Wealth Building Strategies

Chinese stocks have dropped for four straight weeks to their lowest levels in seven months, following a government crackdown on financial leverage.

In fact, the Chinese policy-makers’ crackdown on leverage has already erased about $500 billion from the value of the Red Dragon’s stocks and bonds.

There’s no doubt in my mind that China’s credit boom was getting a little out of control. Take a look at this Bloomberg Intelligence chart.

You can clearly see that since 2008, China’s total debt as a percentage of GDP has skyrocketed – from about 160% in 2008 to almost 260% in 2016.

You read that right: China’s debt is 260% of GDP!

While I almost fell out of my chair when I read these latest stats, the fact is a government crackdown on China’s excessive leverage is long overdue.

Chinese authorities have implemented several measures to strengthen the country’s financial stability. In fact, China’s banking, insurance and securities regulators are all playing a part in the program.

I’m also happy to see that China is focusing much of their attention on the nation’s shadow-banking system. Shadow-banking assets increased by 21 percent in 2016 to the equivalent of $9.3 trillion, or 87 percent of gross domestic product, Moody’s Investors Service reported.

Getting these shadow-banking shenanigans under control means improved long-term economic stability for China as officials rein in the debt pile and improve financial transparency.

The short-term pain Chinese stocks are feel now should lead to long-term gains for the Chinese economy. Plus, the government’s crackdown adds to investor confidence across the region.

And don’t forget: China’s economy is still humming along nicely. And earnings remain strong despite signs of moderation. Industrial companies’ profits jumped 24% in March from a year-ago, extending a surge from the first two months of 2017.

Plus, speculation has returned about massive infrastructure projects.

The “One Belt, One Road” initiative champions railways, ports, roads, dams, pipelines and industrial corridors across dozens of countries in Asia, Europe and Africa. And the program will spur a ton of economic growth for China and the region.

The initiative also offers China a way to boost its stagnating economy, push development into its western regions, open new markets, strengthen links with resource-rich countries and extend China’s political clout.

The bottom line: China and most of the Asian region are still among the brightest economic hotspots on the planet. And they’ll remain so for many years to come, if not decades.

So, how do you play the Chinese stock market in the months ahead?

My team and I are monitoring the markets in China and the rest of Asia very closely. And once the dust settles from this short-term turbulence, we will be ready to pick up a boatload of high-quality Chinese stocks on the cheap.

Right now, our radar has been pinging natural-resource companies like China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (SNP) or Sinopec Shanghai Petrochemical Co. Ltd. (SHI) and technology companies like Changyou.com Ltd. (CYOU) or YY Inc. (YY).

But just like in all investing, timing is everything! So remain patient and make sure you use the right signals at the right time.

Good investing,

Mike Burnick

GUALFIN, ARGENTINA – As longtime Diary sufferers know, we don’t do real stock analysis.

GUALFIN, ARGENTINA – As longtime Diary sufferers know, we don’t do real stock analysis.

We just look for Really Simple Patterns (RSPs).

The simplest we’ve discovered so far: If a market is cheap now, it will probably be less cheap before you get around to investing in it. If it is very expensive, it will probably be less expensive before you get out.

Simple Strategy

This RSP came to mind when Bonner & Partners analyst Chris Mayer, who advises us on our family portfolio, reminded us how much money we made on his latest recommendation.

For our family account, we keep one portfolio made up of country stock market ETFs. We select the countries based on this RSP: We look for the cheapest ones.

As recently as March 30, Chris advised us to put money into five cheap country stock market ETFs. And yesterday, imagining our delight, he sent us the following email update:

Amazing, it’s such a simple a strategy and yet works so well…

So far (since March 30), you are up almost 10% in Turkey, almost 9% in Spain, 8% in Italy, and 5% in South Korea. The only downer is China, down 1%.

Overall, you’re up over 6%… since March.

The only trouble is… we never got ourselves together to make the investment. And on April 15, we suddenly needed the money we had set aside for it to pay the IRS.

Trade of the Decade

But let’s look at another trade, our Trade of the Decade.

This had nothing to do with careful analysis, study, or insight. Just another RSP: Markets that go down for a long time have a good chance of going back up over the next 10 years.

At the debut of the 21st century, we had no trouble identifying a promising setup. Gold had been going down, more or less, for nearly two decades. U.S. stocks had been going up.

So our Trade of the Decade was simple: Sell stocks, buy gold.

It turned out that both sides went our way. Between 2000 and 2010, gold rose about 143%, making it the best-performing major asset class of the decade. And the S&P 500 fell about 25%.

Our next Trade of the Decade was not so simple.

By 2010, gold was no longer a bargain. And U.S. stocks had been beaten down by the 2008 crisis. There was little to be gained by squeezing that orange any further, we reasoned.

What then?

Goofy Program

By the second decade of the 21st century, Japanese stock prices had been falling for 20 years.

Japanese government bond prices, on the other hand, had gone nowhere but up. Why not bet on a reversal?

And so we did in our new Trade of the Decade: Sell Japanese bonds, buy Japanese stocks.

This was based on two other RSPs: (1) Markets that go down a lot tend to go up a lot later, and (2) over time, governments will always destroy the value of their paper currencies.

How has it done so far?

Well, before we get to that, we would like to thank the Japanese government – or, more specifically, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) – for this result.

The Japanese feds have worked tirelessly to boost prices on their stock exchange and send investors fleeing from their bond market.

Why?

It’s just part of their goofy program that is supposed to improve the economy. If they can get the rate of inflation up, they will devalue the yen and make Japanese exports more competitive.

This, in turn, will improve exporters’ sales… leading them to buy more, hire more, and stay in line behind the ruling party.

Claptrap Policies

Accordingly, the familiar claptrap policies were brought on stage.

Shinzō Abe, the country’s prime minister, explained how more “stimulus” – both fiscal and monetary – would surely light a fire under the economy.

It did not. Instead of falling, the yen rose, leaving the Japanese economy soggier than ever.

It must have been then that Mr. Abe and the BoJ decided to go full retard.

They wouldn’t wait for Japanese companies to sell more products and earn more profits. They would simply buy stocks themselves.

Financial blog Zero Hedge:

A year ago, we noted that The Bank of Japan (BoJ) was a Top 10 holder in 90% of Japanese stocks. In December, we showed that BoJ was the biggest buyer of Japanese stocks in 2016. And now, as The FT [the Financial Times] reports, the real “whale” of the Japanese markets is stepping up its buying (up over 70% YoY [year over year]), entering the market on down days more than half the time in the last four years.

Since the end of 2010, The FT notes that the BoJ has been buying exchange traded funds (ETFs) as part of its quantitative and qualitative easing programme. The biggest action began last July, when its annual acquisition target was doubled to ¥6 tn [$8.7 billion].

Since then, the whale designation has seemed pretty obvious: the central bank swallows a minimum of ¥1.2 bn [$10.5 million] of ETFs every single trading day (tailored to support stocks that further “Abenomics” policies), and lumbers in with buying bursts of ¥72 bn [$632.5 million] roughly once every three sessions.

