.

John Maynard Keynes once wrote what may be one of the most insightful observations on financial markets ever conceived:

John Maynard Keynes once wrote what may be one of the most insightful observations on financial markets ever conceived:

We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligence to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth, and higher degrees.

Now, what exactly is he talking about?

While it sounds like Keynes may have been practicing some rare form of martial arts, or Zen meditation, he was actually talking about financial markets … in particular, how to predict them.

Gold is the most misunderstood asset class in the financial world.

I remember when I first understood this and how enlightened I felt when I realized the true value of gold in one’s possession. I was 23 years old.

Because I was asked to speak at multiple conferences lately, I decided the time was right to explain the true nature and importance of gold in one’s portfolio, a concept that most modern investors simply do not understand or grasp.

Based on the responses I received after delivering this talk, it was evident the information I shared definitely struck a chord with those in attendance.

The information presented below is the content of my talk at those conferences. The first slide in my power point presentation was a quote.

Gold is the currency of monarchs,

Silver is the currency of the educated,

Barter is the currency of the working class, And Debt is the currency of slaves

Author Unknown

The second slide was this graphic below which was a statement that J.P. Morgan made while testifying before Congress in 1912.

Prepare for Turbulence

Prepare for Turbulence

Afraid of the Truth

We Couldn’t Take the Chance

Policy Brick Wall

Least-Bad at Best

Getting Out of Dodge

Global Contagion

Barefoot on the Beach

“The job of the central bank is to worry.”

– Alice Rivlin

“The central bank needs to be able to make policy without short-term political concerns.”

– Ben Bernanke Photo: Monica Muller via Flickr

“… from the standpoint of the overall economy, my bottom line is we’re watching it closely but it appears to be contained.

– Ben Bernanke, repeatedly, in 2007

“Would I say there will never, ever be another financial crisis? You know, probably that would be going too far, but I do think we’re much safer, and I hope that it will not be in our lifetimes, and I don’t believe it will be.”

– Janet Yellen, June 27, 2017

“My good friends, for the second time in our history, a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honor. I believe it is ‘peace for our time.’ Go home and get a nice quiet sleep.”

– Neville Chamberlain, September 30, 1938

The way we assess problems depends on our perspective. People can look at the same set of facts and reach quite different conclusions based simply on their circumstances. This is why it’s good at times to get away from your normal environment. Listen to a wide variety of opinions. Read books outside of your comfort zone. You’ll see things differently when you return.

I had that feeling on returning to the US from Shane’s and my honeymoon in St. Thomas. We’re now officially married, and we thank everyone for the congratulations and kind wishes. I saw a little bit of news while we were there but spent more time just relaxing with my bride and reading books.

Re-entering the news flow was a jolt, and not in a good way. Looking with fresh eyes at the economic numbers and central bankers’ statements convinced me that we will soon be in deep trouble. I now feel certain we will face a major financial crisis, if not later this year, then by the end of 2018 at the latest. Just a few months ago, I thought we could avoid a crisis and muddle through. Now I think we’re past that point. The key decision-makers have (1) done nothing, (2) done the wrong thing, or (3) done the right thing too late.

Having realized this, I’m adjusting my research efforts. I believe a major crisis is coming. The questions now are, how severe will it be, and how will we get through it? With the election of President Trump and a Republican Congress, your naïve analyst was hopeful that we would get significant tax reform, in addition to reform of a healthcare system that is simply devastating to so many people and small businesses. I thought maybe we’d see this administration cutting through some bureaucratic red tape quickly. With such reforms in mind I was hopeful we could avoid a recession even if a crisis developed in China or Europe.

Six months in, the Republican Congress that promised to repeal and replace Obamacare, cannot even agree on the process. For six years they discussed what to do, and you would think they might at least have a clue.

Tax reform? I’ve been talking with several of the Congressional leaders about tax reform, pointing out that without major tax reform this country is in danger of falling into a recession. No tinkering around the edges. Real change requires real change. There is now talk of having a tax bill of some kind ready to discuss in September and possibly pass in November, which, with this Congress, means that the process is likely to drift into next year sans a major push by the leadership. There is no consensus. No less an authority on the actual political process than Newt Gingrich wrote a very sharply worded column this week, declaring, “That legislative schedule is a recipe for disaster.” As Newt points out, if we are going to see any positive economic effect from tax reform, a bill has to be passed soon and implemented. Newt’s column was actually fairly discouraging to me. Knowing him as I do, I can tell you he wasn’t happy to have to write it. While I disagree with him on some of his tax-reform proposals, I agree that we need something significant and soon.

There has been some progress on the bureaucratic and regulatory fronts, but nowhere near what I’d expected. Appointments haven’t been made, and the bureaucracy is still in control of most of the levers of the economy.

