Some influences on the stock market are casual, subtle or open to interpretation, but the catalyst behind the current stock market rally really shouldn’t be controversial. As far as stocks go, we have lived by QE. The only question now is, whether we will die without it.

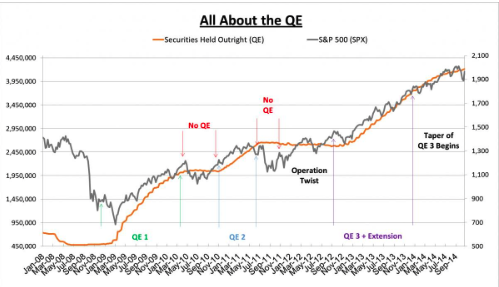

Since the financial crisis of 2008 stock prices have only risen when the Fed is either expanding its balance sheet, hinting that it will soon do so, or actively recycling assets to hold down long term interest rates. Absent any of these aggressive moves, stocks have shown a clear tendency to fall. Curiously, while most investors now believe that QE is in the past, and that the Fed will not even be hinting at a restart, few would argue that the current bull market is in danger. But a quick look at how much influence the Fed’s operations have had on market performance should send a chill down Wall Street. The Chart below should speak for itself:

Created by EPC using data from the Federal Reserve and Bloomberg

In August 2007, the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) target for the federal funds rate was 5.25%. Sixteen months later, with the financial crisis in full swing, the FOMC had lowered the target for the federal funds rate to nearly zero, thereby entering the unfamiliar territory of having to conduct monetary policy without the ability to cut rates further. Six years later, rates are still at zero. This has left the Fed’s capacity to buy assets on the open market (now known as Quantitative Easing – QE) as their principle policy tool.

The day after the Fed announced the end of QE 3, Paul Richards, the head of FX for UBS said on CNBC that he is “so bullish on stocks that it hurts.” One wonders if he had ever seen a chart like the one produced for this article. But Mr. Richards is not far off from the vast majority of U.S. stock analysts who see clear sailing ahead.

The day after the Fed announced the end of QE 3, Paul Richards, the head of FX for UBS said on CNBC that he is “so bullish on stocks that it hurts.” One wonders if he had ever seen a chart like the one produced for this article. But Mr. Richards is not far off from the vast majority of U.S. stock analysts who see clear sailing ahead.

In order to stop the markets from crashing further in the Fall of 2008, the Fed announced a plan to purchase $600 billion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and agency debt. When first announced, the plan faced some political resistance even though most thought it would be a one shot deal. But when the opening salvo wasn’t enough to push stocks back up, on March 18, 2009, the Fed announced a major expansion of the program with additional purchases of $750 billion of agency MBS and $300 billion in Treasuries. That got the market’s attention.

Between March 6, 2009, when the S&P put in its low watermark, and March 2010, when this program (which would become known as QE1) came to an end, the Fed had expanded its balance sheet by $1.43trillion, or 247%. Over that time, the S&P 500 put in a rally of 71%, rising from a low of 683 to 1169 at the end of March 2010.

But when the dust settled, bad things started happening. From April to November 2010, QE was on hiatus, and the Fed’s balance sheet expanded by just 1.5%. In this environment, stocks fared quite poorly. From the end of QE1 to August 2010, stocks declined by about 11%, the first correction since the market began rallying in 2009. As the markets panicked, the Fed came to the rescue. On August 27 2010, at an eagerly anticipated speech at the Fed’s annual Jackson Hole Wyoming retreat, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke strongly hinted that he was ready to launch another round of QE.

As it turns out, just a little tease was enough. The markets immediately started rallying, notching an approximate 18% gain in the final five months of 2010. The formal launch of QE2 occurred on November 3, 2010 when the Fed laid out a plan to purchase another $600 billion of mostly long-dated Treasury bonds. Like the first QE program, it was born with an expiration date (June 2011). By the time the program ran its course, the Fed’ balance sheet had swelled by 29.4% to $2.64 trillion, and the S&P 500 had rallied about 25% from its August 2010 lows. Fairly neat correlation.

But then the entire movie started again. When QE2 became a thing of the past in July 2011, markets turned south. With no QE wind at the back of Wall Street’s sails, and no hints that it would return soon, the S&P 500 put in a wicked 16% sell-off between July and August 19. A decent September rally soon petered out and by the end of September stocks were once again approaching their August lows.