Since the Bank of Japan began this program, investment bank Nomura estimates that it has boosted the Nikkei 225 Index – Japan’s equivalent of the S&P 500 – some 1,400 points.

Thank you very much.

So how are we doing?

Since the start of 2010, the Japanese stock market is up about 33% in U.S. dollar terms… and about three times as much for yen-based investors. As for Japanese government bonds, they have not cooperated.

Try as he may, Shinzō Abe has still not been able to destroy his nation’s currency or degrade its credit.

But we will not despair. The Trade of the Decade still has three years to run. And Mr. Abe is still trying!

Regards,

Bill

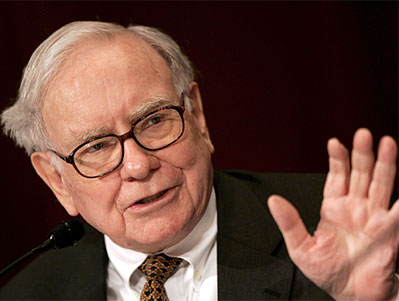

He’s the best investor in the world.

He’s the best investor in the world.

I know that may seem like just an opinion. But is it really an opinion given the remarkable — and unrivaled — track record of the Omaha of Oracle … the one-and-only Warren Buffett?

Now, I do have a few issues with Mr. Buffett. Some are with his politics and others with his investment strategy. Yet I’m also largely in agreement with him, particularly when it comes to his focus on buying good businesses cheap.

I also have intense respect for Buffett’s no-nonsense approach to buying companies he knows and understands … and avoiding those he doesn’t.

This approach has worked for his Berkshire Hathaway (BRK-B) shareholders over the years, and particularly recently.

BRK-B is up more than 100% in the last five years. Yet, Buffett missed out on a lot of big winners over that time.

Amazon.com (AMZN) is one name that comes to my mind, and certainly to his. Yet he’s more than made up for it by his numerous great calls across the markets for many, many years.

Over the weekend, the annual Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting took place, an event sometimes described as the “Woodstock for Capitalists.”

This event always generates a lot of press, and this year’s event was no exception. Here are a few of what I think are the most-interesting takeaways from Berkshire meeting.

In an interview with CNBC host Becky Quick, Buffett made what I thought was a very interesting observation about buying good companies at a high price.

Quick asked Buffett about a statement he made about his See’s Candies acquisition.

Buffett had said previously that if the seller would have tried to get another $5 million from him, he would have said no. And that this would have been a mistake.

“Are you still that cheap?” asked Quick.

Here’s Buffett’s response:

“No, I’m not as cheap. Because that taught me something. I’m still cheap. But not as cheap as I used to be.”

Buffett then added the following words of wisdom to the discussion:

“You can afford to overpay, a bit, for a really fine business depending on your degree of certainty that it’s a really fine business, and is going to stay one for a long, long time. And you can’t make that decision about most businesses.

“I mean, it’s just not given to man to be able to foresee 20 years out on most businesses. On the other hand, if you pay big prices for something, you’re counting on earnings. You’re counting on being right a very high percentage of the time on projections of earnings that go up … “

A few things about this statement intrigued me.

***

First, Buffett acknowledges that it’s sometimes OK to pay (slightly) more for what you think is a good business.

I never like to pay too much for a good business (i.e., a good stock). But if metrics like great free cash flow show the business is really good, it may at times be OK to buy that stock despite a high valuation.

|

Then Buffett acknowledged how difficult it is to prognosticate into the future about any business. He said this ability is “just not given to man.”

This acknowledgement — that the future is supremely unknowable — is something I don’t think Buffett gets enough credit for.

People would rather ascribe to him some kind of investing superpowers. They would be better-served to instead acknowledge the consistent, principled and humility-infused approach he comes to the market with each day.

Finally, Buffett warns that if you pay too big a price for something, you are always going to need bigger and bigger earnings to keep those prices up.

Well, that’s a difficult thing to do for any business, no matter how sound it may be.

It’s also tough to do in the aggregate.

So, when I think of the post-election rally … and how it’s been built largely on hope of pro-growth policies being passed in Washington … I get worried.

At some point, real earnings and real economic growth are going to have to match those lofty expectations. Otherwise, stocks won’t be able to trade materially higher from here.

Knowledge of that outcome is not given to man, either …

But my suspicion is that disappointment on this front is a lot likelier than the flipside of that coin.

***

The markets seemingly breathed a sigh of relief after Emmanuel Macron won the French presidential election by a 20%-plus margin. The euro briefly climbed to a six-month high vs. the greenback before traders took some profits off the table.

Here in the U.S., stocks mostly clung to the flat line during Monday’s session. Meanwhile, volatility fell 8% to a 24-year low and gold came off its worst weekly decline since October. Bullion gained 0.2 points to end at $1,227 per troy ounce.

• OPEC might extend its production cuts into 2018: The cuts, set to expire next month, will be reviewed in Vienna on May 25. WTI crude ended the day 0.5% higher at $46.43 per barrel.

• ‘Woodstock’ moves from Omaha to Manhattan: Hedge fund legends like Bill Ackman, Stanley Druckenmiller, David Einhorn and Jeffrey Gundlach are revealing some of their major trades at the Ira Sohn Investment Conference today. After Ackman talked about his stake in real estate company Howard Hughes (HHC), shares spiked almost 4%.

• Record-breaking day for Apple (AAPL): The company’s market cap hit $800 billion for the first time. It was at $775 billion in February 2015. Shares gained 2.7% to close at $153 today.

• Coach (COH) bagged Kate Spade (KATE) for $2.4B: The deal, which sent COH shares up nearly 5% and KATE up 8.3%, sparked speculation that Jimmy Choo may be a shoe-in as Coach’s next takeover target. Coach might also add Burberry’s plaid to its luxury-accessory lineup, according to reports.

Good luck and happy investing,

Brad Hoppmann

Are High Home Prices Turning American Millennials Into the New Serfs?

Are High Home Prices Turning American Millennials Into the New Serfs?

The Complacent Class

The Distortion of Time and Work

Orlando and SIC

“Being young and having no job remains stubbornly common. Wages for young people fortunate enough to get a job have gone down. Inflation-adjusted wages for young high school graduates were 11 percent higher in 2000 than they were more than a decade later, and inflation-adjusted wages of young college graduates (four years only) have fallen by more than 5 percent. Unemployment rates for young college graduates have been running for years now in the neighborhood of 10 percent and underemployment rates near 20 percent. The sorry truth is that a lot of young people are facing diminished job opportunities, even several years after the formal end of the recession in 2009, when the economy began to once again expand after a historic contraction.”

– Tyler Cowen, Average Is Over, 2013

“There are two ways to conquer and enslave a nation. One is by the sword. The other is by debt.”

– John Adams, 1826

“The problem with fiat money is that it rewards the minority that can handle money, but fools the generation that has worked and saved money.”

– Adam Smith

“Debt drains away vital resources from economic growth. Fighting a debt crisis with more debt is doomed to failure, yet that is not only what global central banks did during the crisis but long after markets stabilized (though the crisis never truly ended, just slowed). This was an epic policy failure that continues today.”