I’d love to be wrong. Nothing would make me happier than having to eat all these words. But without significant changes, and soon, the economy will drift sideways and down. While second-quarter GDP growth will come in above 2%, the figure for the first six months of this year will remain below 2%. A host of indicators show a softening of the economy. For instance, , with a glut of more than 7 million previously leased cars clogging the auto market, new-car production is projected to continue to fall. Consumers are financially stretched, and credit card and student loan defaults have begun to rise. While there are bright spots, without major reforms the economy will drift lower, toward stall speed. Any outside shock – and several may be in the offing – could push us into recession.

And then we come to central banks.

One news item I didn’t miss on St. Thomas – and rather wish I had – was Janet Yellen’s reassurance regarding the likelihood of another financial crisis. Here is the full quote.

Would I say there will never, ever be another financial crisis? You know probably that would be going too far, but I do think we’re much safer, and I hope that it will not be in our lifetimes and I don’t believe it will be. [emphasis added]

I disagree with almost every word in those two sentences, but my belief is less important than Chair Yellen’s. If she really believes this, then she is oblivious to major instabilities that still riddle the financial system. That’s not good.

She may be right in that the future financial crisis will not look like the last financial crisis, at least in the United States. We have repealed the law passed under George W. Bush that allowed major banks to lever up 30 to 1. (What were they thinking?) We have required banks to recapitalize and to reduce their market-making activities in the bond market, theoretically reducing their risk of insolvency. And we have put in place all sorts of profitability- and productivity-reducing regulations. While these may be appropriate for larger financial institutions, they are choking the life out of smaller community banks, and thereby reducing the availability of capital to small businesses. Is it any wonder that we are seeing more businesses failing than being launched?

But like generals fighting the last war, central bankers will find that the next financial crisis will be fought on different fronts, with entirely different components and opponents. There is an appalling lack of liquidity and market-making available in the major fixed-income markets, something the banks used to provide, and now by regulatory statute they can’t. Oh, everything is just fine right now, but the moment we hit a speed bump, the liquidity and market-making capability that is left will simply dry up.

In theory, the Fed probably can’t provide liquidity for that type of market, but I will bet you a dollar to 47 doughnuts that they will find some loophole that authorizes them to step in somehow; otherwise there will be a spiral downward in the debt markets. Some markets will spiral up, and some will spiral down. We have once again created all kinds of new debt instruments as investors reach for yield in this low-rate environment, and there will simply be no market liquidity for them in a crisis. A flight to safety will ensure that long-term Treasury rates will plunge to levels that we have not yet seen.

I could list other imbalances in the financial markets, but you get the picture.

Financial politicians (which is what central bankers really are) have a long history of saying the wrong things at the wrong time. Far worse, they simply fail to tell the truth. Former Eurogroup leader Jean-Claude Juncker admitted as much: “When it becomes serious, you have to lie,” he said in the throes of Europe’s 2011 debt crisis.

They lie because they’re afraid of the impact the truth will have. This is a problem, because markets can’t function on false information, at least not indefinitely. The best thing for everyone is to let markets adjust naturally, even though confronting reality can mean short-term pain for some participants. And sometimes it does make sense to cushion the blow. It doesn’t make sense to cover over a problem for years, let it get bigger and bigger, and postpone acknowledging it until the worst possible time. Yet that’s what usually happens.

In fairness to the financial politicians, they often deal with situations where all the choices are bad. More often than not, that’s because their predecessors made similarly bad choices under similarly difficult conditions. The string of mistakes goes back decades. That is our situation today. We think governments and central banks are powerful, and they are in some ways, but they aren’t omnipotent. They don’t have monetary magic wands.

They also face enormous pressure to “do something,” even when the right thing is to do nothing and just let the market clear.

To understand what will be the mindset of central bankers all over the world during the next financial crisis, I can think of no better illustration than a debate that was conducted at the annual gathering of economists that David Kotok convenes in Maine in August. This debate provided an “aha!” moment, one that has been fundamental to my understanding of how central banks work in the midst of a crisis. Let’s rewind the tape to four years ago, when I wrote about that moment while it was still fresh in my mind.

On Saturday night David scheduled a formal debate between bond maven Jim Bianco and former Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee member David Blanchflower (everyone at the camp called him Danny)….

The format for the debate between Bianco and Blanchflower was simple. The question revolved around Federal Reserve policy and what the Fed should do today. To taper or not to taper? In fact, should they even entertain further quantitative easing? Bianco made the case that quantitative easing has become the problem rather than the solution. Blanchflower argued that quantitative easing is the correct policy. Fairly standard arguments from both sides but well-reasoned and well-presented.

It was during the question-and-answer period that my interest was piqued. Bianco had made a forceful argument that big banks should have been allowed to fail rather than being bailed out. The question from the floor to Danny was, in essence, “What if the Bianco is right? Wouldn’t it have been better to let banks fail and then restructure them in bankruptcy? Wouldn’t we have recovered faster, rather than suffering in the slow-growth, high-unemployment world where we find ourselves now?”