Cut to Ben Bernanke charging on his cavalry horse, bugle firmly in hand. However, the Fed had become wary of falling into a predictable pattern of launching a fresh round of QE every time the market stumbled. So, on September 21, 2011, he announced the implementation of “Operation Twist,” which authorized the Fed to purchase $400 billion of Treasury bonds with maturities from 6 to 30 years and to sell bonds with maturities less than 3 years, thereby extending the average maturity of the Fed’s portfolio. By buying “on the long end of the curve” the plan hoped to push down long-term interest rates, thereby more directly stimulating mortgage origination and consumer and business lending. It was hoped that Twist would offer the benefits of QE without actually expanding the Fed’s balance sheet. A rose by another name could perhaps smell as sweet. And like the earlier QE plans, Twist was announced as a finite program with an expiration date.

Once again the markets responded, rallying about 25% from the end of September 2011 to the end of April 2012. But when Operation Twist stopped twisting, another sell-off predictably ensued. From April 27, 2012 to June 1, 2012, the S&P dropped 9%. So on June 20, 2012 the Fed extended Twist to the end of 2012, which would include an additional $267 billion of short term/long term debt swaps. From the time of the Twist extension announcement to September 14, 2012, the S&P 500 gained back more than the 10% it had lost. But towards the end of September the rally slowed and another fall threatened.

At this point I believe the Fed finally understood: No stimulus, no rally. And given that the surging stock market was a key element in creating the wealth effects that the Fed believed was essential to economic growth, they instituted a policy that would ensure market gains on an ongoing basis.

On September 13, 2012, the Fed announced a third round of QE which provided for an open-ended commitment to purchase $40 billion agency mortgage-backed securities per month. This unlimited QE eliminated the need for embarrassing re-launches every time the markets or the economy stalled. But the $40 billion monthly rate was apparently not enough to move stocks. From the time of the announcement to the end of 2012, the S&P declined about 2.3%. So then on December 12, 2012 the Fed voted to more than double the size of QE3 by authorizing monthly purchase of up to $45 billion of longer-term Treasury debt, on top of the mortgage debt they were already buying. The rest is history.

The past 18 months has seen lackluster economic performance, a deteriorating geo-political landscape, and, somewhat incongruously, a nearly relentless stock market rally. From the time QE3 was announced, until the program was officially wound down this month, the S&P 500 surged 36%. But the rally was expensive. During that time the Fed’s balance sheet of securities held outright, expanded by an astounding 63% to $4.2 trillion.

On December 18, 2013 the Fed announced the “Taper,” a regular reduction of QE3 at a rate of $10 billion every six weeks. On October 29, 2014, the Fed made good on its initial timeline and officially wound down the program.

Although the rally in stocks continued during the taper of 2014 the rate of increase slowed along with the rate of balance sheet expansion. Full throttled $85 billion per month QE persisted from September 2012 to December 2013. During that time, stocks rallied about 26%, and the Fed’s balance sheet grew by 45% to $3.7 trillion. Since the taper began, however, the Fed’s balance sheet has grown just 12% (through October 22, 2014), with the S&P 500 virtually matching that with a 12% increase. As the chart above clearly demonstrates, stocks have hidden the rising wave of Fed assets like a world class surfer on Hawaii’s North Shore. The big question now should be what happens now that the age of QE is apparently over, and the surf is no longer up?

The day after the Fed announced the end of QE 3, Paul Richards, the head of FX for UBS said on CNBC that he is “so bullish on stocks that it hurts.” One wonders if he had ever seen a chart like the one produced for this article. But Mr. Richards is not far off from the vast majority of U.S. stock analysts who see clear sailing ahead.

The day after the Fed announced the end of QE 3, Paul Richards, the head of FX for UBS said on CNBC that he is “so bullish on stocks that it hurts.” One wonders if he had ever seen a chart like the one produced for this article. But Mr. Richards is not far off from the vast majority of U.S. stock analysts who see clear sailing ahead.To reach that conclusion, one must completely ignore not only the role QE played in driving up stock prices, but discount any negative effects that a reduction of the Fed’s balance sheet could create. Most economists recognize that to normalize policy the Fed must reduce the amount of securities it holds. This will be an environment that we have never encountered. Logical analysis should lead you to believe that stocks would not fare well. But logic is not welcome on Wall Street.

The bottom line is that stocks should be expected to fall without QE. But this does not mean I predict a crash in stocks. I simply expect, as no one else seems to, that the Fed will go back to the well as soon as the markets scream loud enough for support. At that point, it should become clear to everyone that there is no exit from the era of QE and that there is nothing normal or organic about the current rally. At that point, the asset classes that have been ignored and ridiculed should have their day in the sun.