– Michael Lewitt, The Credit Strategist

I fully intended to end my series on “Angst in America” last week, moving on to portfolio construction and what I call the Great Reset. But as I did my regular reading and research this week and reflected on it, I realized there was one piece missing from this series. That is a discussion of the angst that the Millennial generation and generations that follow are facing. And this is not just a US problem; it’s global.

As most of you know, I am working on a book called The Age of Transformation. It’s about how the world may look in 20 years. I hope to finish it before 2037! Things keep changing, and at an accelerating pace. One of the most important chapters – and the most difficult to write – is on the future of work. I entered into this project with a techno-optimist perspective. New technology, while destroying old jobs, would create new jobs and opportunities.

A clear example of this is the use of drone technology by the military. It requires about 100 people to prep and launch and maintain an F-16 for a single mission. Keeping an unmanned predator drone in the air for 24 hours requires about 168 workers laboring in the background. A larger drone, such as a Global Hawk surveillance craft, needs about 300 people working in the background to make the mission feasible. One of the real problems for the Air Force is recruiting enough people with the savvy to fill these needs.

But here’s the problem. The world is dividing into people who can manipulate information using computers and those who can’t. The differential in wages between these groups is significant. Thomas Piketty, the socialist French economist who wrote the book Capital in the Twenty-First Century (an enormously flawed work), does make the valid point that the gap between the poor and the rich, and between the middle class and the rich, is widening. Very little dispute about that. (He really didn’t need to cook his economic data to demonstrate his case.) Enter Tyler Cowen, whose book Average Is Over I have been reading and mulling over for some time now. Cowen says the ability to mix technological knowledge with the ability to solve real-world problems is the key to being a big earners in a polarized labor market. The productive worker and the smart machine are becoming ever more complementary. As one reviewer said, “Only those who can learn to think like smart machines or at least enough to understand their operation will get success. Individuals who work with genius machines will need to retrain and learn new systems constantly.”

So there are reasons to be concerned about my techno-optimist view. The new jobs will only be available to those who have real aptitude and real training. You may be highly educated, with a PhD in music or literature or even in economics, but the demand for your skills is nowhere near as high as the demand for a super nerd who dropped out of college and can sling code in his sleep. If, on the other hand, you understand how to generate leads and new subscribers using Facebook – something that really doesn’t require a computer science degree but does demand a highly focused and integrated understanding of web technology and marketing – you’ll find people lined up to throw money at you.

(Now that I mention it, if you are such a person, send us your résumé. We haven’t cracked the code to achieve sustainable marketing profitability through Facebook, and there are a significant number of others in our industry who are facing the same issue. We are getting better at it. But it seems like every time we think we have it figured out, Facebook and Google and the rest of them change their algorithms, and we have to start all over again, which means that the young geniuses we hire have to figure it all out again. And the cycle seems to be getting faster.)

What triggered my thinking on these topics this week was a lengthy piece by Marc Faber. Faber looks at a question being asked by a couple of other writers: Are the Millennials turning into the new serfs? With the massive amount of debt they have accumulated, not just in student loans (which are horrendous), but also in auto loans and other types of debt as well. With their income-generating potential down from that of previous generations, this generation may be in trouble (a problem I will be writing about in my book on the future of work). Now, Marc writes longer pieces, and this letter was 38 pages; but he gave me permission to pull out a few paragraphs here and there and stitch them together into a shorter piece, which we’ll turn to next. Then I’ll add some final comments on the future of work for Millennials.

Are High Home Prices Turning American Millennials Into the New Serfs?

By Marc Faber

(Excerpted from the Gloom, Boom & Doom Report, March 2017)

Writing for http://www.dailybeast.com (February 4, 2017), Joel Kotkin opines under the title “The High Cost of a Home Is Turning American Millennials Into the New Serfs” that

American greatness was long premised on the common assumption was that each generation would do better than previous one. That is being undermined for the emerging millennial generation.

The problems facing millennials include an economy where job growth has been largely in service and part-time employment, producing lower incomes; the Census bureau estimates they earn, even with a full-time job, $2,000 less in real dollars than the same age group made in 1980. More millennials, notes a recent White House report, face far longer period of unemployment and suffer low rates of labor participation.”

More than 20 percent of people 18 to 34 live in poverty, up from 14 percent in 1980. They are also saddled with ever more college debt, with around half of students borrowing for their education during the 2013–14 school year, up from around 30 percent in the mid-1990s.

All this at a time when the return on education seem to be dropping: A millennial with both a college degree and college debt, according to a recent analysis of Federal Reserve data, earns about the same as a boomer without a degree did at the same age.

This is a serious problem. According to a study by the Huffington Post (February 3, 2016), “President Barack Obama has said that a college degree ‘has never been more valuable.’ But if you borrow to finance your degree, the immediate returns are the lowest they’ve been in at least a generation, new data show.

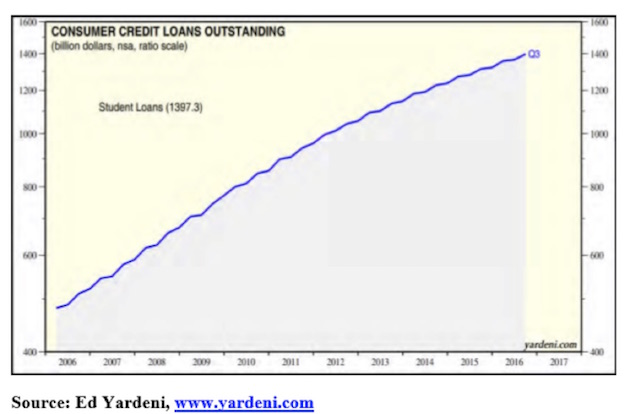

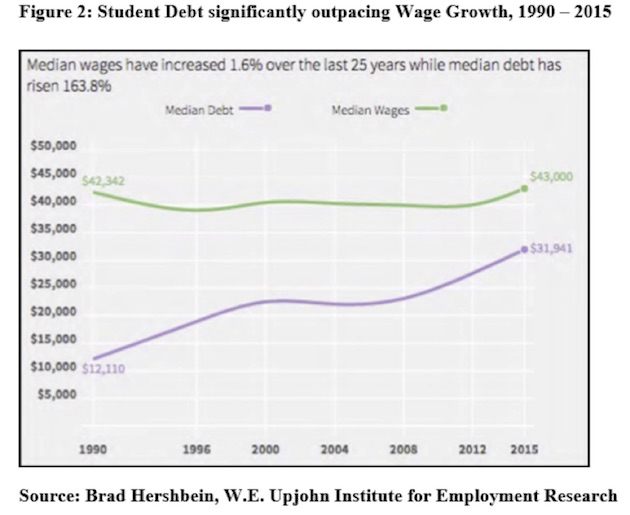

Wages for the typical recent college graduate working full time have risen just 1.6 percent over the last 25 years, after adjusting for inflation, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.” At the same time, student debt burdens for the typical bachelor’s degree recipient who borrowed for college have increased about 163.8 percent (see Figure 2).