Blanchflower pointed his finger right at Jim and spoke forcefully. “It wasn’t the possibility that he was right that preoccupied us. We couldn’t take the chance that he was wrong. If he was wrong and we did nothing, the world would’ve ended, and it would’ve been our fault. We had to act.”

Blanchflower’s explanation made me realize that central bankers are quite human and so are their reactions in the middle of a crisis. They feel that they have to do something.

The present challenge arises because our central bank monetary heroes allowed QE, ZIRP, and in some places NIRP to persist far longer than was wise. You can make the case that these measures were necessary in 2008 and for a short period thereafter; but these policies should not have remained in place, much less been expanded, for 7-–9 more years. Yet they were. That this was a mistake is now clear to almost everyone. Iin hindsight. What to do about it is less clear.

On the positive side, our central bankers are talking about the problem. The kool kids’ new buzzword is policy normalization. Everyone (except the Bank of Japan) agrees that abnormality has outlived its usefulness. That’s important: Admitting your problem is the first step to solving it.

However, solutions are difficult when that first timid step runs you smack into a brick wall that you yourself built because you waited too long to act.

It was mid-2013 when Ben Bernanke first suggested the Fed might “taper” down its bond purchases. The Taper Tantrum ensued and stopped him from implementing the policy he clearly thought was right. It fell to Janet Yellen to implement the taper and then make one very tiny rate hike in December 2015. Another tantrum followed, this one centered in China. Plans to raise rates further were again postponed. As I noted in “Mad Hawk Disease” two weeks ago, Fed governors were clearly mindful of what would happen to the then-current Democratic administration if a policy error precipitated a recession. “We couldn’t take the chance.” They ignored Ben Bernanke’s admonition that “The central bank needs to be able to make policy without short-term political concerns.”

Now, with a Republican administration and Congress, the FOMC apparently feels no such concern about the potential for a policy error. We will never know, but I wonder if they would now be raising rates under a Clinton administration. It’s actually a serious question.

Having waited four years too long, the Fed, the ECB, and the Bank of England are finally tightening in a strange combination of caution and boldness. You may have heard public officials talk of being “cautiously optimistic.” The central bank version of that is “cautiously aggressive.” Each passing month makes them less cautious and more aggressive, it seems. Like kittens, they venture out from their mother gingerly at first but soon are romping underfoot and destroying furniture.

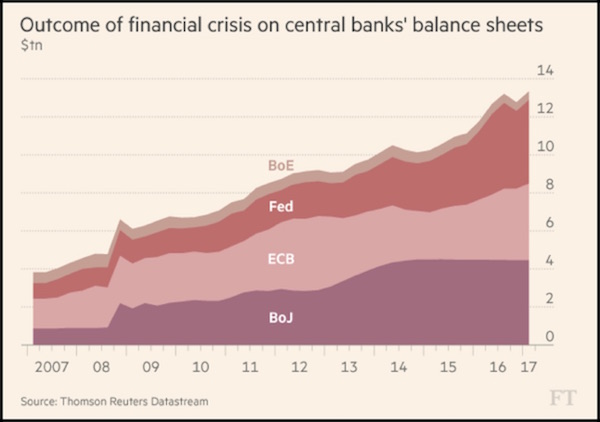

Source: Financial Times

That may be an amusing analogy, but reality is not amusing at all. The four largest central banks together have about $13 trillion on their balance sheets, a large portion of which they believe needs to roll off. Removing it without breaking something important will not be easy.

The central bankers are not unaware of this challenge. They have a conscience of sorts in the Bank of International Settlements, and it is whispering in their ears as loudly as it can. BIS economist Claudio Borio, in the institution’s annual report last month: “The end may come to resemble more closely a financial boom gone wrong, just as the latest recession showed, with a vengeance.”

The report’s monetary policy section was even more direct (emphasis mine):

Policy normalisation presents unprecedented challenges, given the current high debt levels and unusual uncertainty. A strategy of gradualism and transparency has clear benefits but is no panacea, as it may also encourage further risk-taking and slow down the build-up of policymakers’ room for manoeuvre.

That’s obvious, but it’s important that BIS said it. “Unprecedented challenges” may even understate the magnitude of what the Fed and other central banks are up against.

More from BIS:

In determining the pace of normalisation, central banks must indeed strike a delicate balance. On the one hand, there is a risk of acting too early and too rapidly. After a series of false dawns in the global economy, questions linger about the durability of this upswing. And the unprecedented period of ultra-low rates heightens uncertainty about reactions in financial markets and the economy.

