Axel Merk, Merk Funds

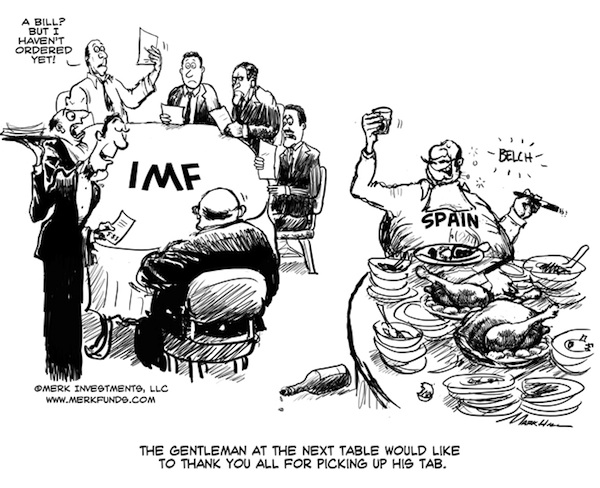

If running out of your own money wasn’t bad enough, policy makers are increasingly spending other peoples’ money to bail their country out. At the upcoming G-20 meeting, finance ministers from around the world will contemplate an increase to the resources of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). At stake for politicians is whether they can continue to do what they know best – to play politics. In contrast, at stake for investors may be whether currencies will retain their function as a store of value.

One of the major concerns is Spain’s regional government debt. Spain consists of 17 autonomous regions, whose total debt almost doubled in the past three years, due to economic recession and a housing market collapse. In many ways, Spain reflects a microcosm of how the Eurozone as a whole is structured:Let’s highlight Spain, as the country may be the key to understanding how dynamics may play out. Last November, Spaniards voted for change by electing conservative Prime Minister Rajoy, handing him an absolute majority in parliament, displacing the previous, socialist government. The election may cause former British Prime Minister Thatcher to change her view, that socialism is doomed to fail, as ultimately you run out of other people’s money. It doesn’t take a socialist to run out of money. In the case of Spain, if you run out of your own people’s money, there may always be other peoples’ money.

Spanish regions have the power to issue public debt. The central government has little ability to interfere with regional government spending and is prohibited by Spanish law to bailout regional governments.

While regions enjoy high autonomy on spending, the central government retains effective control over regional government revenue.

Spain has its own peripheral problems: the most indebted region, Catalonia, recorded 20.7% debt-to-regional-GDP ratio and 3.6% deficit-to-GDP ratio in 2011. Its 10-year bond yield recently breached 10%, far beyond the yield on 10-year Spanish government bonds, which yield around 6%. In 2011, the total debt of 17 regional governments rose to €140 billion, accounting for 13.1% of Spain’s GDP. This number is up from 6.7% by 2008.

Spanish law forbids the central government from rescuing regional governments (in much the same way that the Maastricht Treaty prohibits bailouts of EU countries). In practice, the central government appears to have implicitly helped Valencia, Spain’s 2nd most indebted region, with a €123 million loan repayment to Deutsche Bank.

More broadly known are Spain’s banking woes. Unlike much of Europe, a housing boom propelled much of Spain’s recent growth, causing Spain’s regional banks, in particular, to become overly exposed to the mortgage sector. Spain’s banks are very dependent on liquidity provided by the European Central Bank (ECB). The recent 3 year long-term refinancing operation (LTRO) by the ECB at first took pressure of the Spanish banking system, but has since been seen more critically, as Spain’s banks may be using the liquidity to buy Spanish government debt, thus increasing inter-dependency and potentially making nationalization of Spanish banks (read: the Spanish government taking on the obligations of its banks) more, rather than less likely.

To Read More CLICK HERE