The Huffington Post analysis further states that, “In 1990, the typical college student graduated with debt equivalent to 28.6 percent of her annual earnings. By 2015, that number had shot up to 74.3 percent, data show.” Moreover,

Student debt at graduation for the typical bachelor’s degree recipient could exceed annual wages by 2023, if both figures continue to grow at the same annual rate of the last 25 years. Roughly 42 million Americans collectively owe more than $1.3 trillion on their student loans, federal data show. Total student debt has doubled during the Obama administration. More than 90 percent of student debt is either owned or guaranteed by the U.S. Department of Education. Stagnant wages and the jump in student debt levels has prompted growing concern among government policymakers and financial industry executives that student debt risks slowing U.S. economic growth as households reduce their spending to make their student loan payments. About 7 of every 10 college graduates now borrows to pay for higher education, up from about half in the 1990s, data show. [emphasis added]

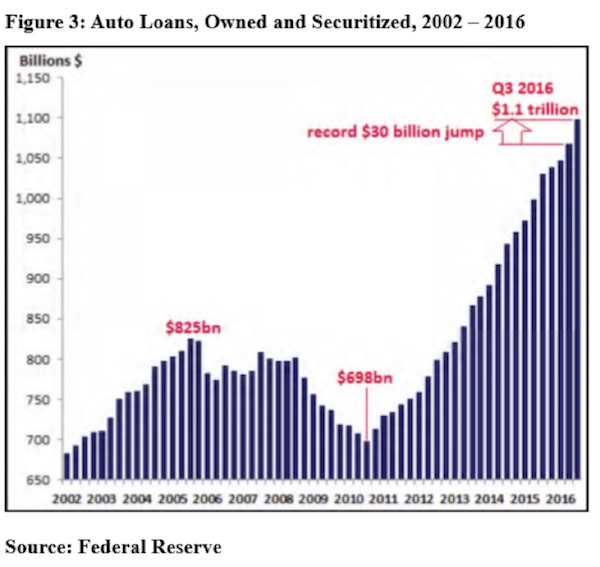

I should mention that not only “student debt risks slowing U.S. economic growth as households reduce their spending to make their student loan payments.” The same also applies to auto loans, which have almost doubled since 2010 and other credit as well. Never mind what the neo-Keynesians say, excessive debts in a society reduce its growth potential as we have seen since the late 1990s and as Mr. Trump will likely also realize.

But back to the dailybeast.com article (“The High Cost of a Home Is Turning American Millennials Into the New Serfs”), which further notes that,

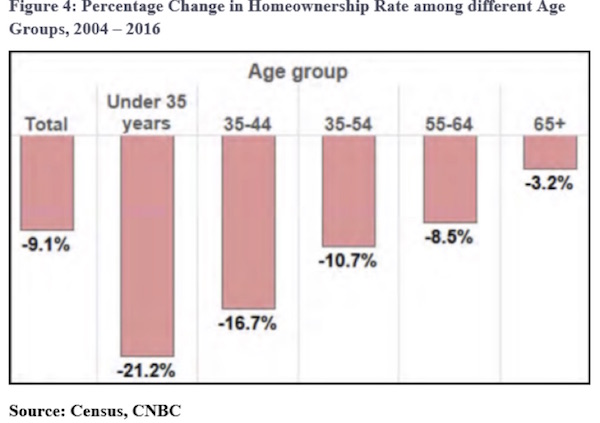

Downward mobility, for now at least, is increasingly rife. Stanford economist Raj Chatty finds that someone born in 1940 had a 92 percent chance of earning more than their parents; a boomer born in 1950 had a 79 percent chance of earning more than their parents. Those born in 1980, in contrast, have just a 46 percent chance. [See also Figure 9 of last month’s report.] Since 2004, homeownership rate for people under 35 have dropped by 21 percent, easily outpacing the 15 percent fall among those 35 to 44; the boomers’ rate remained largely unchanged. [See Figure 4.]

Dailybeast.com emphasizes that,

In some markets, high rents and weak millennial incomes make it all but impossible to raise a down payment. According to Zillow, for workers between 22 and 34, rent costs now claim upward of 45 percent of income in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Miami, compared to less than 30 percent of income in metropolitan areas like Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston. The costs of purchasing a house are even more lopsided: In Los Angeles and the Bay Area, a monthly mortgage takes, on average, close to 40 percent of income, compared to 15 percent nationally.

I need to clarify the point that, “for workers between 22 and 34, rent costs now claim upward of 45 percent of income in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Miami.” This is certainly true, but in New York, the median rent-to-income ratio or the share of total household income necessary to pay median asking rent is frequently above 50% (see Figure 5). So when Joel Kotkin writing for dailybeast.com says that,

Like medieval serfs in pre-industrial Europe, America’s new generation, particularly in its alpha cities, seems increasingly destined to spend their lives paying off their overlords, and having little to show for it. No wonder that rather than strike out on their own, many millennials are simply failing to launch, with record numbers hunkering down in their parents’ homes. Since 2000, the numbers of people aged 18 to 34 living at home has shot up by over 5 million

– he is spot on. Since the homeownership rate peaked out in the US in late 2004, the biggest drop has come from households under the age of 35.

Kotkin then explains that a common theme in the mainstream media is that millennials don’t want to buy homes. The new generation, it is said is part of “an evolution of consciousness” – whatever that means is beside the point. Other observers claim that the young have embraced “the sharing economy,” so that owning a home is simply not to their taste. I have also seen financial advisors recommending young people not to buy a home because home prices have increased far less than an investment in equities over time despite the fact that until recently, gains in US housing were matching those of the equity markets toe to toe since 2011 bottom in US house prices.

However, according to Kotkin,

[It] is “not a lifestyle choice but economics – high prices and low incomes – – that are keeping millennials from buying homes. In survey after survey the clear majority of millennials – roughly 80%, including the vast majority of renters – express interest in acquiring a home of their own. Nor are they allergic, as many suggest, to the idea of raising a family, albeit often at a later age, long a major motivation for home ownership. Roughly 80% of millennials say they plan to get married, and most of them are planning to have children. Overall, more than 80 percent of millennials already live in suburbs and exurbs, and they are, if anything, moving away from the dense, expensive cities. Since 2010 millennial population trends rank New York, Chicago, Washington, and Portland in the bottom half of major metropolitan areas while the young head out to less expensive, highly suburbanized areas such as Orlando, Austin, and San Antonio.

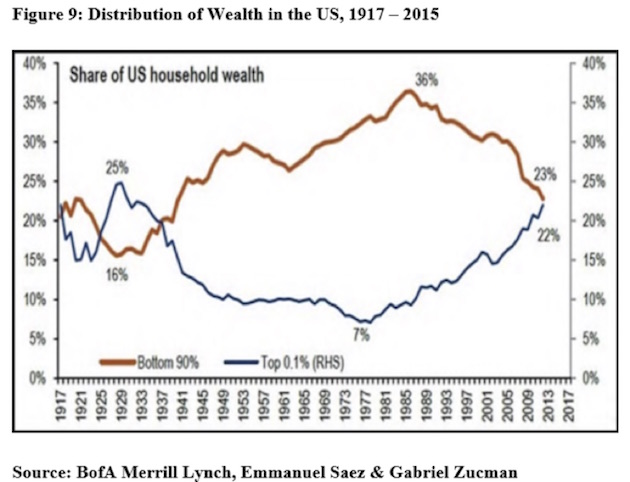

… In this respect what is interesting is that whereas Mr. Trump was elected (partly) because he promised to improve the condition of the American worker, since his election the 0.1% have gained the most as the stock market capitalization has increased by over $2 trillion. Therefore, by now the wealth of the top 0.1% should exceed the wealth of the bottom 90% for the first time since 1941. Remarkably, the recent pronouncements by Trump and coterie suggest that they equate the stock market strength with a strong economy as well….