On the other hand, there is a risk of acting too late and too gradually. If central banks fall behind the curve, they may at some point need to tighten more abruptly and intensively to keep the economy from overheating and inflation from overshooting. And even if inflation does not rise, keeping interest rates too low for long could raise financial stability and macroeconomic risks further down the road, as debt continues to pile up and risk-taking in financial markets gathers steam. How policymakers address these trade-offs will be critical for the prospects of a sustainable expansion.

I think that last part is too gentle. Financial-stability and macroeconomic risks are already elevated. Debt isn’t simply piling up; it’s up to the ceiling and pouring out the windows. Risk-taking in financial markets can hardly gather any more steam without blowing its top.

So yes, how policymakers address these trade-offs is indeed critical. But even if we assume our central bankers will act calmly and professionally – which perhaps we should not – the fact remains that they have no good options because they waited too long. “Least bad” is the best we can hope for, and I doubt we will get even that. The brick wall of bad decisions looms.

“Get out of Dodge” was a phrase made popular by Marshall Matt Dillon on the TV show Gunsmoke in the ’60s. The phrase slipped into the youth culture and endures as a shorthand way of saying that you’d better leave town before the stuff hits the fan.

I believe the Fed is aware that they should have been raising rates earlier. They also understand the present risks. While I believe it is appropriate to raise rates slowly, I simply cannot understand why they would want to reduce their balance sheet at this late date, at the same time that they jack up rates. They could have been letting the balance sheet roll off for four years, but to do so now in conjunction with raising rates simply increases the risk of a policy error. But I don’t think they will see that as their problem.

Chair Yellen and I both believe the majority of the current governors will be gone by the second quarter of next year. It would not surprise me at all if Vice-Chair Fischer offers to resign before his term is up in June 2018. This Fed is going to raise rates a few more times, start reducing the balance sheet, and then get the hell out of Dodge.

Federal Reserve governors basically have a 14-year term, which reduces the ability of any one president to appoint a majority of the FOMC within a four-year term. Of course, resignations affect the balance.

Trump is going to have the unusual opportunity to appoint at least six, and more likely seven, governors by the middle of next year, if not sooner. Whether he wants it to be or not, this will be the Trump Fed. Without major reforms in place, the Trump Fed will face a recession, serious global economic issues, and a resulting major equity bear market. Think they will continue to raise rates? How long before they start to talk about supplying a little more QE to appease the markets?

The current FOMC simply hopes that everything holds together until they can slip out the back way from Dodge. Who do you think will get the blame for the next crisis? It should be this FOMC, but that’s not the way the real world works.

The Trump Fed will be politicized and stigmatized by its Democratic opponents no matter what they do. Howls for outside controls and oversight will rise in the night.

The parlous state of the economy is not just an American problem, or a European or UK or Japanese or Chinese one. It is global.

I wonder whether Janet Yellen truly appreciates the degree to which Federal Reserve policy affects the entire world. Like it or not, the US dollar is the entire planet’s ultimate medium of exchange. One way or another, almost every financial transaction eventually settles in dollars. China and others would like to change that. Maybe they’ll succeed someday, but it won’t be this year or next.

That being the case, the way Fed policy impacts the dollar could make the inevitable crisis much worse. Looking only at the US, there’s a strong case for raising – oops, I mean “normalizing” – rates. Going to even 2% or 3% won’t kill our economy. But hiking rates will likely create other victims whose problems will soon become our problems, too.

Think of all the dollar-denominated debt owed by various emerging-market governments and businesses. Higher US rates will strengthen the dollar and make that debt costlier to service, almost certainly causing some defaults. In today’s highly leveraged markets, the pain caused by those defaults will quickly spread to lenders in Europe, Japan, and the US.

You might respond that more stringent capital requirements mean today’s banks are better able to withstand such scenarios. That’s partly true. It’s also true that the bank executives hate those requirements and are working assiduously to loosen them. These banks are also far larger than they were in 2008. Yes, they pass the Fed’s stress tests, but the Fed can’t test every possible adverse scenario. Generals always fight the last war. The next crisis probably won’t originate in residential mortgage loans. It will come from somewhere else, and we have no idea whether the banks are actually ready for it.

You and I can’t control whether banks are ready, but we can control whether we are ready. I am working on a number of fronts to help you. My brief time away convinced me beyond any doubt that a crisis of historic proportions is once again bearing down on us. We may have little time to prepare. We definitely have no time to waste.

As I mentioned at the beginning of the letter, Shane and I did get married on the beach in the Virgin Islands last week. We stayed at the fabulous Ritz-Carlton Hotel on St. Thomas, and I have to tell you it was one of the most pleasurable hotel/resort experiences of my life. At least for one week, we were living large. But it’s an important week, got to admit. The entire hotel team was fabulous; the venue was great; and the food was awesome. Highly recommended. And not just for getting married – we do hope to get back.

Your beginning to wonder if the nudge over the edge comes from our own central bank analyst,

John Mauldin

subscribers@MauldinEconomics.com