Surely the millennials grew up in a more affluent and more “take it easy” environment than the boomers who were brought up by a generation of parents that had experienced the hardship of depression years and the horrors of the Second World War. The millennials’ parents were mostly frugal, debt averse because of the experience of the depression where indebted households lost everything (just like in 2008/2009), and they had a high saving rate.

Therefore, compared to the boomers it is only natural and completely understandable that the millennials’ drive for achievement and thriftiness are inferior to the one that their parents had. But can the relative decline of the financial condition of the millennials be satisfactorily explained by their less entrepreneurial spirit?

In “Dreaming Small – Is America Losing the Restlessness of Spirit That Once Powered Its Economy?” Edward Luce reviews Tyler Cowen’s book The Complacent Class: The Self-Defeating Quest for the American Dream. (See Financial Times, February, 17, 2017.)

Luce does not only write perfect English but also describes cynically how today’s society functions by quoting Cowen extensively. He writes:

In his new book, The Complacent Class, Cowen expands the scope of the argument to sociology. He believes America’s restlessness of spirit is giving way to a safety-first society. Instead of pushing on to the next frontier, Americans are busy gentrifying the neighbourhood. They are also making it harder for others to move in.

We used to suffer from the Nimby syndrome – ‘not in my backyard’. Now we have graduated to Banana – ‘build absolutely nothing anywhere near anything’, says Cowen. Public life is stymied by Cave (‘citizens against virtually everything’) in which politicians fall back on Nimey (‘not in my election year’). Politics has reduced itself to a theatre of symbolic gestures in which pressing issues are left unaddressed. Behind all the electoral volatility lies stasis. Perhaps that is just as well. During the heyday of non-conformism in the 1960s, almost two-thirds of America’s federal budget was discretionary. Now almost 80 per cent of it is locked up. Donald Trump is unlikely to change that.

As a matter of fact, it is actually much worse. According to figures provided by http://www.usdebtclock.org, Tom Mclellan calculated that six mandatory “spending items already account for more than all of the tax revenue coming in, and that is before you pay a single federal civilian employee’s salary, before any discretionary spending, before any research grants, any foreign aid, any NASA rockets, any state dinners, any toxic waste cleanup, any wall-building, any highway or airport improvements, etc.” I shall return to the budget problem further below.

For now, back to Edward Luce, who explains that

Cowen views Trump as the ultimate expression of a country that wants to turn the clock back. America’s 45th president is an authoritarian nostalgist who won by promising to shield voters from the forces of change. People were voting for a return to the certainties of the 1950s. ‘What I find striking about contemporary America is how much we are slowing things down, how much we are digging ourselves in, and how much we are investing in stability,’ writes Cowen. Though they heavily rejected Trump, this is just as true of America’s creative classes, says Cowen. America’s big metropolises and college towns may be the most liberal enclaves in the country. But they are also the most unequal. Just as zoning restrictions keep out low-income housing developments, so the world of social media allows us to screen out opinions we do not like.

We use dating algorithms to sift our romantic field in the same way employers scour social media to screen out misfits. The internet gives us the illusion of speed and change. In reality it is narrowing the scope for serendipity. America is turning into a society of matchers and sorters. ‘We are using the acceleration of information transmission to decelerate changes in our physical world,’ says Cowen.

The spirit of risk-aversion is also infecting corporate America. The once lavish budgets companies devoted to research and development are now spent on legal compliance and human resources. Corporate income is no longer invested in future growth. Earnings are instead returned to shareholders through dividends or share buybacks. The rate of US start-ups has also slowed to a historic low. In the 1980s, by one estimate, such businesses employed 12-13 per cent of Americans. That has now fallen to 7-8 per cent. ‘The complacent class itself has ceased to believe in the regenerative properties of the world we all inhabit,’ says Cowen. America is ageing and older societies take fewer risks. They also try to hold on to what they have. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the millennial generation is the least entrepreneurial of all, in Cowan’s view. They are ‘most committed ideological carriers’ of the new spirit of complacency. [emphasis added]

Lately, the spirit of complacency seems to have infected the financial sector as well. Moreover, the “spirit of complacency,” “the spirit of risk-aversion,” and “how much we are investing in stability” is not endemic or unique to the US. It is probably far worse in Europe and in Japan. But these conditions are nothing new. Edward Gibbon wrote that risk aversion was already a problem among the Athenians: “In the end more than they wanted freedom, they wanted security. When the Athenians finally wanted not to give to society but for society to give to them, when the freedom they wished for was freedom from responsibility, then Athens ceased to be free.”

To be fair to the millennials (and most of the ones I know personally are very intelligent, hard-working, entrepreneurial, and responsible) government policies and the propaganda machine of the mainstream media encourages their false sense of security as gospel “truth” is largely absent from the government and the mainstream media’s vocabulary. The government lies about its true fiscal position and about the “true” rate of cost of living increases while the FED plays its part by communicating to the public that any economic problem can be overcome by money printing and more money printing.

I have discussed the Chapwood Index in earlier reports. It is published every quarter by monitoring 500 items which households most frequently use across 50 cities. According to the Chapwood Index the real cost of living rose by a startling 9.6% in 2016 – very close to John William’s rate and has averaged 10% a year over the last five years. At the same time, the academic economic charlatans do not exactly encourage “thrift” by advocating negative interest rates and even more negative rates still if the first set of negative rates fails to revive the economy.

The generation of millennials born after 1995 have been shaped by the debt-growth induced 1990s’ period of boom and prosperity, which was driven largely by rising asset prices. The good side of generation Z is that they are not interested in wars (they seldom ever belong to warmongers) and care little about politics. Unfortunately, they have only a scant knowledge of the meaning of “freedom” and “personal responsibility”.

However, they are concerned about political correctness, about having the latest-model iPhone and the number of likes their photos receive and how many followers they have on Facebook. But most of all, they are concerned about extracting as much as possible from the government in the form of subsidies and other kinds of benefits. It is a generation that avoids hard work (such as on the factory floor), and is content to work part-time in bars and restaurants, and to live a carefree existence. It is also the generation whose major contribution to civilization may be the invention of “retirement before working.”

Needless to say, this concept of retirement before working has been fostered and encouraged by governments, which, with their generous transfer payments, make it more economical for some people not to work, and to collect all kinds of tax-free benefits, than to have a low-paying occupation and pay taxes.

Edward Luce concludes his review of Tyler Cowen’s The Complacent Class by noting that Cowen believes,

[S]ociety may be returning to a cyclical view of history in which human progress is no longer something we will automatically expect. We may take a generation or so to adjust to the new reality. Millennials are already leading the way. They are the least angry group of Americans politically, perhaps because they have grown up with more realistic expectations than their elders. Bleak though this sounds, millennial passivity is in some ways reassuring, Cowen believes. The anger that carried Trump to the White House may be but a stage on the path to society’s acceptance of lower growth.

In most other ways, Cowen’s thesis is deeply troubling. Democracy requires growth to survive. It must also give space to society’s eccentrics and misfits. When Alexis de Tocqueville warned about the tyranny of the majority, it was not kingly despotism that he feared but conformism. America would turn into a place where people “wear themselves out in trivial, lonely, futile activity”, the Frenchman predicted. This modern tyranny would “degrade men rather than torment them”. Cowen does a marvelous job of turning his Tocquevillian eye to today’s America. His book is captivating precisely because it roves beyond the confines of his discipline. In Cowen’s world, the future is not what it used to be. Let us hope he is wrong. The less complacent we are, the likelier we are to disprove him.

The Distortion of Time and Work

(Final thoughts from John)

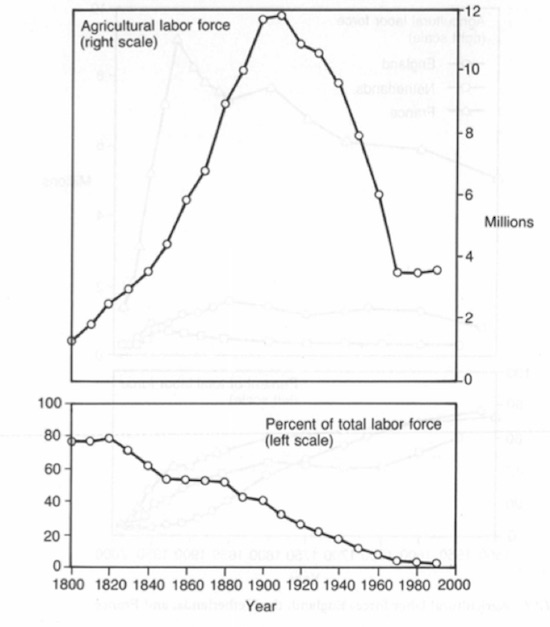

What both Cowen and Faber are talking about is a trend that I believe is going to accelerate. In the last few centuries we have seen an enormous displacement of the workforce, particularly in agriculture as the Industrial Revolution took hold and triumphed. We went from 80% of the country working on farms in 1820 to less than 2% today.

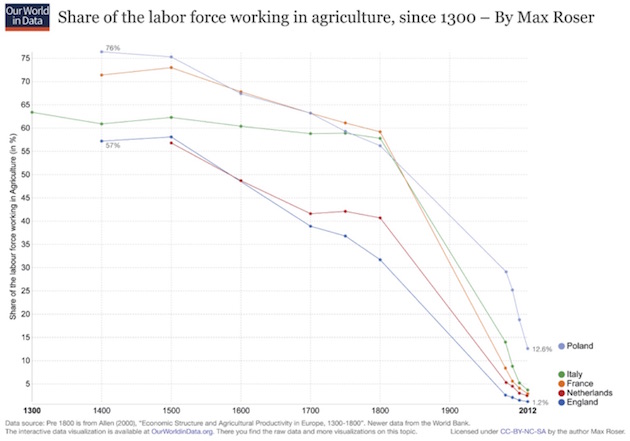

This is not just a US phenomenon. I found this cool chart that shows the share of the labor force working in agriculture in the major European countries, going back to 1300. England is down to 1.2%.

But those massive changes played out over 20 or so generations. Now, we are witnessing wholesale change in numerous industries in less than half a generation. In a recent TED Talk, Elon Musk showed off a mysterious semi-tractor capable of hauling extraordinarily large loads using electrical power. They have had the prototype for maybe a year. In less than five years, companies will be able to purchase a completely electrically powered self-driving truck. I am sure the first trucks will have a place for the driver to sit, but it won’t be long before the need for drivers will disappear. Ditto for taxis and other local transportation. Six million taxi, Uber, and truck drivers will find themselves out of a job. In 10 years. That is not much time to adjust your career path.

We have an economy burdened by debt, coupled with a workforce growing slowly. Further, enhanced productivity (at least the way we measure it now) in the service industries will also mean that fewer people have jobs – not exactly the outcome a labor economist wants to see.

The picture is not entirely gloom and doom. There will be a large cultural shift in the way work and income are allocated. But that is going to require society to go through wrenching changes, because our expectation seems to be that we can somehow get back to the nirvana of the ’50s through the ’90s. That is just not going to happen. And we’re going to have to adjust far more quickly than our great-great-grandparents and their children did in going from the farm to the factory to the office.

So, yes, much angst for the Millennial and younger generations. Helpfully, they seem to be more realistic about their future than my generation was. But they are not as entrepreneurial and risk-taking as previous generations were, and those are the qualities required to grow an economy.

Let’s finish with a set of quotes from Tyler Cowen’s book Average Is Over.

Being young and having no job remains stubbornly common. Wages for young people fortunate enough to get a job have gone down. Inflation-adjusted wages for young high school graduates were 11 percent higher in 2000 than they were more than a decade later, and inflation-adjusted wages of young college graduates (four years only) have fallen by more than 5 percent. Unemployment rates for young college graduates have been running for years now in the neighborhood of 10 percent and underemployment rates near 20 percent. The sorry truth is that a lot of young people are facing diminished job opportunities, even several years after the formal end of the recession in 2009, when the economy began to once again expand after a historic contraction.

At the same time, the very top earners, who often have advanced postsecondary degrees, are earning much more. Average is over is the catchphrase of our age, and it is likely to apply all the more to our future. This maxim will apply to the quality of your job, to your earnings, to where you live, to your education and to the education of your children, and maybe even to your most intimate relationships. Marriages, families, businesses, countries, cities, and regions all will see a greater split in material outcomes; namely, they will either rise to the top in terms of quality or make do with unimpressive results.

These trends stem from some fairly basic and hard-to-reverse forces: the increasing productivity of intelligent machines, economic globalization, and the split of modern economies into both very stagnant sectors and some very dynamic sectors. Consider the iPhone. The iPhone is made on a global scale, and it blends computers, the internet, communications, and artificial intelligence in one blockbuster, game-changing innovation. It reflects so many of the things that our contemporary world is good at, indeed great at. Today’s iPhone would have been the most powerful computer in the world as recently as 1985. Yet to cite two contrasting sectors, typical air travel doesn’t go faster than it did in 1970, and it is not clear our K–12 educational system has much improved.

This imbalance in technological growth will have some surprising implications. For instance, workers more and more will come to be classified into two categories. The key questions will be: Are you good at working with intelligent machines or not? Are your skills a complement to the skills of the computer, or is the computer doing better without you? Worst of all, are you competing against the computer? Are computers helping people in China and India compete against you?

If you and your skills are a complement to the computer, your wage and labor market prospects are likely to be cheery. If your skills do not complement the computer, you may want to address that mismatch. Ever more people are starting to fall on one side of the divide or the other. That’s why average is over. This insight clarifies many key issues, such as how we should reform our education; where new jobs will come from and why (some) wages might start rising again; which regions will see skyrocketing real estate prices and which will empty out; why some companies will get smarter and smarter, while others just try to ship product out the door; which human beings will earn a lot more and which workers will move to low-rent areas to make ends meet; and how shopping, dating, and meeting negotiations will all change.

My next trip will be to the Strategic Investment Conference, May 22–25 in Orlando. On the 26th, Shane and I fly up to Washington DC to be with Neil Howe and bride Gisela at their wedding. And in late June Shane and I will fly to St. Thomas for a week of vacation.

As I mentioned last week, the list of reasons why you should attend the Strategic Investment Conference keeps growing. My friend Marc Faber has now agreed to speak and serve on a few panels. The last day will be a panel composed of George Friedman, Mark Yusko, Neil Howe, and Matt Ridley. George needs no introduction to my readers. Mark Yusko is a renowned investor who is the founder and chief investment officer of Morgan Creek Capital Management. Neil Howe wrote The Fourth Turning, which was the driver for Steve Bannon’s documentary, Generation Zero. Neil will be telling us what the next 10 years are likely to hold as we enter the latter half of this Fourth Turning). Matt Ridley is the brilliant Libertarian thinker/philosopher and prolific author who wrote The Rational Optimist and The Evolution of Everything, which I think is one of the best books of the last five years.

I’m going to moderate the panel and engage them in a discussion about how the next 10 years will unfold. I can’t imagine anything more exciting. Well, except the rest of the conference, where Ian Bremmer and Pippa and Harald Malmgren will not only make their own presentations, but also sit down with George Friedman in a no-holds-barred panel on current geopolitics. Lacy Hunt, David Rosenberg, Raoul Pal, Grant Williams, Martin Barnes, some of the most noted cutting-edge biotech scientists, and an energy panel with two billionaires who actually know how to pull oil out of the ground and tap energy from the sun. They are not just investors; they have built their own “mini-empires” from scratch and have an extraordinary view on the future of energy and natural resources. And the list goes on and on and on.

You really do want to figure out how to get Orlando May 22–25, if you haven’t already made arrangements. This is where you can get the information you need to navigate the Great Reset successfully. Make sure your spot is reserved.

Next week I really am going to write about the Great Reset and talk specifically about how I think we need to adjust our core portfolios. But in the meantime, as part of the launch of my new portfolio management company, I will be hosting, on May 17 at my home, a chili and prime dinner for independent brokers and advisers, where we will share with you the specifics of how we are going about changing the way you manage the core of your portfolio. As I keep saying, the key is to diversify trading strategies, not just asset classes. Technology has allowed us to do some marvelous new things, and portfolio diversification that smoothes out the ride is one of them. One of my goals is to be able to help brokers and advisers get their clients through the storms that we all know are coming as the world struggles to figure out how to deal with the massive amounts of debt and government obligations that are building up. Maybe not this year, but at some point there ha s to be a Great Reset, and you need to be able to get your clients through it. If you’re interested in attending to learn more about what we’re doing, drop a note to me at business@mauldinsolutions.com. Give me your name and your firm, and we’ll get back to you ASAP. (You really don’t want to miss my prime and chili. Two quite different dishes, yet both have been perfected.)

And with that I will hit the send button. I have a very full week in front of me, but I am going to take Saturday night off and go see Guardians of the Galaxy, Part Two. I hold that a little escapism every now and then is good for the soul. You have a great week.

Your enjoying being home analyst,

John Mauldin

subscribers@MauldinEconomics.com

How does one construct a portfolio in an era of seemingly ever rising and highly correlated asset prices? Years of asset prices moving higher has changed both retail and institutional investors; it has changed the industry; and, in my humble opinion, those changes spell trouble. The prudent investor might want to take note to be prepared.

I allege that for many, investing is no longer about prudent asset allocation, but about expressing themes. If you like green technology, you tilt your portfolio towards green energy. If you are socially conscious, there’s an ETF for that. I have no problem with anyone alloca ting money to any specific theme. However, has anyone else noticed that it doesn’t matter what theme you allocate money to? Investors are all playing the lottery and guess what: everyone’s a winner!

Now, clearly, that’s an over simplification, as not every industry does well all the time – just ask those who invested in MLPs (master limited partnerships) in pursuit of income from fracking. Let me rephrase: the more of a monkey you have been, i.e. the less you have been thinking, the better you’ve likely performed over the past nine years. “Buying the dips” has been a consistently profitable strategy.

That has created numerous oddities:

- Take the investor who diversifies, rebalancing part of a portfolio to near zero-income generating fixed income. Advisors pursing such strategies have seen their clients take money away, as they are not willing to pay a management fee for essentially holding cash.

The problem: cash is discarded even if it may be a prudent investment choice.

- Take the investor who diversifies, rebalancing part of a portfolio to alternative income streams.

The problem: Anything that generates an income in a zero-income environment is, almost by definition, risky. That is, both stock and fixed income securities in such a portfolio are so-called risk assets, i.e. I believe they are likely to move in tandem, not providing desirable diversification in a downturn.

- Take the prudent investment advisor who has allocated part of a portfolio to true alternatives, such as long/short equities or long/short currencies. While providing diversification, such portfolios have likely underperformed during the relentless rise of equities. Worse, when the markets have had a hiccup, such as in early 2016, many of those portfolios still lost money, as the volatility of risk assets overwhelmed the cushion provided by the alternatives. Read: clients have been abandoning advisors, lured by competitors showing how great their performance has been, investing 100% in equities since the spring of 2009.

The problem: Those solicitations conveniently skip the inconvenient fact that their clients lost huge in 2008.

- Take the investor who wants to participate in the upside, but be protected on the downside.

The problem: they spend a small fortune buying insurance, even when they might be better off just holding a cash buffer (again, advisors don’t hold cash, as clients would withdraw that cash at some point).

- If many want to buy insurance, someone needs to write insurance. The one thing more profitable than buying stocks may well have been to write insurance. Funds that “sell volatility”, amongst others, have been amongst the best performers in the first quarter. Mind you, we do not recommend you touch any such product with a broomstick unless you know exactly what you are doing and able to stomach some serious losses. The theory behind many of these funds is that you collect what amounts to an insurance premium when volatility is low; the periods when you have to pay up are short and intense, but those setbacks are ultimately temporary.

The problem: Earlier this year, one such fund was in the news for substantial losses, not because volatility spiked, but because portfolio management got cornered when they tried to roll derivative contracts. Let’s just say: something that looks too good to be true, may well be. Interesting things may well happen (read “contagion”) if and when these positions unwind.

- Active management is dead. Long live passive investing. Never mind that anything but an index fund on the broad market is an active investment choice. The point being that you don’t want to pay some smart cookie to try to beat the market. That’s because those so-called experts were wrong in 2008 (and many times since). What can they possibly know? Besides, your favorite green tech investment fund is doing just fine, thank you very much.

The problem: Cautions provided by active managers help one frame possible risk scenarios. Managing risk is important, even if many risks never materialize.

- Active managers are leaving the industry. Who needs anyone skilled in navigating rough waters when you have robots providing liquidity?

The problem: it may be helpful to have a captain on board when the auto-pilot fails.

- Brokers are increasingly hand-holding relationship people, with portfolio allocation decisions being made by a small group creating model portfolios. After all, why risk your job trying to go out on a limb for your client?

The problem: there’s nothing wrong per se with this trend, except that it increasingly concentrates investment decisions for huge amounts of money into very few people. We hope they are smart. Importantly, we hope investors understand who makes the investment decisions and what the conflicts are. Let’s just say: when something goes wrong, class action lawyers will have their day in court.

- An increasing number of investors are skipping advisers altogether. After all, why not cut out the middle man if they don’t know any better than you do?

The problem: there’s no problem with do-it-yourself investing except, just as professionals, investors owe it to themselves to make prudent investment decisions. We think that many individual investors do a better job than some professional investors these days in allocating their money. That said, that’s a very low bar.

- If you have enough money, you allocate some money to venture capital. At least you have something to talk about at cocktail parties. It might help if you knew what your venture capital fund invested in, but let’s not get distracted by details.

The problem: no problem if you can afford it. May I make the suggestion, though, that you first try to understand your overall portfolio, before you dabble in illiquid investments?

What could possibly go wrong?

Quite simply, markets do go down, not just up. In my view there is an increased risk of a flash crash in an environment where we are ever more dependent on automated liquidity providers that might withdraw liquidity the instant there’s an anomaly in the market (read: if you place a market order to sell a security, don’t complain if the market price is dramatically below the most recent trade on an exchange).

While regulators may be all over flash crashes and possibly bail you out by canceling your order, a more pronounced decline is something you might want to prepare for as well. We hear pundits proclaim that we cannot have a bear market unless there’s a recession. There are couple of problems with that:

- First, it’s not true. There was no recession during the October 1987 crash.

- Second, we often don’t know whether there’s a recession until we are well into it; there have been instances when we didn’t know there was a recession until it was over.

- Third, we’ll only know we are in a “bear market” when the market is down 20%. That’s kind of late to prepare for a bear market. Except, of course, if the market tumbles much more than that, such as the Nasdaq after 2000; or the S&P 500 in 2008.

Is there a better way?

The other day, we met with an investor who has 40% of his portfolio in cash. He doesn’t like market valuations and has decided, he’ll put money to work if the market declines by 10%; then more money to work if it declines another 10%. We think this investment philosophy beats that of many. At least, he has taken chips off the table during the good times and has money to deploy. Before readers cry out: “There’s so much cash on the sidelines, this market must go up!”, I would like to caution that this investor is a rare exception of many investors I talk to – and I talk to retail investors, advisors, family offices, to name a few. The same person, by the way, told me he is at a loss on what to advise his friends, as he doesn’t want to encourage them to get into the markets given current valuations.

Indeed, this appears to be a market where just about every pessimist is fully invested. Because folks have been wrong so many times calling the market top, we believe many market bears are fully invested.

I think there’s a better way. The better way of investing is to take the long view. Sure it’s great to have one’s stock portfolio surge, but investing, in the opinion of yours truly, isn’t about gambling, but about asset allocation with humility. Passive investing is all right for certain things, but should not replace common sense. When the likely successor to Janet Yellen (we put our chips on Kevin Warsh) has complained that asset holders have disproportionally benefited from monetary policy, and that the focus has to shift, I think it’s but one indication to do a reality check on one’s portfolio, as headwinds to asset prices may well increase.

The short answer is that investors may well look at their portfolios more like pension funds or college endowments do. Except, well, many pension funds and college endowments have fallen into the same traps individual investors and advisors have. Let me rephrase: investors might want to invest according to a philosophy a well-run endowment might have. Let me just mention a few principles here. Here’s the investment allocation of an endowment of a private college – I’m not suggesting this specific allocation is the right one for any specific person or institution, but want to provide it as food for thought:

- 31% hedged strategies

- 27% equities

- 21% private equity

- 8% real assets

- 6% cash

- 5% fixed income

- 2% equity-like credit

Note that the equity holdings are less than 30%, not the 60% often touted in a “60/40” portfolio (with 40% referring to bonds). The number can be larger or smaller for any one investor, but I believe we should get away from the notion that one needs to have a large portion invested in equities. Endowments are long-term investors, yet don’t go to 100% equities; so why should a young investor be all in equities? By allocating a far smaller portion, you don’t need to lose sleep over asset bubbles. Instead, you can indeed rebalance or make gradual shifts.

Note the biggest bucket is “hedged strategies.” We have long advocated that investors need to look for uncorrelated returns. A long/short equity strategy or long/short currency strategy might generate such returns. Importantly, this bucket of alternatives is far higher than what many advisors choose. In an era of very expensive assets, we think this may be rather prudent. This doesn’t solve the issue of how to find the right hedged strategy – remember that those strategies will have under-performed the overall market. Important here is the investment process of the underlying ETF, mutual fund or whatever product one might want to consider.

Private equity is obviously not accessible to many investors. Relevant though is that there’s a big bucket allocated to investments where one expects a long-term return without seeing the daily price moves. Sometimes it’s good not to have tick-by-tick data. An individual investor might be able to replicate this by opening another account, selecting a few long-term ideas, then throwing away the key to the account for a few years. Well, one should still review the investments periodically, but the point being: it is okay to invest different portions of a portfolio according to different philosophies. Say, be a day trader for a small portion, but do hold strategic positions. Some of this can be achieved by intentionally mixing up the styles of different investment products. If not all of them perform well at the same time, that’s a good thing!

This particular portfolio has a small allocation to “equity-like credit”; we are not making a judgment whether this is too high or too low; the point again is that there’s a very broad allocation to different asset classes. Note, by the way, that ‘equity-like credit’ is likely to perform, well, like equities. Even with those assets added, the equity portion is still modest.

Not mentioned in this particular portfolio, as least not in the headline numbers, is an allocation to precious metals or commodities. Those who have followed us for some time know that we encourage investors to consider gold as a diversifier. We have often referred to gold as the “easiest” diversifier because it’s easier to understand than some exotic long/short strategy. In our analysis, the price of gold has had a near zero correlation to the S&P 500 since 1970; however, over shorter periods, correlations can be elevated. In our analysis, gold has done well in every bear market since 1971, with the notable exception of the bear market in the early 1980s when then Fed Chair Volcker raised interest rates rather substantially.

The point of all of this is not to suggest that investors need to add equity-linked credit or private equity to their portfolio. No, the point is that there’s more to investing than chasing high flying companies that promise to make Mars habitable.

You might have also noticed that I squeezed in the word “humility” in asset allocation above. Have some respect that things that go up can also go down. Having respect means that one doesn’t adjust one’s lifestyle (expenditures) as a reaction to rising asset prices. Investors can control expenses more so than income. So maybe we should be spending far more time talking about how we spend our money rather than how we invest it. But I digress…

Axel Merk

Merk Investments, Manager of the Merk Funds